was one of the first Muslim imams in the United States military. Clergy defend the right of US military personnel to practise their religion. This means providing religious support, taking services and advising the commander in religion, ethics and morale.

I grew up in New Jersey as a Lutheran and was still a Christian when I graduated from the military academy at West Point, but I met someone who opened my eyes to Islam and its similarity to the other Abrahamic faiths. I converted in 1991.

After West Point I left the army to follow my own spiritual path, living in Syria and learning to read the Qur’an properly. By the end of the decade, the US military, perhaps out of political correctness, was looking to recruit imams, so I had my first posting in Fort Lewis, Washington.

A few years later, I was asked to go to Guantánamo Bay. My wife was from Syria, she had no family in the US and we had a baby daughter. We were just settling down. But the army insisted and I was flattered to be offered the challenge. Just after the first anniversary of 9/11, I shipped out to Guantánamo to become the imam there.

It was November 2002 when I arrived, but the air was humid and hot. At Camp Delta, the permanent detainment camp, the prisoners were held individually in cage-like cells made of heavy-duty steel mesh. It was something the outside world had no idea about at the time.

I worked from sunup to sundown in chaotic circumstances, where prisoners were abused and humiliated on a daily basis.

On my daily visits, the prisoners often told me about what they had to endure in interrogation sessions. I witnessed some of the broken teeth and bruises that many came back with. Despite the physical abuse, most of the direct complaints I received were about religious persecution. Guards desecrated the Qur’an and made the prisoners bow at the centre of satanic circles. The official military line was that torture did not happen at Guantánamo. As an insider, I knew this was a lie. Some guards were great, while others were abusive.

I was aware of who the likely abusive ones were because when I came on to the scene, they would alert the other guards with a shout of, “Chaplain on the block.” There were three prisoners held in a separate location – Camp Iguana – because they were only 12 to 14 years old. The guards there were excellent.

I performed the Muslim prayer service at the chapel every Friday and led a vibrant American Muslim community. This raised suspicions, and FBI agents would turn up at the chapel to monitor us.

When I began submitting formal reports on how the prisoners were being abused, I was accused of siding with terrorists. It became clear the officers in charge wanted me out – I was marginalised and under surveillance.

Towards the end of my tour, I took two weeks of leave, with the intention of going back to Fort Lewis to set everything up for the return of my wife and daughter. I left the base and got on a plane to the Jacksonville naval station in Florida.

When we landed, I was taken to a room and questioned by the FBI. I was charged with spying, espionage, aiding the enemy, mutiny and sedition.

After being imprisoned in Florida for six days, I was moved to the Consolidated Naval Brig in Charleston, South Carolina, where I spent 70 days, mostly in solitary confinement. On the way there, I was subjected to the same sensory deprivation and shackling I’d seen at Guantánamo. It was a harrowing ordeal.

Although I was cleared of all charges and returned to Fort Lewis, it became clear that I wasn’t trusted.

The Bush administration failed my country and the world in the most grievous way. They set up the prison at Guantánamo Bay believing it would be outside the law. Very early on, they knew that most of the prisoners were innocent, but they kept them there because releasing them would look bad.

I had great hopes for Barack Obama when he said he would close the prison camp, but those hopes vanished. It’s Joe Biden’s obligation now to fulfil Obama’s promise.

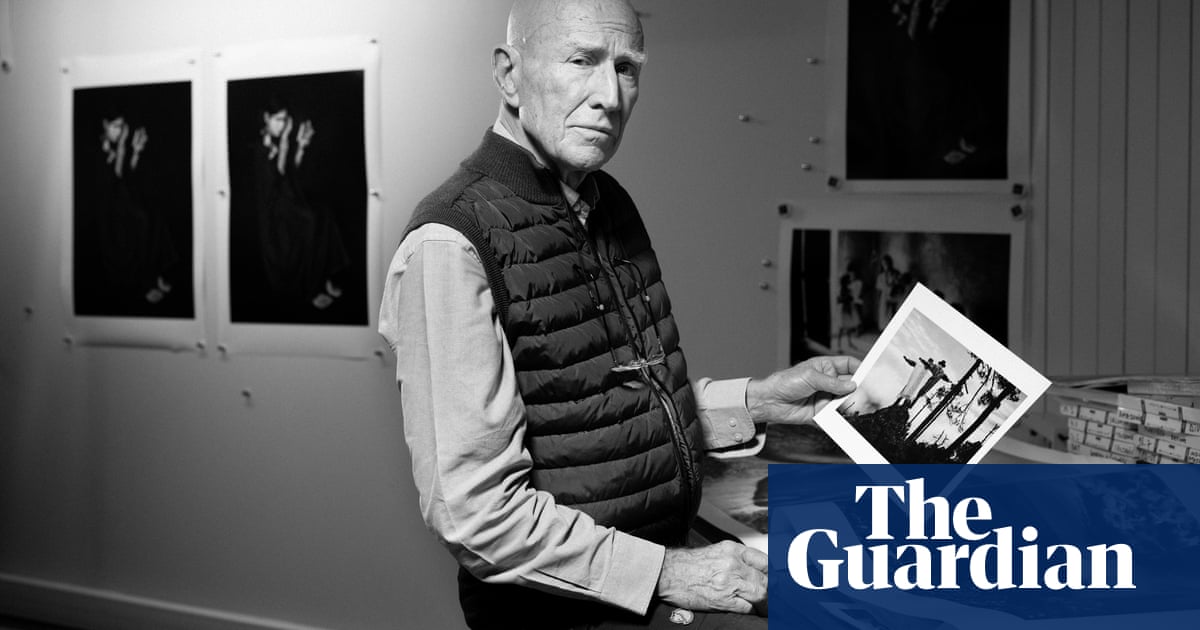

Today, I work with veterans, using art to help them come to terms with the horrors of war. In part, I left so I could tell my story, to speak the truth about Guantánamo. I’ve been doing that ever since.

As told to Oscar Rickett

Do you have an experience to share? Email experience@theguardian.com