In 1964, 21-year-old Sylvester Stewart of Vallejo, California talked his way into a job at San Francisco’s KSOL radio and adopted the hipster alias Sly Stone. “Sly was strategic, slick,” he explains in his peculiar memoir. “Stone was solid.” You would have to say that most of his life has been neither sly nor stone.

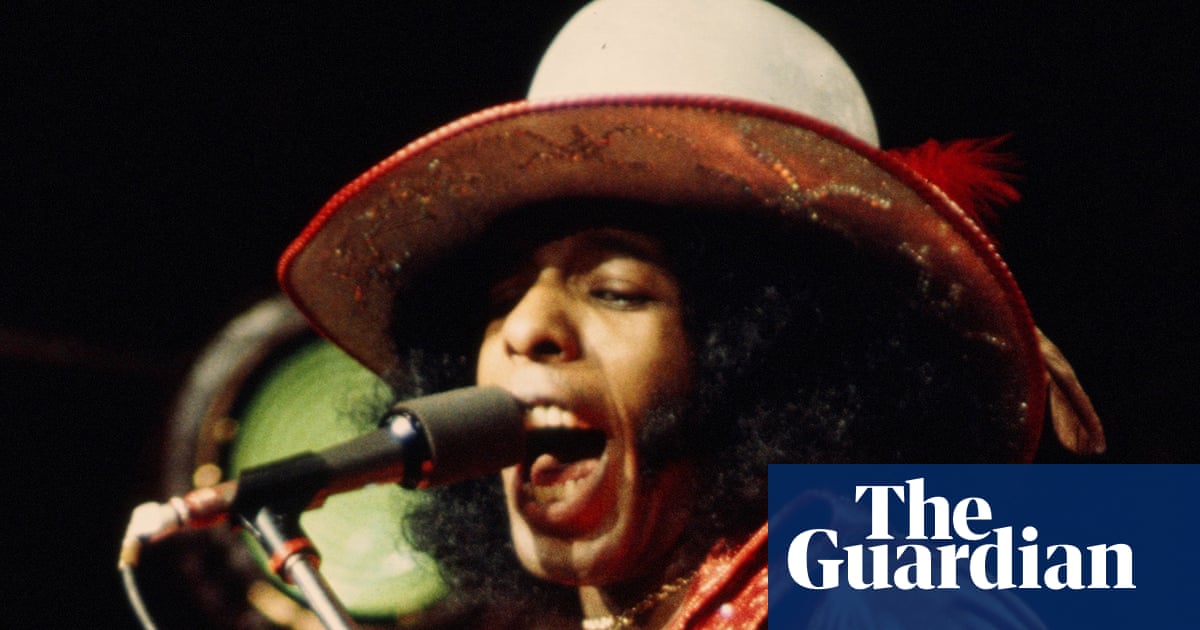

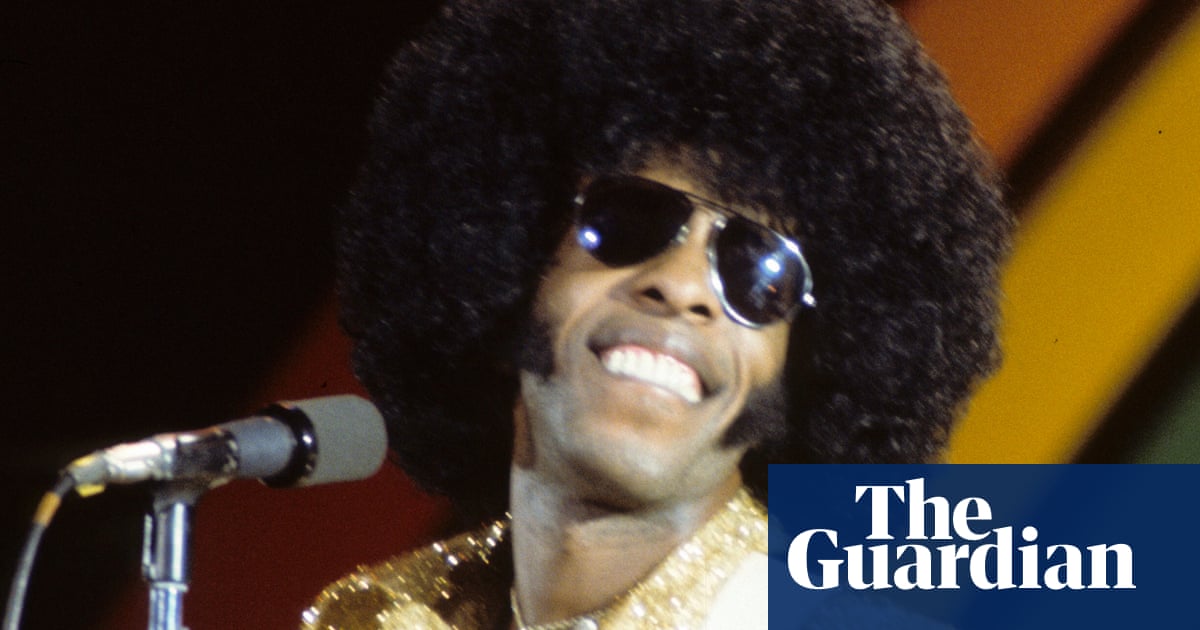

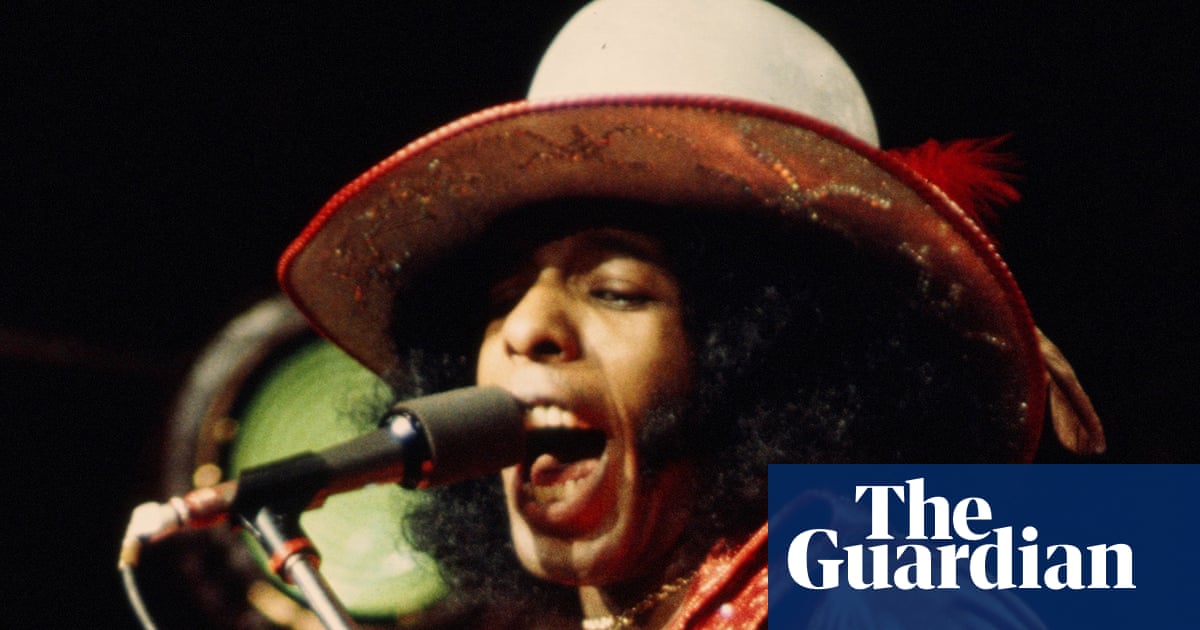

For a couple of years at the end of the 1960s, Sly and the Family Stone were the world’s most transcendentally exciting band: black and white, male and female, a show-don’t-tell advertisement for the ecstasy of unity. Look up their 1968 performance on The Ed Sullivan Show and see Sly and his sister Rose shimmy like the future through the very white, very square audience. Yet within three years that dream was dead. Stone flew so high and crashed so hard that he became a living metaphor for thwarted hopes and foreclosed utopias.

Stone is 80 now, his health wrecked by decades of crack addiction. He hasn’t released an album of new material since 1982; his comeback shows in the late 2000s ranged from disappointment to fiasco. So it’s unclear how much of this book is his and how much is down to his seasoned co-author Ben Greenman. While it’s conceivable that Stone insisted on quoting extensively from old album reviews and talk show appearances, and diligently ticking off every major news event of the late 1960s, it feels more like tactical padding. Stone’s authentic voice flares up in his love of paradoxes (jazz “could be interesting even if it was boring”) and wordplay: “Contradiction, diction, addiction.” Perhaps due to his slippery conception of both time and memory, he is not a natural storyteller. His reminiscences of Muhammad Ali, Richard Pryor and Stevie Wonder are strangely bland, bar his sharp assessment of Jimi Hendrix’s aloof cool: “It frustrated me. It was like he didn’t know what the world could do to him.” Presumably Stone knew, but that was no protection.

The young Sly Stone was an outrageous talent. By the time he formed Sly and the Family Stone in 1966, he had already been a doo-wop singer, a star DJ and a staff producer for Autumn Records. The group he designed embodied the 1960s’ highest hopes. They were an everything band – soul, funk, jazz, rock – whose example psychedelicised Miles Davis and Motown. Stone himself was Prince before Prince. They wowed Woodstock. So what went wrong? Everything.

Stone seems to endorse the conventional wisdom that the mind-warping effects of fame and addiction mirrored the national zeitgeist. His 1971 album There’s a Riot Goin’ On, framed as a salty response to Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, was the sound of implosion. Notorious for blowing out shows (he blames shady promoters), he holed up in his Bel Air mansion, the paranoid patriarch of a disintegrating family. Bassist Larry Graham became convinced that Stone had taken out a contract on his life and took to checking beneath his car for bombs. Stone dismisses that idea but confirms one hair-raising rumour: his terrifying pitbull Gun did indeed kill his pet baboon and then have its way with the corpse. Alarmingly, Stone describes Gun as his “best friend”.

Stone’s career didn’t collapse overnight. There’s a Riot Goin’ On shot to No 1 and his next two albums went gold. His 1974 wedding to actor Kathy Silva at Madison Square Garden was a media sensation, covered at length in the New Yorker. But the albums became less and less impactful before fizzling out all together: fans of the movie Boogie Nights will find the book’s 1980s section familiar. Stone complains that journalists were only interested in drugs and decline, but that’s what happens when the music stops.

A cleaned-up Stone signs off with some watery opinions about politics and music – a wan conclusion to a frustrating book. Did he really meet Frank Sinatra one night? Is it true that he once interrupted a party by waving a gun while freaked out on angel dust? He can’t be sure. “The details in the stories people tell shift over time,” he muses, “in their minds and in mine, in part or in whole, each time they’re told.” It might have been more rewarding to play with his mysteries and evasions instead of trying to wrestle his life into a conventional narrative: let Sly be sly.

Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Again) by Sly Stone is published by White Rabbit (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.