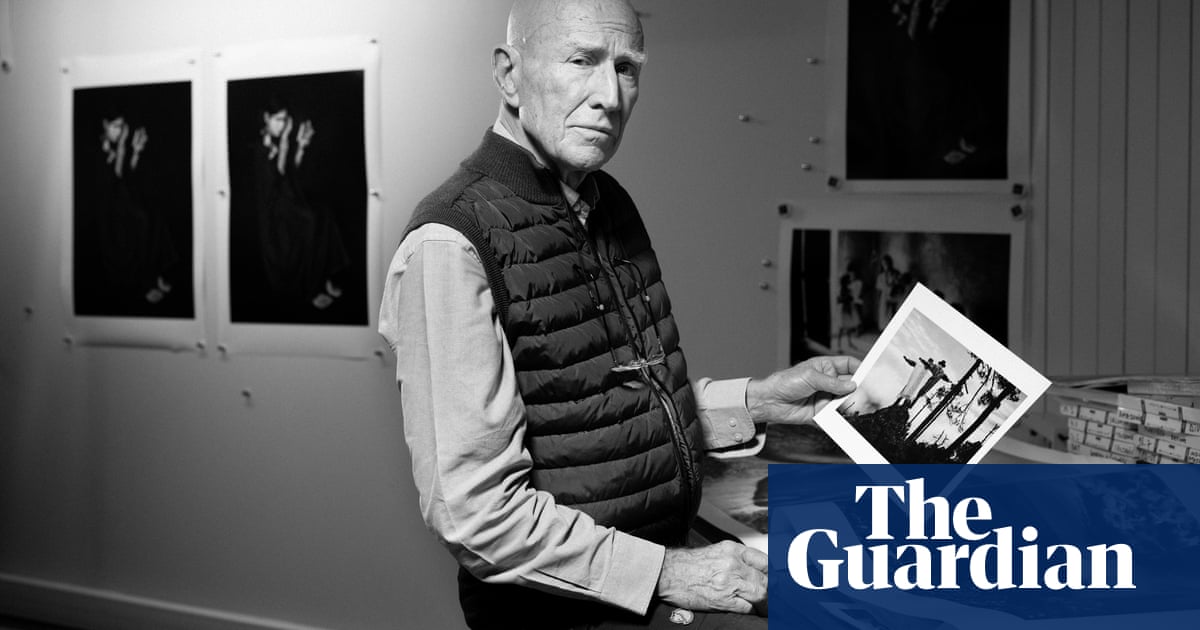

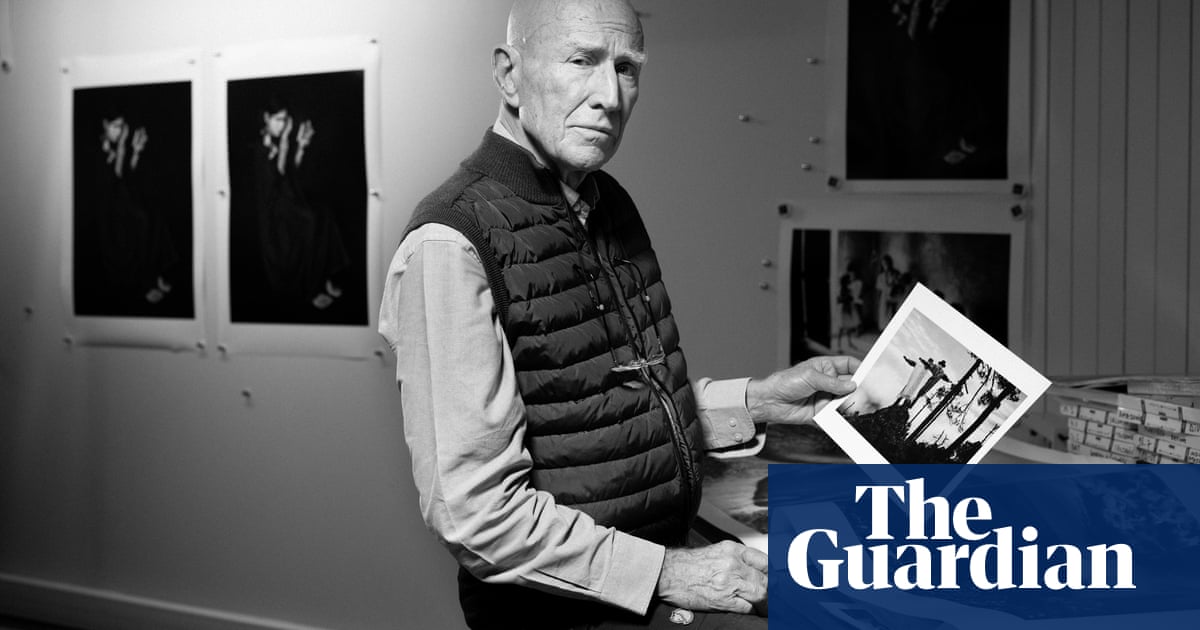

‘Iphotographed the world,” says Sebastião Salgado, flicking through the archive in his Paris studio. Salgado, who turns 80 this week, has witnessed wars, revolutions, coups, humanitarian crises, and famine. He has also seen some of the most pristine places on the planet – locations and peoples untouched by the devastating fury of the modern world.

His body of work, an instantly recognisable combination of black-and-white composition and dramatic lighting, has been built up over decades, covering hundreds of assignments in 130 countries and his name stands in the photojournalist pantheon alongside figures such as Robert Capa, Eugene Smith, Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson, James Nachtwey and Steve McCurry.

Now, Salgado tells the Guardian, it’s time to step down. “I know I won’t live much longer. But I don’t want to live much longer. I’ve lived so much and seen so many things.”

Although still strong and active – able to walk or cycle several kilometres a day – his body is paying the price for his years working in some of the world’s most hostile and challenging places.

Still living with the legacy of a blood disorder from improperly treated malaria caught in Indonesia and problems with his spine from a landmine that blew up his vehicle in 1974 during Mozambique’s war of independence, Salgado is ready to retire from the field.

That is not to say he has completely finished. Now, he has become the editor of his own monumental archive, which 15 years ago numbered about 500,000 works. A new count is under way as a first step to selling it.

There is no shortage of projects for him to focus on. The next one is the Sony World Photography Awards 2024 exhibition at London’s Somerset House, from April, which celebrates his Outstanding Contribution to Photography award. There is also a collaboration with the Wende Museum in Los Angeles on industry in the Soviet Union, which he describes as “the workers’ paradise”. Yet another project will bring together some of his earliest pictures at São Paulo’s Museum of Image and Sound.

Salgado is also preparing for a special show during Cop30, to be held next year in Belém, northern Brazil. “We will open an exhibition with 255 giant pictures from my Amazônia project and a concert with compositions by [Heitor] Villa-Lobos,” he says.

In the basement of his studio, stacks of thousands of pictures await his attention. Upstairs, Lélia Wanick Salgado, the architect and former pianist to whom Salgado has been married for 60 years, manages the agency, produces new exhibitions and works on the concept, design and editing of his books.

“I can’t say where I end and where Lélia begins,” says Salgado of the woman he met when he was 19. “She is central in my life.”

Salgado was born in Minas Gerais, Brazil, where he met Wanick when she was 17; she graduated in architecture, he in economics. Both were members of a revolutionary leftwing group and as political persecution increased under the 1964-85 Brazilian military dictatorship, the couple decided to leave the country for self-imposed exile in Paris.

It was not until he borrowed Wanick’s camera, aged 29, that Salgado discovered his talent for photography. His rise was meteoric in Paris, where agencies such as Sygma, Gamma, and Magnum thrived. Salgado passed through all of them and made his mark at Magnum, where he became one of its star photographers.

“I was studying architecture, had to do my assignments and bought myself a camera. Tião then took the camera. I could hardly [get it back]! And that’s how he really got into photography,” Wanick recalls. “I didn’t recognise his talent straight away. But we started going to many exhibitions, studying the history of photography, and that’s how my interest in photography was born.”

Wanick would later become director of Magnum’s Paris gallery before opening an independent studio, which over time became dedicated to Salgado’s output. Her work is widely recognised as the key to her husband’s success.

“Salgado wouldn’t be Salgado without Lelia. She is central to everything he’s done,” says Neil Burgess, who has been his agent since 1986. “She is not just his wife, the mother to his children, but also a creative partner and a business partner to his career. They discuss everything.”

Salgado left Magnum in 1994. The break-up freed Salgado and Wanick to work on their own projects, but came at a cost. Many former colleagues saw Salgado leaving the agency as an act of betrayal.

Exodus, his first major project after the split, faced harsh criticism from his peers, who accused Salgado of being a “leftwing militant”, of “exploiting and aestheticising misery” and, later, of “violating pristine places and peoples”.

“I’ve seen wonderful photographs by Richard Avedon, Annie Leibovitz and great European photographers,” he says. “There has never been criticism about the way they used light or the composition they created. But there has been about mine.

“They say I was an ‘aesthete of misery’ and tried to impose beauty on the poor world. But why should the poor world be uglier than the rich world? The light here is the same as there. The dignity here is the same as there.

“The flaw my critics have, I don’t,” he says. “It’s the feeling of guilt.

“I was not born here [in Europe]. I came from the third world. When I was born, Brazil was a developing country. The pictures I took, I took from my side, from my world, from where I come,” says Salgado.

Today he is able to respond emphatically to the criticism, but at the time, Salgado felt the blow keenly and withdrew. “It was a moment of deep disillusionment with my own kind, and I wanted something else,” he says.

“I didn’t want to be a photographer any more. That’s when I [joined] the Instituto Terra.”

It was a moment of profound transition: nature replaced people as his central interest. The Instituto Terra, an environmental organisation founded in 1998, was was an initiative of Wanick’s which came about when the couple realised how the environment in Minas Gerais had been devastated by human activity. They set out to recreate the forest that had once existed, restoring the degraded landscape.

Wanick and Salgado began collecting seeds, trained rural technicians and planted millions of trees. “We started with a nursery of 25,000 trees, then expanded to 125,000. Today, our nursery has [space] for 550,000 trees a year, and next year, we will increase it to 2 million,” he says enthusiastically. “It’s fantastic!”

Connecting with nature made Salgado rediscover his passion for photography, leading to two of his most significant projects: Genesis (2013) and Amazônia (2021).

“There was this transition from man to nature at a time when everyone was heading towards nature,” he says. So they came up with the idea of visiting and documenting untouched places, representing the 46% of the planet that has remained pristine.

The change of direction extended Salgado’s career by another two decades and has made his work a touchstone for environmental and humanitarian issues.

“My outlook is pessimistic regarding my species, the human being, which has not evolved at all. Our species has isolated itself,” he says, lamenting the blindness of global decision-makers who are not only failing to tackle emissions but also ignoring two other structural problems he considers crucial: the increasing scarcity of water and the catastrophic loss of biodiversity.

“To restore 2,000 water sources in Brazil, we must have spent €25m in these 25 years. It’s a lot of money,” he says, but notes that some governments are ready “to provide a handful of F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine, and each one, equipped, costs €150m”.

The world, Salgado is convinced, is heading towards a global conflict, with “blocs that are already taking shape” based on the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, while efforts to protect the environmental stall. “There is money,” he notes. “Money is not a problem.”

For Salgado, human blindness leads to self-destruction, which is a cause for great pessimism. But nature, he says, continues on its own course and keeps evolving. This lesson he learned in Galápagos, where he spent 90 days – almost twice as long as Darwin, who spent 47 days on the archipelago – and throughout his eight decades of life.

“I am pessimistic about humankind,” he admits, “but optimistic about the planet. The planet will recover. It is becoming increasingly easier for the planet to eliminate us.”