onathan Meades is a sceptic. Not in the debased sense of someone who gullibly parrots the claims of shills and the deluded that global warming is a hoax, or that masks don’t mitigate the spread of respiratory viruses. Nor in the idly egotistical sense Meades himself identifies as “the English bents towards spiritual sloth and intellectual incuriosity, what we dignify as scepticism”. But in the fiery and ancient sense of scepticism: he is not just a man of little faith but an enemy of belief itself: a jeerer at creeds, a sneerer at doctrines of all flavours, metaphysical and otherwise.

He has too much sly wit, of course, to identify himself as such: “While it would be beguiling to appoint oneself part of that knowing cadre which lacks conviction,” he admits in the preface to this new collection of journalism and speeches, “I lack the conviction to do so.” He does not, like some celebrity pontificators, award himself a gold star for his ability to identify junk. He is too busy enjoying himself blowing raspberries. Meades sees faith everywhere, and loudly despises it everywhere. Not just in the screeds of terrorists or Catholics, about which he is entertaining enough (in one piece, he refers lightly to “the Church’s strong suit, paedophilia”), but also in politics.

Nationalism, for one thing. “Like all causes, all denominations, all churches, all movements, nationalism shouts about its muscle and potency yet reveals its frailty by demanding statutory protection against alleged libels,” Meades wrote in 2006. The coming of Brexit did not moderate this view. “The nationalist urge to leave was a form of faith,” he observed in 2019. “A faith is autonomous. A faith requires no empirical proof ... Taking Back Control was a euphemism for the Balkanisation of Britain, for atomisation, for communitarianism based in ethnicity, class, place, faith. A willing apartheid where the other is to be mistrusted – just like in the Golden Age when we drowned the folk in the next valley because their word for haystack was different from ours.”

Dr Bruce Banner used to warn: “You won’t like me when I’m angry”, but the aficionado of Meades is always hoping for the inevitable transformation, the dandyish Hulk rampage. One of the foremost prose stylists of his age in any register, Meades has an especial ear for the brutal music of invective. He is surely one of the planet’s best haters. The present prime minister, unsurprisingly, has proved a potent inspiration. “Boris Johnson’s lovable maverick shtick has been to dissemble himself beneath a mantle of suet, to pretend to inarticulacy, to oik about as the People’s Primate, to wear a ten-year-old’s hairdo, to laugh it off – no matter what it is, no matter how grave it may be – and to display charm learned at a charm school with duff tutors,” he writes. “This construct is going on threadbare. If one devotes such energy to a simulacrum of oafishness one becomes an oaf.” Johnson is, he joyously adds, “a blubbery pink peculator” who is said to have enjoyed “an assisted siesta in Shoreditch”. In that phrase “assisted siesta” we witness the pure poetry of vituperation.

A soft target in more ways than one, Johnson is joined in this volume by other bovines more widely held sacred. George Orwell is a “mediocre novelist” and his mad writing advice has had a chilling effect on prose style. (“Plain speaking, like plain food, is a puritan virtue and thus no virtue at all,” Meades pronounces.) Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, the urinal sniggeringly exhibited in a gallery, “was a dull jest then and it remains a dull jest, but it has for a century been treated with reverence by morons”.

There are certainly enough morons to go round, all spaffing the faddish lingo Meades is so expert at dismantling, for instance the idea in urban-regeneration circles that neighbourhoods improve when “creatives” move in. “‘Creatives’ in this context is a grossly flattering epithet for brainstormtroops, multiplatform contortionists, important synergy gurus nuking an outmoded logo from the face of a polo shirt,” Meades notices. “What it does not signify are actual makers, writers and artists.” Do not meanwhile get him started on “curators” (“achingly hip neophiliacs”) or “sustainability” (“Life itself is not sustainable”), or “conservationists” who want to preserve London’s (lack of) skyline: “sad dorks who yearn for stasis, who can’t acknowledge that, whatever they do, the future will happen and it will be different, it will have to be tall”. Meades loves cities, of course. “Townscape is the highest form of museum,” he insists, and, when writing about the Third Reich (some fascinating pieces here on that era’s obsession with esoteric rubbish, as well as its bad architecture), he makes sure to remind us that the Nazis “started out as resentful hicks. Cities are mankind’s greatest collective achievement; it is (back to) nature that is unnatural.”

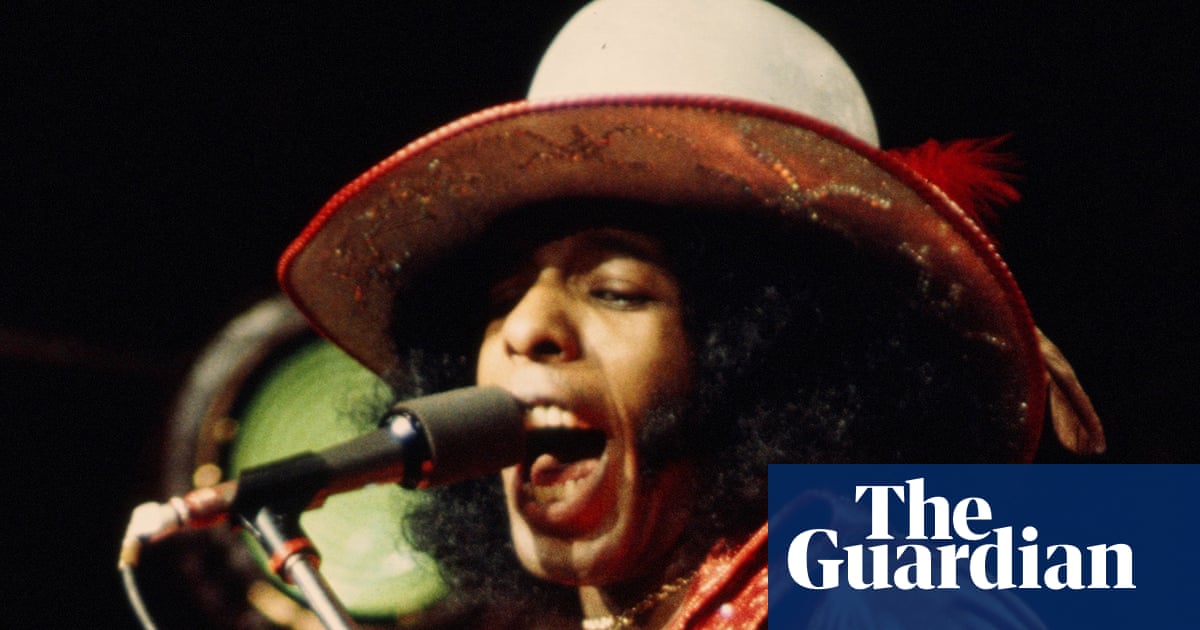

It shouldn’t be thought that this book comprises nothing but screeds. There are, too, filthy jokes in French and fond obituaries of the celebrity cook Jennifer Paterson and writer Lesley Cunliffe. Meades likes the writing of Elizabeth David, the novels of HG Wells and Flann O’Brien; he writes admiringly about Simon Jenkins on churches, Julian Barnes on art, and the satirical cartooning of Steve Bell and Martin Rowson. The latter he dubs “fast art”, though not all fast art is found worthy of his attention: he is not much for rock and pop music, which he refers to with a pair of scare-quote tweezers as “music”, as though it is only pretending to be music. (Though how?)

Meades offers intriguing appreciations, in particular, of two men with hidden depths and kindred spirits. Addressing John Major in print, he writes: “You will come to be seen as the last prime minister who had about him the Tommy spirit of the conscript army which won the war: there was something bolshie and obdurate about you and a sense of eccentricity suppressed – beneath your middle manager’s disguise there was a true son of the circus, a daring virtuoso who could and did get to the top of the greasy pole without a safety net.” Do Meades’s celebrated suits furnish similar camouflage?

Reviewing the autobiography of Bob Monkhouse, meanwhile, Meades delights in the comedian’s droll intelligence (Monkhouse refers to one Oldham venue he played as “a fog of armpits and chip fat”), and in his remarkable career of slumming it for success. “What distinguishes Monkhouse from virtually everyone else in illegitimate theatre,” Meades writes (“illegitimate theatre”!), “is the fact that he has a lot to spare. He’s not stretching himself; he doesn’t believe in it.” Ah, our author embraces a fellow sceptic. “Monkhouse is a broadsheet posing as a tabloid. He has made a career out of abasing himself, out of sedulously refusing to realise his potential. And he seems not to possess a pathological need to be loved. When he invented himself, he quite forgot about ‘sincerity’.” Elsewhere, Meades (interviewing himself, for who else would be up to the job?) claims he too lacks “the light entertainer’s or politician’s creepy yearning to be liked”. Which, of course, is a clever way of making people like you.

Probably we don’t deserve Meades, a man who apparently has never composed a dull paragraph. What other living writer has a YouTube channel devoted to low-res digitisations of his TV documentaries that the bootlegging uploaders have literally called a place of worship: the Meades Shrine? A consistent sceptic would bristle, but then Meades himself here praises another writer for his “indifference to the paltry virtue of consistency”, so I think we can make an exception.

Pedro and Ricky Come Again: Selected Writing 1988-2020 by Jonathan Meades is published by Unbound (£30). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.