t the centre of The Virgin Suicides, Sofia Coppola’s dreamy yet devastating adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’s acclaimed 1993 novel, is an unsolved mystery of the most troubling kind, a puzzle that will never be completed. The questions asked by those in the film, and by us the viewers, will never be fully answered. An attempt to figure out the hows and whys will only ever be that, an attempt. It’s what’s left behind when someone kills themselves, a fog of painful unsureness, a feeling that I filed away as other when I was 16, watching it for the first of many times. As is the case for many teens, the idea had briefly entered my mind at certain low points, but it still felt distant, like looking at something through a camera that isn’t in focus.

Twenty years later, my experience of suicide, and, in turn, the film itself, has changed. Last year, a family member and a close friend both killed themselves, in the space of about six months, forcing an otherworldly concept into grim reality, a difficult confrontation most of us don’t expect to ever have. As I watched the film again, I found a new, deeper understanding of what Coppola herself described as “the extraordinary power of the unfathomable”, of how not knowing the answer to a question of such staggering gravity can haunt you, a grip that may loosen over time but will remain nonetheless.

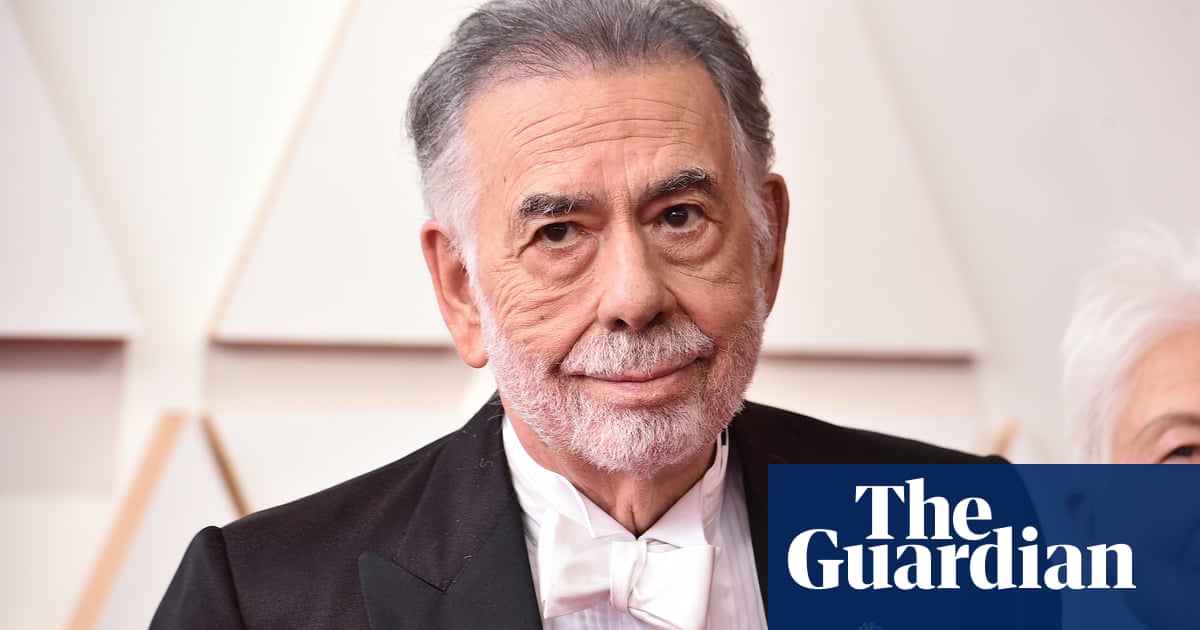

In an industry overrun with nepotism, there was every reason to wince at the film’s arrival at Cannes in 1999 (a year before its release): the first film from Francis Ford Coppola’s daughter, co-produced by him and starring actors he had worked with. The last we had seen of Sofia was in The Godfather Part III, disastrously miscast in what turned out to be a miserable experience for all of us, especially for her. It pushed her away from acting, something she was never that interested in anyway, and years later, with great help, she moved behind the camera, where she has remained ever since.

Shuddering memories of Boxing Helena (David Lynch’s 19-year-old daughter Jennifer’s laughable debut), Paris Can Wait (Francis Ford Coppola’s wife Eleanor’s indulgent and uninteresting attempt at directing) and pretty much anything written by John Landis’s son Max have shown us the dangers of Hollywood over-assistance, a heavy-handed ushering of vanity projects that make it to the screen for all the wrong reasons, home movies that should have stayed at home. But with The Virgin Suicides, Sofia Coppola emerged from her father’s shadow with purpose, the work of a film-maker who wasn’t just doing it because she could but rather because she should, an innate ability that would have pierced through with or without the help of an Oscar-winning parent.

Set in 70s Michigan, in a suburbia that’s both recognisably banal and at times ethereal, The Virgin Suicides opens with a suicide attempt. Cecilia Lisbon, the youngest daughter of five, has tried to kill herself, an act that leads to concern and confusion from those in the community. “You’re not even old enough to know how bad life gets,” she’s ignorantly told. “Obviously, doctor, you’ve never been a 13-year-old girl,” she smartly replies. It’s the beginning of the end, as told to us by an unseen narrator, the grownup version of a neighbourhood boy from the time, part of a quartet of curious locals whose obsession with the Lisbon girls has continued long after their deaths.

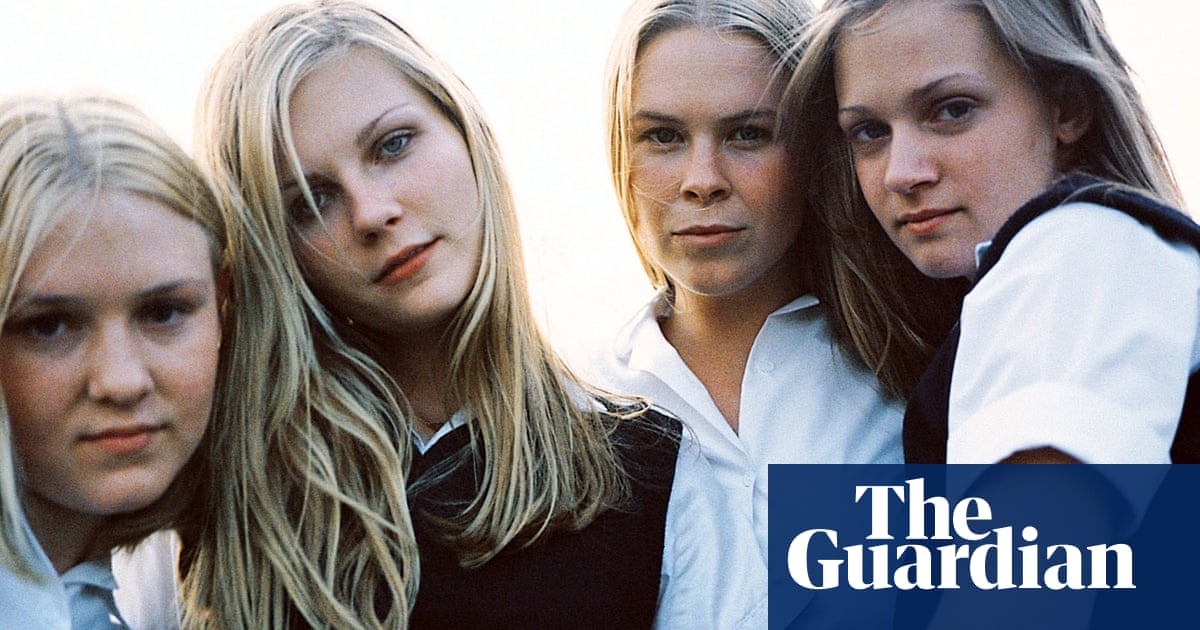

Coppola keeps us at a distance from the sisters (played by Kirsten Dunst, AJ Cook, Leslie Hayman, Chelse Swain and Hanna R Hall), offering us brief anecdotes and scrappy clues so that we, like the boys, are left with only random pieces of the puzzle. The parents, played by Kathleen Turner and James Woods, are strict but not unloving, religious but not extremist, clueless but not in a way that isn’t relatable and so while speculation from gossiping neighbours places responsibility for what happens solely at their feet, we know it’s not that simple; it never is. The rush of unfamiliar, unwieldy emotions that come for us all during adolescence are too easily minimised by those who have already gone through it, as if the bigger picture they now see should be visible to all, and so, for me, at the core of the film is a collection of muffled screams. The first real scream we hear is when Cecilia kills herself, soon into the film, not long after her first attempt. We’re shown how those who knew her and those who didn’t all struggle with what to do, what to say, how to react, who to blame, an impossible situation that arrives without precedent.

Coppola notably shows us no sign that the grief experienced by the surviving sisters is taken into account, is treated with the severity it deserves, and so life goes on as normal to those on the outside. But there’s a wound that lingers. When the girls are forced to stay inside as punishment, after Dunst’s Lux spends the night with a boy, Trip Fontaine (played by a 21-year-old Josh Hartnett at the height of his heartthrob years), we see the toll it starts to take. Their imprisonment is to them a clear sign that they’re neither understood nor respected. “We’re suffocating,” Lux says to her mother in a telling fragment of a scene near the end. “You’re safe here,” she replies. “I can’t breathe in here,” Lux answers.

The dreamy aesthetic and Air’s transcendent, perfectly matched score led some to dismiss the film as a mere mood piece, of style over substance, but it’s too grounded, too rich in detail to fall into that overused categorisation. We see that in a flash forward to an older Trip, whose teen bravado has faded into pathetic delusion, and we feel it in the finale as the boys discover the girls’ bodies, while dreaming of the “impossible excursions” they were planning to take. It remains Coppola’s best film, in my opinion, because of this, because the emotions that accompany the atmosphere haunt with equal force.

It’s as much about those who leave us as it is about those who are left behind, lumbered with what Coppola refers to as an “oddly shaped emptiness”, a misty, unfocused form of grief that I now know firsthand. The final, mournful piece of narration expresses sadness over the loss but also a stinging sense of regret. If the boys had just called that little bit louder, if they had just arrived that little bit sooner, maybe things might have been different. They’re agonising questions that we, as those who are still here, will always ask ourselves, knowing that the answers will for ever remain a mystery.

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email: jo@samaritans.org or jo@samaritans.ie. In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255. In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org