n 1986, a 69-year-old Miles Axe Copeland Jr gave a memorable interview to Rolling Stone magazine. His three sons were all music industry powerhouses – Stewart played drums in the Police, Miles III was their manager and Ian their booking agent – and Miles himself had been a jazz trumpet-player in his youth. But the interview wasn’t about music. The subject was his days as the CIA’s man in the Middle East between 1947 and 1957, during which time he dined with President Nasser of Egypt, partied with the Soviet spy Kim Philby and, as a pioneer of “dirty tricks”, played a part in removing the leaders of Syria and Iran. Inconveniently for his youngest son, he concluded the interview by implying that the Police were a psy-ops outfit who played shows to “70,000 young minds open to whatever the Police decide to put into them”.

“You know it got old Sting on a bad day,” Stewart says, tickled by the memory. “He knew my father very well, and he regrets it now but he took adversely the suggestion that he was a CIA pawn.”

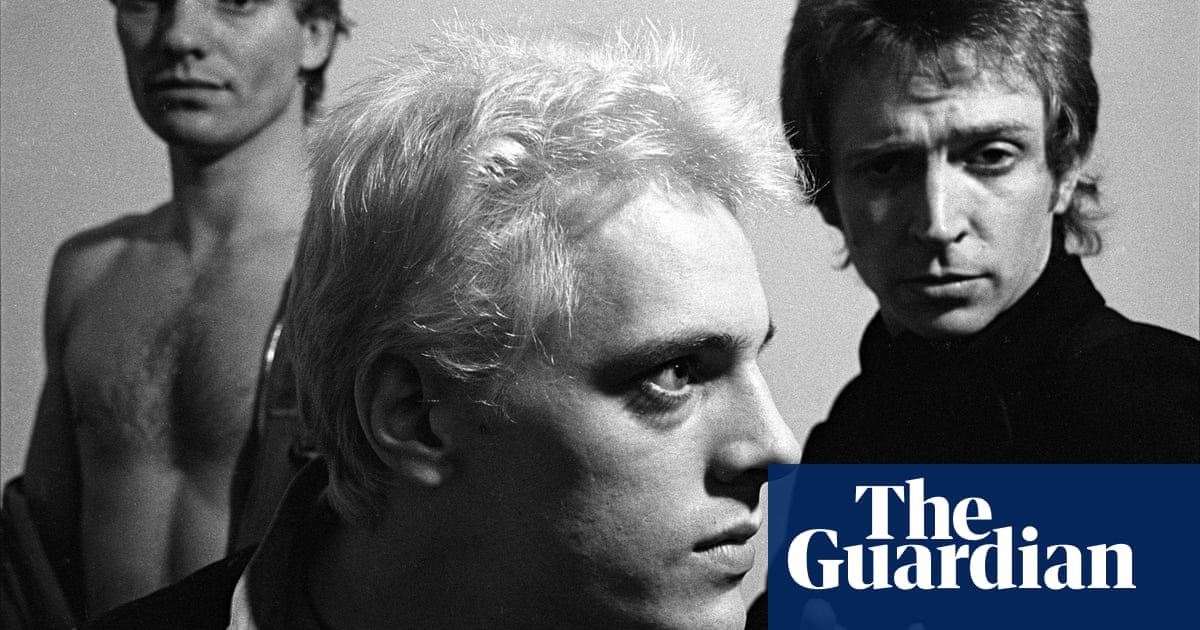

Stewart calls his dad, who died in 1991, “something of a wag – a bomb-thrower”. He was the kind of man the BBC would book for a late-night talk show to exasperate Tony Benn with an unapologetic defence of US realpolitik: “There were those under whose skin he could successfully crawl.” On a video call from his home in California, where he now writes operas after two decades of post-Police film scoring, Stewart appears to be his father’s son. Surrounded by books and an exotic array of musical instruments, he’s a natural storyteller with a love of funny voices, florid vocabulary and wry asides, all delivered at high velocity and top volume as he bobs and weaves before the camera like a debonair boxer. He tried to turn his father’s CIA years into a movie, but investors wanted to emphasise the Police connection and he didn’t, so it has mutated into a very entertaining nine-part podcast for Audible.

Miles Copeland Jr was born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1916. During the second world war he was a US agent stationed in London, where he was involved in the disinformation campaign preceding D-day, and married a Scottish intelligence agent called Lorraine Adie, who later became an archaeologist. When the war ended, Miles became one of the CIA’s first recruits and was posted to Syria. Though born in Virginia in 1952, the youngest of four, Stewart spent his entire childhood and adolescence in Beirut and Cairo, and attributes his drumming style to his immersion in Arabic rhythms. “We felt underprivileged,” he says, “like we were missing out on this unattainable land of perfection where everything was shiny and modern and cool. It wasn’t until we grew up that we realised, actually, the place that we lived had a lot of cultural advantages.”

After leaving the agency in 1957, Miles became a well-paid consultant and conservative journalist. Not until 1969, when he published his bestseller The Game of Nations: The Amorality of Power Politics, did Miles’s offspring finally discover what he’d been up to. His children had been as oblivious to his clandestine activities as he had to Kim Philby’s.

Were they never bothered by the fact that their father had lied to them? “He didn’t lie to us,” Stewart corrects me sharply. “He just didn’t tell us the whole story. But we never asked.”

And you never guessed?

“It may surprise you to know – and it surprises me to recall – that we didn’t think about it that much.”

Stewart thinks Miles would have disliked the title of My Dad the Spy (“He was kind of a snob in that regard – ‘spy’ was somehow déclassé”) but I don’t imagine he would have any other complaints. While many musicians have unresolved issues with their fathers, Stewart, whose teenage rebellion lasted “about 20 minutes”, doesn’t have a bad word to say about his. In the podcast’s dramatised recreations, actor Kerry Shale captures the sly southern charm that served Miles well as an agent and a parent. For a man who led a double life, he was a remarkably consistent character.

“Everything I learned at his knee in the family home was confirmed by the historians,” says Stewart. “Not only was his nature described exactly as I remember him – a very jocular, cheerful, witty, charming man – but also the stories.”

When The Game of Nations came out, Stewart was a college student in the US and the CIA’s reputation was mud due to a slew of ugly revelations. Nonetheless, he thought his dad’s old job was “cool” and has never revised that opinion. When he was in the Police, he says, it was never a major issue. “I think behind our backs people did write the Copeland brothers off as rightwing monsters, but I got on pretty well with everybody. Decades later I remember hanging out with Rage Against the Machine and Zack [de la Rocha] was looking at me pretty funny but the other guys were friendly. His main problem was that I played polo.”

Still, it must have been uncomfortable sometimes. In that 1986 interview Miles said: “My complaint has been that the CIA isn’t overthrowing enough anti-American governments or assassinating enough anti-American leaders, but I guess I’m getting old.” Given that the Police were about to headline Amnesty International’s Conspiracy of Hope tour, wasn’t that a bit awkward?

“Oh, that’s right, my father’s gag,” Stewart laughs before stopping himself. “Now I can sympathise with people from those countries who would not be amused by my father’s puckish sense of humour and would have every right to look askance at this messing with the destiny of their nations.”

The tone of the podcast, too, oscillates between playful and earnest. The first few episodes present Miles as an Ian Fleming character in a Graham Greene world, buccaneering his way through the Levant. Only later does Stewart confront the geopolitical implications and talk to Middle Eastern historians who blame his father for what later unfolded in Iran: no coup against prime minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in 1953, no tyrannical Shah, no Islamic revolution in 1979. Stewart hotly disagrees.

“Guys, 70 years have gone by! The current regime of Iran was not chosen by the CIA. It’s what happened when the Iranians chose their system of governance. For right or wrong, it’s theirs.”

But does he really think he can be impartial about his father’s role in the region?

“When it comes to my father, you’re right, I cannot be objective. But I am interested in that region. I’d say that 80 million Iranians are more in charge of their own country than three Americans.”

Stewart describes his father, approvingly, as Machiavellian. Unlike his intellectual mentor James Burnham, Miles was less a fanatical cold warrior than a good soldier who took great pride, and no little pleasure, in serving US interests by any means necessary. A good agent, he maintained, was amoral. So, too, despite the lofty public rhetoric, was US foreign policy.

“My father’s view was that democracy was like two wolves and a sheep voting on what’s for dinner,” says Stewart, “and indeed in the Arab world it’s very much like that. My father wasn’t in the business of exporting democracy. He was in the business of getting the oil to the west by hook or by crook.”

Miles thought the CIA went downhill after Dwight Eisenhower left the White House. “Although engaged in the same skulduggery it was much less successful,” says Stewart. “Kennedy, Nixon, they all fucked it up. Kennedy didn’t understand the military jargon. He didn’t understand that ‘a fair possibility of success’ means ‘you’re fucked’.” Things only got worse. “Instead of my father going in there and pulling some strings – a little bit of bribery here, a little bit of disinformation there, and hey, we’ve got a new guy in there who’s much more copacetic with our oil needs – decades later they went in and killed 100,000 Iraqis. That’s. Fucked. Up.”

Of course, not everybody will condemn a war while absolving a coup, or make distinctions between different eras of CIA meddling. My Dad the Spy features the voices of historians, including Iranians and Syrians, who cannot forgive Miles Copeland Jr’s machinations and you can hear the filial loyalty in Stewart’s voice when he pushes back. Miles apparently had no regrets and Stewart has none on his behalf. Can he see his father’s legacy clearly? Can any loving son or daughter? I’m not sure. Our family histories are complicated enough without having to factor in the byzantine intricacies of the cold war.

Before he goes, Stewart says he hopes that Philby’s children will see this interview and get back in touch. Having been childhood friends in Beirut until their father’s defection to the USSR in 1963, he’s a little hurt that one of them ghosted him a few years ago. Then again, he adds, “I appreciate that for that family it was not a matter of amusement as it is for me.”

• My Dad the Spy, an Audible Original Podcast, is available to download from Audible.co.uk