Humans have done a lot of horrifying things. But now the tables have turned, and the human race faces unprecedented peril, nature’s wrath after years of abuse. Photography can only grapple with the enormity of what is happening as the world that we know disappears.

The theme for this year’s Prix Pictet – one of the world’s top photo prizes – is Human. The prize has always favoured titanic themes, but the exhibition of this year’s shortlist of 12 is a spectacular and profoundly melancholy reckoning with what we humans have done, where it’s left us, and where we’re heading.

The winner of the 2023 Prix Pictet, announced at an award ceremony at the V&A on 28 September, is the Indian photographic artist Gauri Gill. Gill is the 10th photographer to pick up the 100,000 CHF (£89,700) prize and follows an illustrious list, including the last winner, Sally Mann.

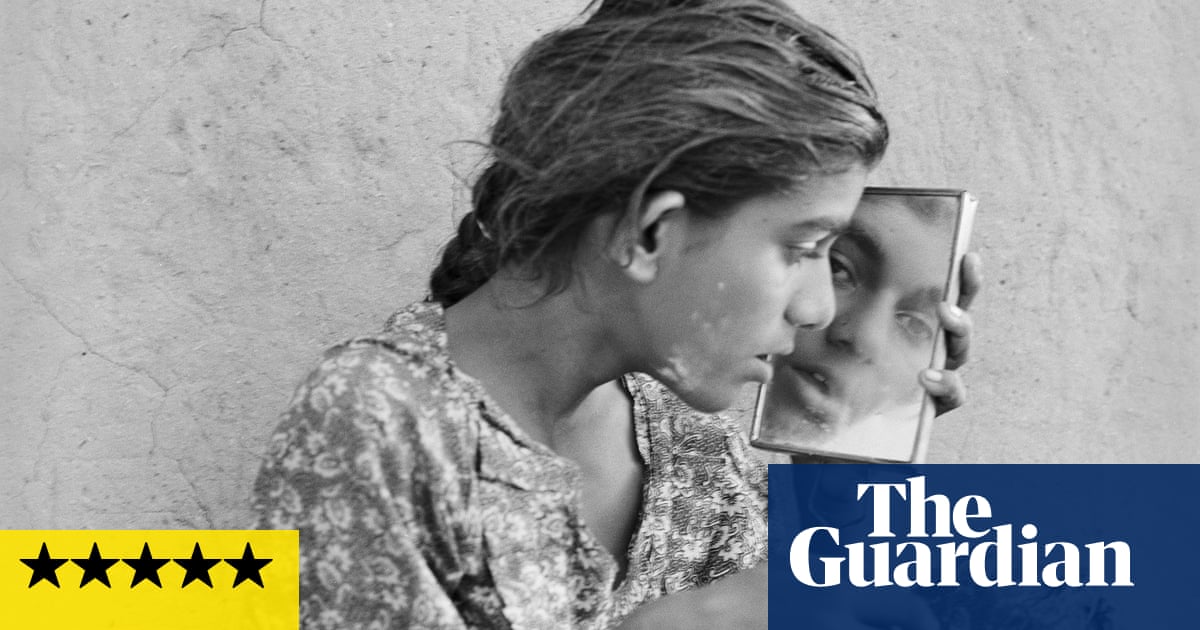

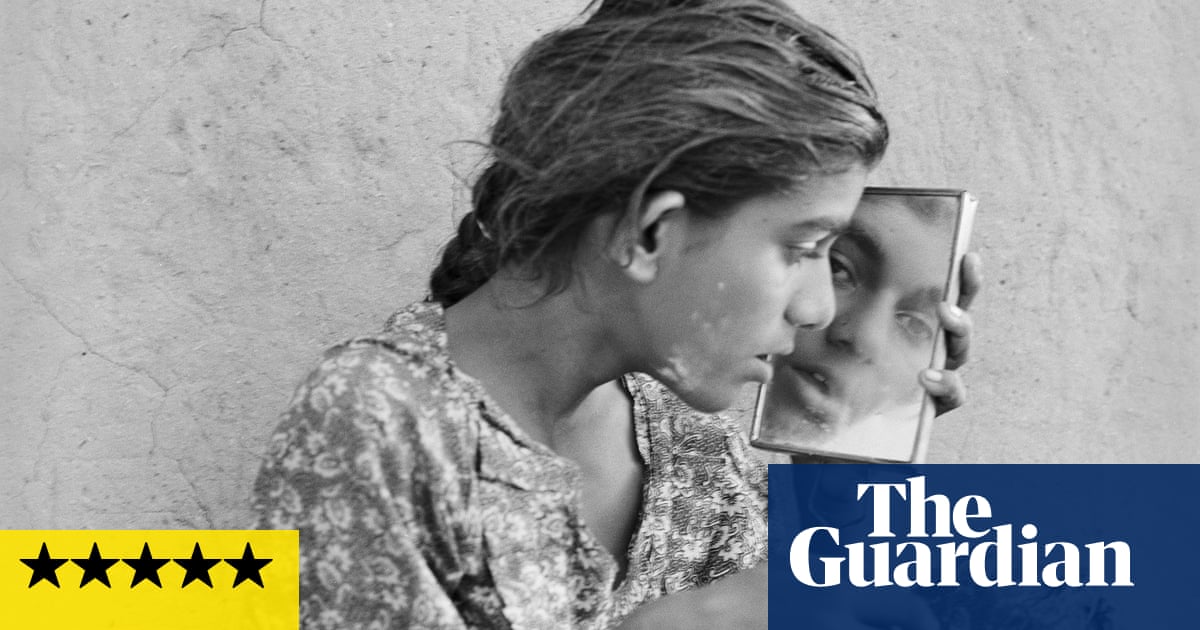

Gill’s winning series, Notes from the Desert, began with an act of brutality she witnessed at a village school in rural Rajasthan, north India, when a girl was beaten by her teacher. Unable to shake the image, Gill took a month off work and left Delhi to return to Rajasthan and photograph the villages. At first her focus was the schools, but her project, which began in 1999 and is still not complete, quickly expanded to bear witness to life and death in the desert.

Over the years, Gill forged relationships with many of the villagers, and returned again and again. The taut selection of images on show are exquisitely printed, reminiscent of Graciela Iturbide’s black and white studies of Indigenous communities in Mexico in the 1970s, and suffused with the same kind of magical realism. Soft, tender and strange, the images also hold the harshness of the reality they show, a place that demands total self-reliance, and where, as Gill has said, “the stakes are high, the elements close, and life is as cheap as the jokes are rampant”.

The show is not without glimmers of hope – a literal glimmer, in the case of the show’s opener, a deeply moving and wistful series by Mexican photographer Yael Martínez. The shadowy surfaces of his nocturnal photographs glitter with dozens of dots of dazzling light, creating the effect of the eponymous Luciérnaga (Firefly), or recalling the constellations of candles held during rituals for the dead in Mexico. Martínez punctured prints of the images with pins, shone a torch through the holes, then photographed them again. The people in the pictures are escaping violence endemic in their communities in search of a better life. As the light perforates the darkness in paroxysms of positive energy, the images are transformed – a metaphor for the way humans can turn things around, how the soul resists and flourishes, in spite of the body.

From poetry to putrefaction: the Colombian photojournalist Federico Rios Escobar, known for his documentation of Farc in the jungle and gangs in El Salvador, presents a series called Paths of Desperate Hope. Shot at the Darién Gap, the region that connects Colombia to Panama, last year Escobar followed migrants – forced from their homes due to climate change, economic desperation and conflict – as they made a treacherous trek from a beach town in Colombia to a government camp in Panama. One image depicts a body dredged from the river, maggot-infested and bloated by the water, barely recognisable as human. Just as devastating is the inconclusiveness of Escobar’s project. “I’ll never know how many of those we met made it – and how many didn’t,” he said.

But humans can surprise us – and photography still has the power to lay us bare and connect us. The idea for The Garden by British artist Siân Davey came from her son: replant the abandoned garden at the family home in Devon, and invite people they met over the back wall to come and be photographed. The garden became a “confessional space” for Davey as she photographed her subjects; the stories remain private but we project them into the lush, large-scale, full-colour prints, the verdant bounty of Davey’s garden in full bloom framing the perfectly imperfect, semi-clad bodies that hold each other.

Two distinct and equally powerful bodies of work focus on children, perhaps the show’s only hints at optimism. Vasantha Yogananthan photographed children born after Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans. Partly posed, partly freestyle, the portraits convey the essence of childhood days, carefree – unaware of the disasters that have come before and are possibly yet to come.

In contrast is a suite of jewel-like black and white prints of young schoolgirls in the Turkish region of Eastern Anatolia by Vanessa Winship. The girls, in their austere uniforms and homemade haircuts, seem to be from another time. Getting an education, for girls living here, is not easy. The hardship comes at you through the details: the battered residential buildings behind the girls, the brittle earth beneath scuffed shoes. But commemorated in pictures, the occasion is no less momentous than children heading off to their first day at school anywhere – even in black and white, these girls are radiant with promise.

Human is an exhilarating viewing experience. It is a show about human persistence as much as it is about the urgency of the climate crisis. It is about greed, and love. It is about our mortality. And it is scary. But if the camera is a sincere witness, how could it tell us anything else?