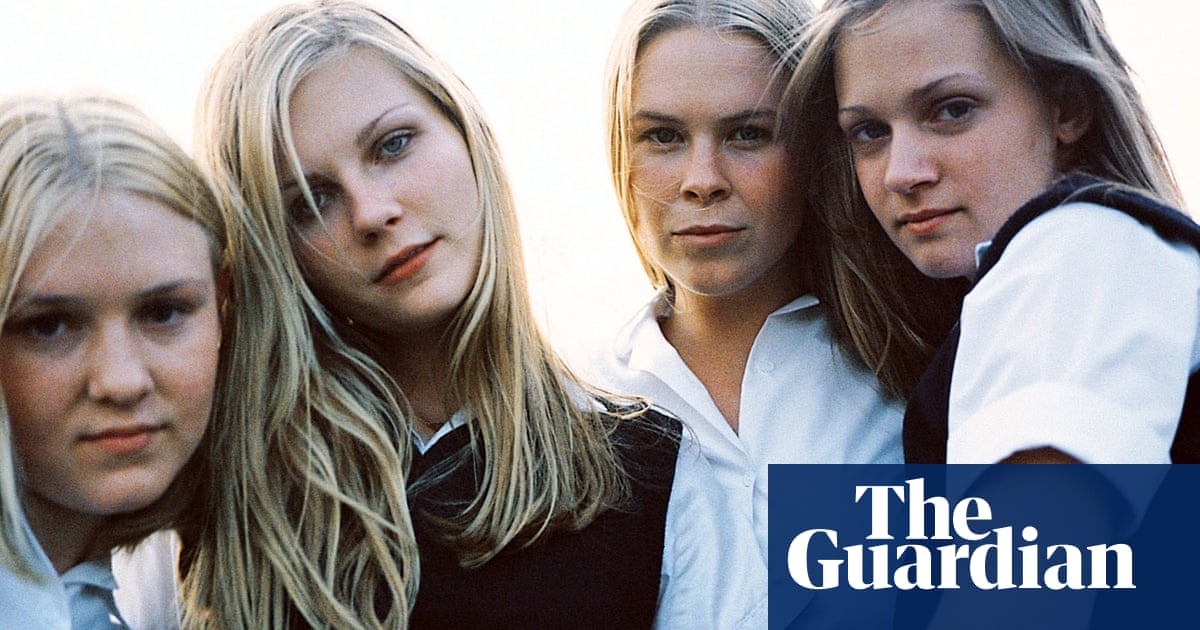

The Virgin Suicides was published in 1993, the year Bill Clinton became president, the first Beanie Baby went on sale, and Cern released the world wide web source code into the public domain. It was also the year I was born. Fifteen years later, I saw Sofia Coppola’s film adaptation, and my instant messenger avatar became Kirsten Dunst, picking petals from a daisy, stained pink by sunset. Along with many girls in my high school, I wasted hours with digital cameras trying to capture the same dreamy aesthetic as the movie. We held bougainvillaea flowers and posed by stinking suburban lakes, hiding behind our hair, always disappointed by the results that turned out too bright, too childlike, too true.

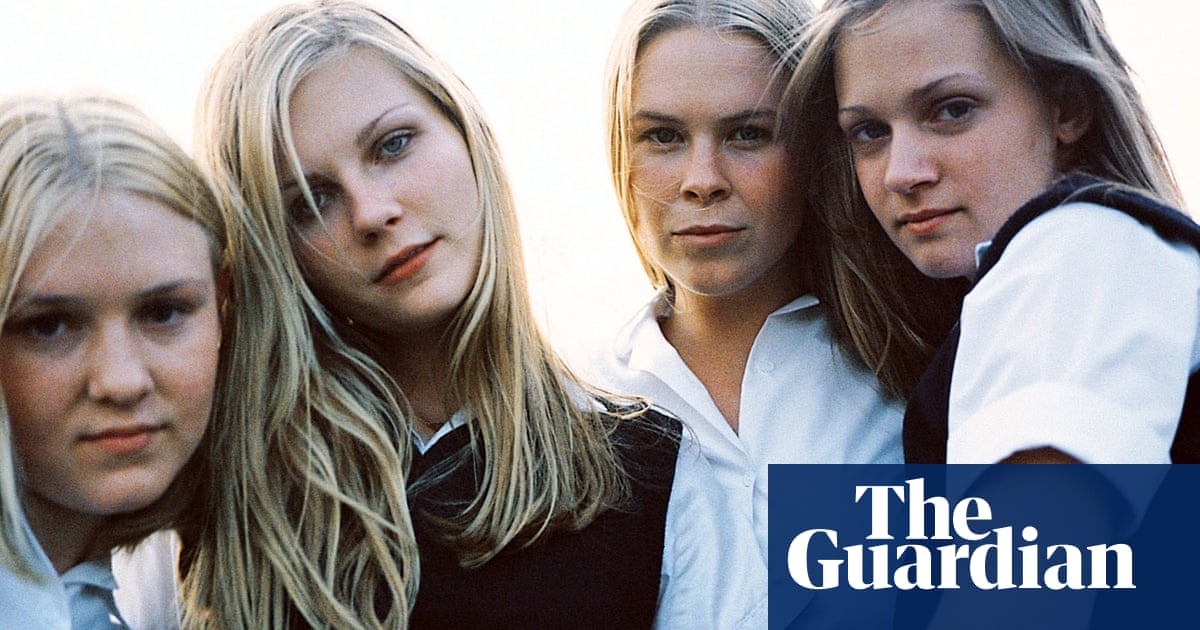

The book soon got passed around the more committed, easily-influenced-by-Tumblr girls. Although I grew up in Orlando, and the novel is set in the suburbs of mid-70s Detroit, where I have never been, the landscape felt so intensely familiar that I read it for the first time as though remembering it. I fell even more deeply in love with the five Lisbon sisters – blonde, long-haired and beloved by the boys across the street, who narrate the novel from a distance. I was as quick as the boys to believe the girls were angels: beautiful, tragically cool. I didn’t realise then, but I shared a viewpoint, not with the sisters as I hoped, but with the boys who never got near them. Dumb with longing, we all completely missed the point.

The novel is true to its title. First comes the suicide of 13-year-old Cecilia, the “weir”’ sister who always wears a wedding dress and high-tops she keeps clean with a toothbrush, who writes a diary and cares deeply about the fate of an elm tree in the family’s front yard. Over the course of the next 13 months, as her parents and sisters deal with their grief, they become increasingly isolated, or incarcerated by the neighbourhood’s silent judgment, depending on who the boys talk to (“That girl didn’t want to die. She just wanted out of that house.” “She wanted out of that decorating scheme”).

There are a few attempts to break through the family’s stony silence, giving the novel its propulsive movements; the priest visits, then the high school heart-throb, the local news anchor. But all give up, or get spooked, abandoning the sisters to their loneliness, returning across the street to carefully observe the slow decay of the house from afar, for the purpose of gossip, or, in the boys’ case, for love. The time lines entangle in the way of a true-crime documentary; we get talking head interviews with different characters, now decades past the tragedy and living in a new 1990s America of rundown rehab centres, bus station coffee shops, botanical gardens that have turned, unfunded and untended, to mud. In a brilliant inversion of conventional structure, the peripheral characters, the neighbourhood chorus, are the only voices we hear. Everyone remembers the Lisbon sisters and has their own version of the tragic events, their own theory (the girls’ serotonin levels were low, it was a suicide pact built in satanism).

The novel may be bleak, but it is frequently hilarious and never cruel; it skewers the boys, with their hard-ons and their helplessness, but it takes their love for the sisters seriously. Equally, it is honest about the girls – they, too, are obsessive, needy, a little gross. Their beauty is constantly commented upon, but either wildly overblown or quickly contradicted; the girls have too many teeth, bleached moustaches, dirty feet. By the end of the book, their house emits a smell that is “partly bad breath, cheese, milk, tongue film, but also the singed smell of drilled teeth”. The boys’ idea, that the girls were “really women in disguise, that they understood love and even death”, is shown to be a misunderstanding of what the girls want, hinted to be not dissimilar from the boys’ own desires: to be loved, to be understood, to be told the truth and not just told to be happy. Their jointly inherited, carefully groomed suburban Earth is under threat; they hear Detroit burning beyond the neat lines of their neighbourhood lawns, their trees are succumbing to Dutch elm disease, and fish fly season rears its head once a year, covering their homes in a thick mesh of husks that smell “faintly of carp”. The momentum of the novel comes not only from the girls’ tragedy, but from the neighbourhood’s suspected demise; everyone is paranoid, as though sensing the American dream is already dead.

The book’s author, Jeffrey Eugenides, has said that though he only realised it many years later, he wrote the novel to reflect the experience of growing up in a declining Detroit. I return to it so often because it tells a particularly American truth, recognisable to anyone who was raised there, and one that has kept me writing, and rewriting, my own novel, Brutes, wanting to articulate this truth for myself. For me, growing up in a land of sunshine only made the shadows more exaggerated, easier to see when looking back. Orlando is a relatively new city; since Disney opened its doors in 1971 and proclaimed itself the happiest place on Earth, the population has tripled. My family moved there a month after 9/11, into an America of pumped-up patriotism, suspicion and an optimism that verged on desperation.

Construction was everywhere in Orlando in the early 2000s, new and shiny suburbs radiating across hurriedly drained swampland. Banks built the city’s first skyscrapers along the highway, an advertisement for a show-off economy that reflected the neon-pink glory of Florida sunsets every night. Then came the financial crash of 2008. Wages stagnated in the theme parks and job cuts began. Cheap pastel-coloured hotels that had hoped to become tourist traps instead became makeshift public housing in a city of escalating rents. My friends and I walked around eerily empty malls, store fronts dark with curling closing-down banners, oldies radio stations echoing loudly against the unscuffed floors. The skyscrapers that had been built in such optimism stayed empty, glass towers that only served to reflect light on to the highway, temporarily blinding the drivers who sat in the clogged traffic of a city with no public transport. All this promise was built on the least sturdy land, and the swamp proved less pliable than predicted; sinkholes opened up frequently, hurricanes wiped out power for weeks on end, and alligators inhabited every suburban lake, posing a danger to dogs and small children.

I have reread The Virgin Suicides dozens of times in my life, returning to it with the same obsessive tendency as the narrators, once boys and now men, with “thinning hair and soft bellies”, still calling to the dead girls as though they alone hold the answer to the disappointment of the men’s days, where they are “happier with dreams than wives”. When I first read the book, I felt sure that the girls could have been saved, if they had only realised how much the boys loved them, or, at least, loved looking at them. But when I read the book now, 30 years after it was published, I read it as a tragedy, one that the men only realise too late, and never wholly; that what the girls wanted was not idolatry but to be seen as they were. The novel expertly travels across swathes of time, and it hints that things do not necessarily get better or worse but only more true; that the past cannot be preserved in the idealised light of adolescence, and that if we looked closely, we could see none of it was ever as pretty as we once thought. First loves look like strangers, first kisses meant more than the later ones only because for a time they were the only ones we had to remember. The Virgin Suicides is an elegy to the power of first feelings, including betrayal, when we grew old enough to no longer believe in the simple stories our parents told us about the world they built. A world that turned out to be as insecure as a teenage girl looking in the mirror, as a city built on a swamp.

Brutes by Dizz Tate will be published by Faber (£14.99) on 2 February. To support the Guardian and Observer, order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.