ypical. You go for months without any culture, then 5,000 years of it come along at once. That’s what the V&A’s luxury coach tour of a blockbuster promises, and delivers, including quite brilliant recreations of Iran’s two most renowned sites, Persepolis and Isfahan. Epic Iran shows there is a cultural history that connects the country as it is today with the people who lived here five millennia ago. To put this in perspective, that’s like telling the story of Britain from before Stonehenge to the present and hoping it all connects up somehow. But in Iran, it does.

That’s partly because of a pride in history that preserved traditions across the millennia. The most important document of that is The Shahnameh, The Book of Kings, written at the start of the 11th century CE by the poet Ferdowsi. Iran had been converted to Islam in the seventh century, but Ferdowsi’s epic is packed with the heroic deeds and bloody battles of the ancient, pre-Islamic Sasanian empire. It is also written in Persian, as opposed to Arabic. There are gorgeous manuscripts of this classic. A masterpiece made in Tabriz in the 1500s for the Safavid ruler is open on a battle scene in which bejewelled horsemen charge each other across a sea-like expanse of blue: the painter takes time to depict little flowers blooming on the battlefield, just before the horses trample them.

That eye for nature is rooted in antiquity. A pottery jug in the shape of a humpbacked bull from 1200-800 BCE, a golden bowl from the same period with exquisite 3D gazelles bursting from it, and many more horned and frolicking beasts fill the earliest art here with animal life. In the Persian empire, which ruled much of the Middle East in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE, the beasts become even more mythic and ornate. An armlet has horned griffins on it, in gold, lapis lazuli and other precious stuffs.

The Persian empire is brought to stately, ceremonial life in one of the exhibition’s big set pieces. Real treasures such as a spindly gold model of a chariot and huge horn of plenty drinking vessels are displayed among ever-changing virtual images of Persepolis, as it was and is now. Persepolis was built for rituals and tribute ceremonies, not living in: its mystique soaks in as you watch a cast of its sculptures change colour to show how it was originally painted. Yet even here there was room for artistic delicacy. A real chunk of the reliefs of Persepolis, lent by the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, shows one courtier touching his friend’s beard in a gesture of intimacy: the other reciprocates with a similarly warm tap on the shoulder.

Alexander the Great torched Persepolis and crushed the Persian empire. You can read the ancient Greek historian Herodotus if you want to see what the Persian empire looked like to outsiders and how the Greeks defined themselves, and hence “the west”, against it. What you get here is the view from inside. The ruler Cyrus the Great speaks for himself on the Cyrus Cylinder from the British Museum, a clay roll incised with cuneiform letters telling how Cyrus has restored religious rights in his empire.

The artistic richness of Iran has to have come from its geographical openness to east and west, absorbing influences from China, Mesopotamia, Greece, the Mongols. That gives Persian Islamic art a subtle strength that in turn influenced the whole Islamic world. Readers of Orhan Pamuk’s My Name is Red will know that as far away as Istanbul, miniaturists illustrated the Shahnameh and imitated the Persian masters.

This artistry went into overdrive when the Safavid empire united Iran behind Shia Islam in the 1500s. And the V&A makes its dazzling capital Isfahan materialise around you. One of the reasons it can do so is that the Victorian founders of this museum commissioned full size copies of some of Isfahan’s most beautiful decorated walls and domes. These flow up around you, their colours merging with video images of Isfahan’s architecture on a dome-shaped screen above. I have never been to Isfahan but in palaces and mosques I’ve visited, it is the ensemble of light and space, sun catching on lustrous tiles, domes cooling the mood, that creates magic. They catch that rhapsodic feeling here.

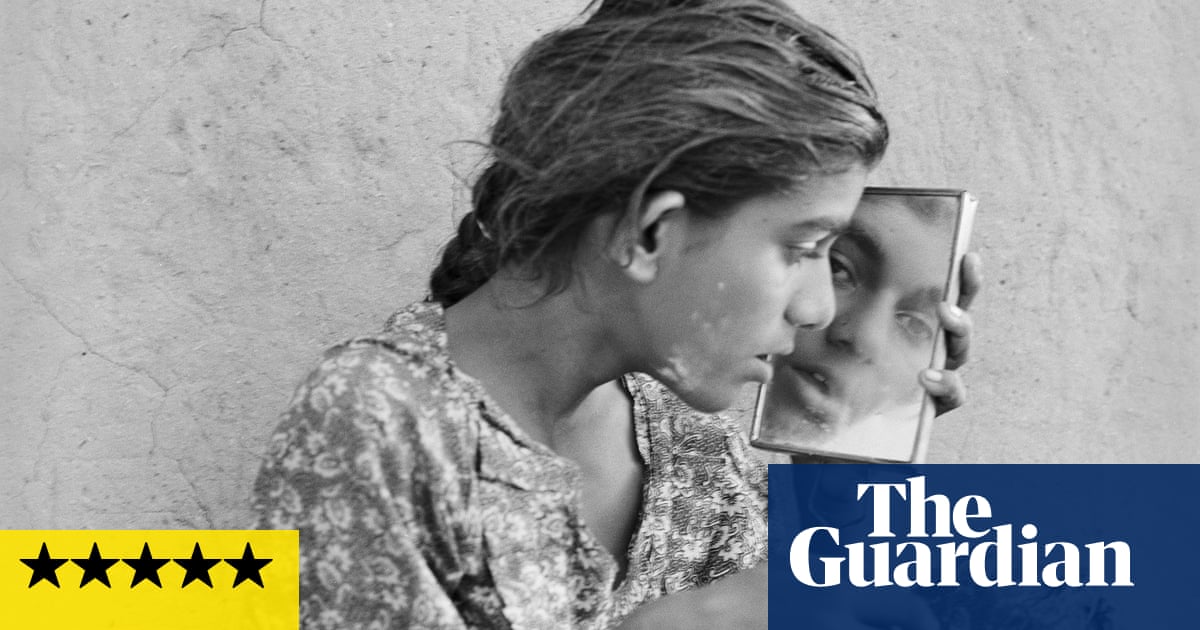

Then, like Coleridge disturbed in his reveries of Kubla Khan, I was punched awake by reality. A 19th-century painting shows the women of a harem, and you realise the Persian past was not all poetry and paradise. Shirin Neshat’s 1998 video Turbulent makes a similar point. Across a dark space, two singers face each other on separate screens. While a man sings a medieval love poem by Jalal al-Din Rumi, a woman, alone in the dark, responds with an anguished wordless wail. There isn’t any model for her feelings, or the world she imagines. Iran’s next 5,000 years are still to be written, and the past probably doesn’t offer any answers.