My brother Ian threw the best parties. After our show [playing with Curved Air] in Leicester and a two-hour drive, when we get back to slumbering Mayfair in the dead of night we can hear the revelry from blocks away. Sonja [Kristina, Curved Air singer] and I run up the stairs to the penthouse apartment and find bedlam swinging from the chandeliers. Ian has excelled himself. His natural engaging effervescence, instinct for the perfect music and rousing party shaman-ship has lit up a crowd of the strangest-looking kids leaping around our gothic manse.

The music was raucous through Ian’s million-watt stereo speakers and every note said BURN IT ALL DOWN! I’m not sure that anyone was pogoing yet but with all the gilded furniture pushed to the side, the grand drawing room was heaving under the stomping feet of a tribe of what came to be known as punks. Torn black suits and spiky hair with a kind of vertical dance motion. Not spaced out but Here, Now and In Your Face. Joyful rage!

Shortly before our arrival the party had been crashed by Sex Pistols’ Paul Cook and Glen Matlock with their scenic crew, fresh from shocking the nation on TV. Ian no doubt had the grooviest of London music business movers all dancing suavely to Average White Band and Chic but then these wild-looking strangers arrived, with records of their own to play. Ian was a single-deck proto-DJ. The jagged segues while he dropped the needle harshly to check out the records that the punks had brought were perfect for the jagged energy of the room. When he landed on Richard Hell’s Blank Generation the room exploded with frenzy.

And this was soooo not dance music as hitherto known. The kids were electric but there was a similar voltage of outrage from all of our fancy friends. The prog cognoscenti were coughing, spluttering and sulking on the perimeter. There were no triplets! Only two chords! That’s not singing, it’s shouting! But Ian’s got a connection with the dance floor. Everybody in show business is searching for the Next Big Thing and we were looking at it right there. The suits and the short hair were like a nightmare version of The Man that hippies were congenitally opposed to. The revenge of straight people returned as electrified zombies high on glue rather than pot! Those kids were an insult to everything that my band stood for, but dang! I felt like I was on their side.

Three days before our Mayfair bacchanalia Steve Jones had said “fuck” on national TV and the tabloids had erupted with glorious fury. The tide shifted and the next wave began to roll in. This time I’d be surfing on the front of the wave rather than swirling in the hippy suds on the back side. By the end of 1976 London was really lit up. Everyone could feel that cultural history was being made. Miles and I quickly saw an opportunity. We were inspired by the naive energy of these new bands and soon found ourselves immersed like sharks among minnows. For me, it was partly the DIY scale that drew me in. Old-school bands like Curved Air lived in towers, far removed from the levers that controlled our destiny. We were like mini oilwells for the record companies whose clients were Top 40 radio. We were their product, locked in our luxury cans. But now there were new clubs opening and one-off events happening, with an alternative information stream and new routes to notoriety. Open rebellion against the old order! I wanted a do-it-yourself band.

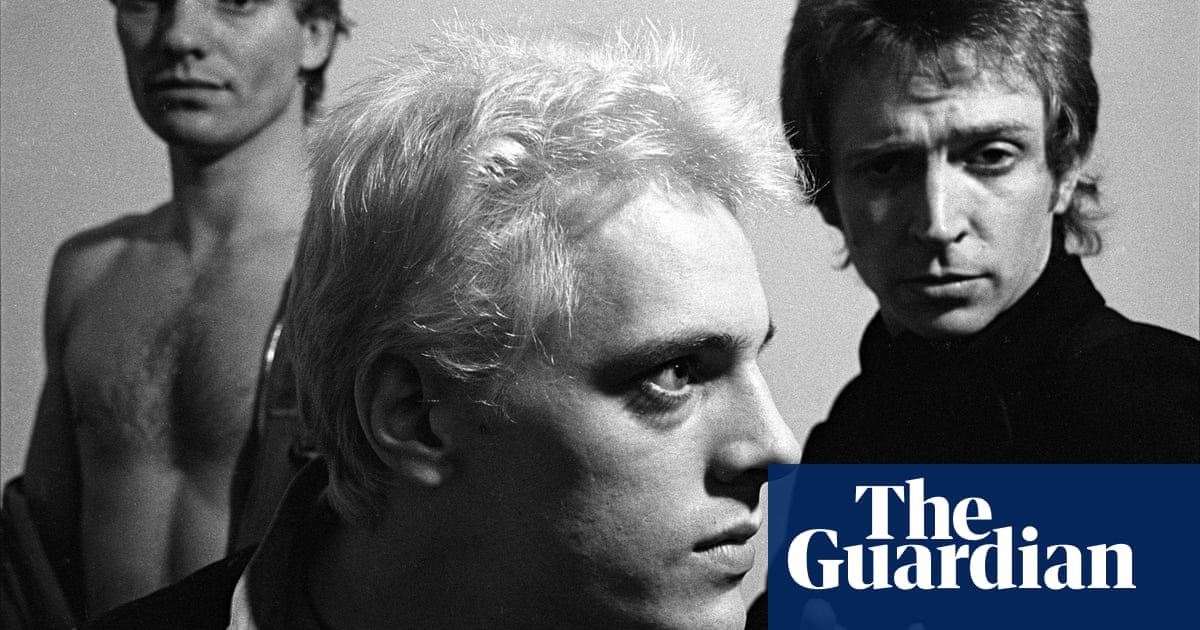

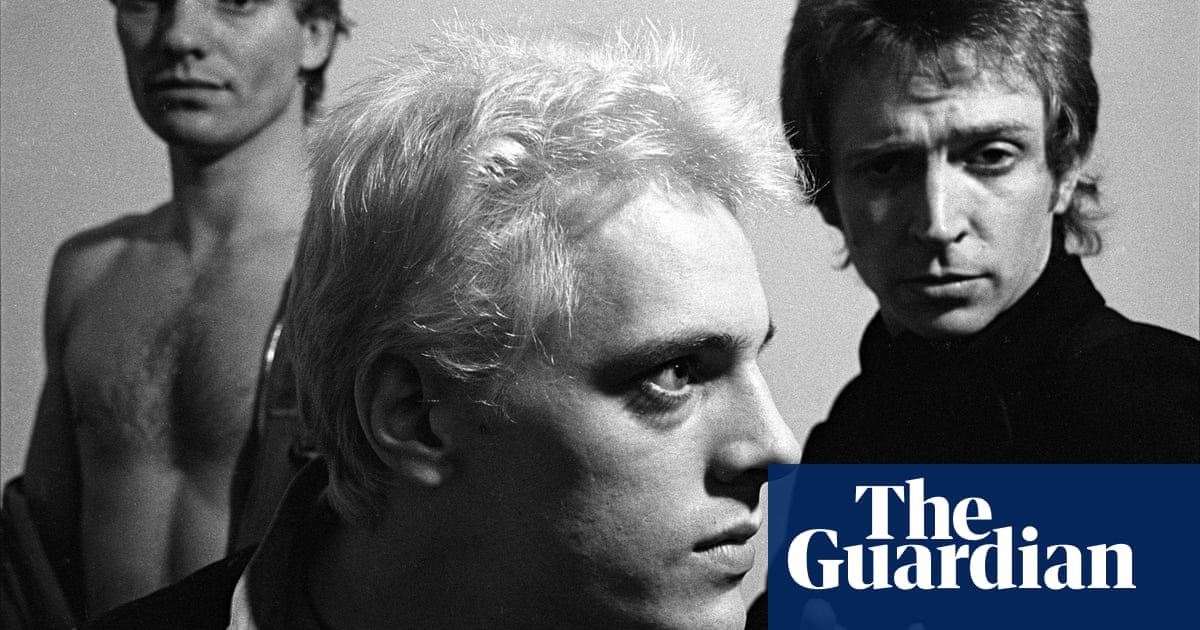

By now I knew every nut and bolt of how bands work and where every penny comes from and goes to. It had to be a trio because that’s how Jimi Hendrix and Cream did it. Blazing on my drums gets me breathing too hard for vocals, so either the guitarist or the bassist had to be the singer. I had a pretty utilitarian view of singing and placed more value on charisma than vocal excellence. Besides, in this new scene it was mostly yelling anyway.

I had to find two players, one of whom must take the mic while hammering his axe. Also in our clique was Paul Mulligan, my brother Ian’s old friend. They used to steal motorcycles together back in Beirut, where we had lived as diplo-brats in the nexus of Middle East intrigue. Actually, I imagine it was Ian who did the stealing and Paul who would fence the merchandise. But that was when they were kids. Paul was now a co-owner of a small airline, a man of means, and he loved to party. He collected people that were effervescent, charismatic … or useful. In the former category was his Corsican mate Henry Padovani (who only recently, after 30 years of friendship, told me that his name is spelt with a “y” rather than an “i”). He said he played guitar and did have an instrument. Right there he was more qualified than anyone else that I could find, but he couldn’t sing. But then there was a bass player that I knew of who could. That Lion King guy in that jazz band [Last Exit] up in Newcastle.

I was all excited to get his phone number from Phil Sutcliffe, the journalist who had taken me to the Last Exit show. Instead of sharing my excitement, though, Phil was immediately suspicious. My mistake was to start by gushing about the cool stuff happening in London. Stuff called punk. The temperature dropped 30 degrees. Anyone with a slot in the Old Order of the music business – which was any professional – regarded punks as barbarians at the gate. All that was sacred was under assault, and here was I, babbling on about luring the leader of Newcastle’s finest art band down into the swamp of Satan! Phil steadfastly refused to give me his number. Um … OK.

After hanging up and striding around the room in urgent circles I figured out a more persuasive tack for Phil. It was something along the lines of “Give me his fucking number!” But he didn’t pick up the phone, his girlfriend did. She brightly told me that Phil had gone out but, remembering how devoted he was to Curved Air, offered to help in any way she could. “Sting’s number? Hang on a tick.” I could hear her footsteps receding to find Phil’s phonebook while I held my breath. Then she was back, and I was scribbling down the number.

One minute later … “Keep talking …” said that husky voice that we all now know so well.

I had called him out of the blue and asked if he had any ambition to hit the big time down in London … without his band. In those two words “keep talking”, our relationship was defined for the next two years. I had to keep talking up our prospects so he could confidently pour his mojo into our combined mission rather than into all of the other options in the big city. I also learned right there that he was a free agent and open to suggestion. Excellent! He got an earful of my grandiose designs and convincing certitude but I was careful not to emphasise the punk thing. It was more about how we could use this new scene to get around the sclerotic music business empires and storm the walls.

Sting had a very northern suspicion of “the Big Time” and my do-it-yourself scheme appealed to his work ethic. We were not selling out to The Man! By the time he realised who we were selling out to (London critics) it was too late. The frog was boiled. He said he had been thinking of making a break for the big smoke. He took my number and said he would call me.

Which he did on Tuesday, 14 December in the year of our Lord 1976. He had just arrived from Newcastle with bass, wife Frances Tomelty, new baby Joe, and dog Turdy. They had come south to pursue her promising acting career and his few leads in music. One of which was me. On that day then, out of the blue he called me from a phone booth on the street downstairs and three minutes later was standing in our Mayfair apartment.

God knows what he thought of the vampire chic ambience of the place. I soon had Ian’s Ampeg bass in his hands, jumped behind my drums and set the controls for the heart of the cosmos. Dang! Two complete strangers but we were immediately in deep music dialogue throwing zingers and catching sparks; raging high and digging deep. I could throw any rhythmic curve ball and he could land right on it. He was coming up with bass lines that were a whole new world of groove. With all of that going on we had a pocket, a lock on each other’s pulse – which is the holy grail of all ensemble music. This mysterious stranger and I knew right away that we had something rare.

Later that night we went down to Covent Garden for the pre-opening night of the first dedicated punk club: the Roxy, and saw Billy Idol’s band Generation X rock the house. I dragged my new chum down there to show him the minnows that we, as gnarly sharks, could consume. We both knew that we were “real” musicians and in our shared arrogance knew that we could eat everybody’s lunch. Never mind for the moment the braying cacophony of this new scene’s primitive music, it was a wall that we could climb. A surge that we could ride. Worth getting a haircut for, Stingo?