pencer Carter had been signed off work for three months with stress. Before that time was up, his employers “encouraged” him back early, then doubled the size of the team he managed – and his responsibility. “In the last couple of years, everything got worse,” he says, with a degree of understatement. In fact, his GP warned him the stress was going to kill him, thanks to his astronomically high blood pressure. He took, he says, “voluntary redundancy to save my life”.

Although he had tried counselling in the run-up to his redundancy, it hadn’t helped with his overly demanding working environment as a business operations manager for a global company – endless data and spreadsheets, running teams across different time zones, and being responsible for huge budgets in a highly competitive culture.

“I was drinking heavily,” he says. “I could feel my relationship falling apart. My behaviour became erratic. And you can’t turn off. You take a holiday, but you don’t switch off.”

Carter agonised over abandoning a well-paid career he had spent decades building, but in the end he thought, “What am I doing to myself?”

A recent study by the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization found that working at least 55 hours a week was causing hundreds of thousands of premature deaths and was linked to a higher risk of stroke and heart disease. Long hours were described as “a serious health hazard”.

Burnout is the name given to the host of symptoms caused by an overwhelming, stressful environment – including fatigue, muscle aches, headaches and stomach issues, as well as psychological effects such as listlessness and loss of motivation. Numerous surveys have found burnout has increased among workers in the past year, as work-life boundaries have become blurred by people working from home and anxiety over job security has increased. And, for those in jobs directly dealing with the Covid crisis, exhaustion has long since set in.

“Burnout is the cumulative result of unresolved and chronic stress,” says the clinical psychologist Dr Roberta Babb. Generally, there are three main types, she says. You can be burned out by being overworked and overloaded (“frenetic” burnout), but also by its opposite, “boreout”, where you may feel “consistently underchallenged or underworked”. “It may seem counterintuitive but we need a certain amount of stimulation in our daily work and lives in order to perform and feel satisfied,” says Babb.

And then there is “worn-out burnout” – just being ground down: “People have low amounts of energy, and feel exhausted on an emotional, physical and social level.”

Although many people, with supportive employers, can return to their job after burnout, for Carter, this was no longer an option. He was lucky to have a good redundancy package and he turned to his passion (and degree subject), archaeology. He went from a job earning £100,000 to a sector where salaries begin at £19,000, but he loved it. “I got excited again about something that’s a little bit academic, brain-challenging – it took me out of the house. It was frightening, exciting, enjoyable. There was a shift into feeling self-empowered.”

That was in 2011, but his recovery has not been straightforward. In 2017, he had what he describes as “the second round of burnout, what I would call PTSD. Everything hits you, no matter how happy you have been for a couple of years.”

Still, Carter has become a specialist in his field, published papers and successfully changed career, although the pandemic has affected his job and health. “Sometimes,” he says, “I think [changing career] actually saved my life.”

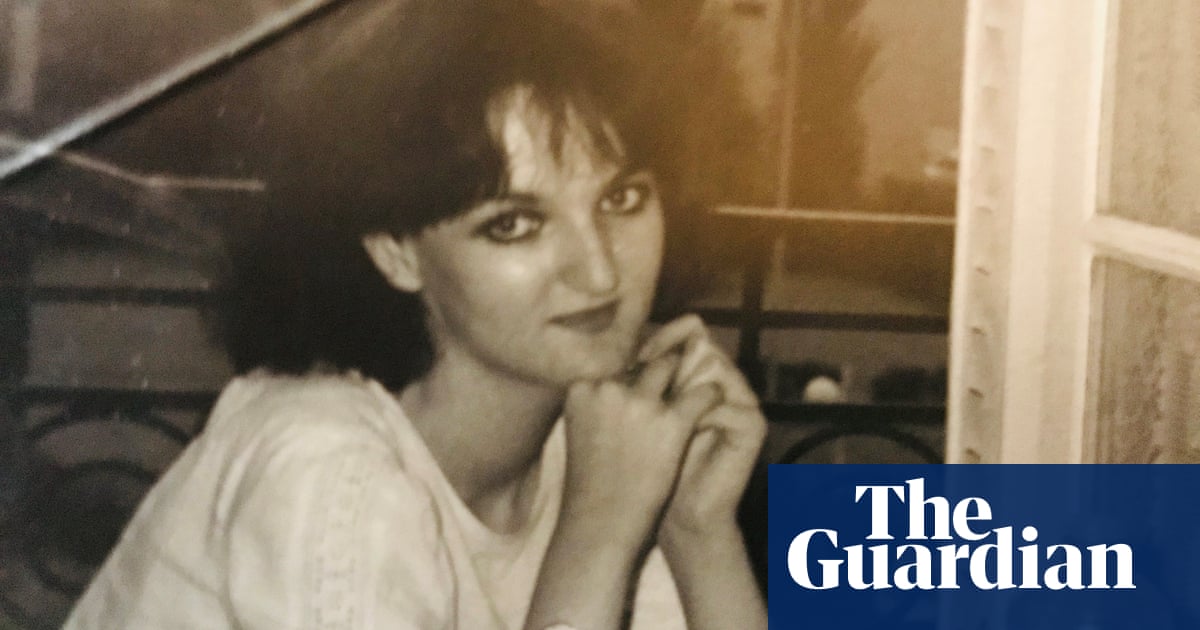

An emotionally rewarding job you love is also not necessarily a shield against burning out, as Tara Lewis discovered after working as a paramedic for 16 years, before leaving in 2015.

A year earlier, Lewis was signed off work for six months. She adored being a paramedic. “You go into it with that whole thing of, ‘I want to do the trauma, the proper emergencies, and make a difference.’”

But over the years, it was becoming too difficult. The number of callouts soared and increasingly they were to deal with social issues, rather than medical emergencies – such as people who were having difficulty accessing healthcare, and were using 999 to get help.

She thinks it took her “a good three years to really feel properly well again” with the help of counselling and antidepressants, although in the first couple of months after leaving her job there was “a massive improvement”.

While she was off work, Lewis decided to start training as a beauty therapist and the next year, when she was offered a job in a salon, she resigned from the NHS.

“It was still working with people, although it’s completely different. I really enjoyed it. It gave me a different focus. I was self-employed, so I could have control over it, which helped. I worked with a lovely bunch of people and had a good laugh. I just found my sense of humour again, and had the time to be able to enjoy life, spend time with my kids, with my husband.”

Burnout, says Mel MacIntyre, a business coach, can make people “call everything into question”. This was her own experience.

“My life looked perfect on the outside,” she says, but her corporate job was taking an excessive toll. It came to a head on the day she took her father to hospital for a big operation, then went into work where she had to make several people redundant. “I woke up one day, and there was nothing left to draw on.”

She had depression, anxiety and irritable bowel syndrome, was being investigated for a possible stomach ulcer and was using alcohol to cope. Her GP said it was pointless just signing her off for a couple of weeks, and advised her to make a serious change.

So, in her mid-30s, MacIntyre quit her job, spent a year travelling and tried “to learn how to relax. I realised I couldn’t keep living my life the way I had been.” She trained as a business coach and set up her own company to help others to avoid burnout. Then she moved from Edinburgh to the Outer Hebrides, started a family and now lives on a tiny, remote island. “It’s so beautiful. It’s got 140 people, lots of wild horses and sheep. There are eagles that live at the back of my house.”

Among her clients, burnout is common. “We’re at a tipping point, I think, where the old world is not fit for purpose any more,” she says. “There’s this narrative in society which is that in order to be successful, you’ve got to sacrifice your health or your relationships, or things that are important to you. You’ve got to hustle. And I really don’t agree with that.”

Others, too, have seen the light. Mays Al-Ali has gone from a successful job in advertising to living in Ibiza and working as a yoga teacher and nutritionist. She had burned out twice – the first time 10 years ago; her hair began falling out and she was suffering from fatigue as well as gut and skin issues. In 2019, she decided to quit completely and start a master’s degree in nutrition.

“It was hard to let go of the security of a career – it becomes part of your identity,” Al-Ali says. “I’m a lot poorer, but happier. A big part of my life now, that was hugely missing in advertising, is helping people. It’s so much more rewarding.” Although it was a little daunting to make the change, she says it never felt frightening. “It was more like saving myself.”

As an executive director at an investment bank, Shivraj Bassi was working such long hours that he was experiencing mood swings, sleep issues, skin problems and weight loss. “Each week, this feeling of dread would manifest itself consistently around 3pm on a Sunday.”

Leaving a successful career seemed like a difficult decision, although he says now “staying and continuing to suffer is also a decision”. He resigned in 2011, but took at least a couple of years to feel better. “It takes a long time, and I didn’t realise that. I think if I had left sooner, maybe that recovery period would have been shorter.” Since then, he has created a wellbeing and nutrition brand, Innermost. It has been daunting but “it’s a healthier kind of fear, it’s not dread. I feel much happier now.”

Roles based on nurturing others: carers, nurses and teachers, all have high risks of burnout. Overwork among doctors has increased since the pandemic. A British Medical Association survey found that more than a third of GPs who responded were considering taking early retirement in the coming year, and a fifth were planning to leave the NHS or take a career break.

Until the end of 2019, Scott Robinson worked for the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman, dealing with complaints about the NHS in England. It was emotional work – he was dealing with people whose lives had been affected by what they believed were failures of care. “Different people [at work] manage it in different ways,” he says. “Some become really aloof and detached.” He was the opposite.

“I would get outraged on behalf of people,” Robinson says. He would worry about them outside of working hours. “You think: ‘Am I actually helping them?’” He had noticed he wasn’t able to manage his stress in the ways he used to, and was becoming much less social. “I didn’t want to deal with people, because I’d been basically dealing with people all day.”

Eventually he left, and decided to train as a massage therapist. “It felt like a good idea to do something that would be focused on people’s wellbeing, and help them relax or heal and those sorts of things. Fortunately, my partner was able to support me in that shift. I was lucky – I wouldn’t have been able to do it the same way had I not had that support, and that’s not the case for everybody.”

One of the characteristics of burnout, says Babb, “is the gradual onset. This, coupled with our ability to either ignore symptoms of stress, or quickly habituate to increasingly high levels of stress, means it can be difficult to identify and address the symptoms.”

For Melike Hussein, burnout was “a slow-burning process”. As an accountant and finance director for an international company, she loved her job. “This is the strange thing. I had a massive aptitude for it – I was the person that got the toughest jobs because I had this mental resilience to deal with it.” One morning, however, when she thought about the prospect of going into the office, “I started to lose control of my body. I started to shake, couldn’t move, couldn’t speak, I was temporarily paralysed.”

Looking back, she could see how stress had accumulated during her 15 years in finance. “I lived with insomnia, I had panic attacks, chest pains, muscular pains. It was highly competitive, working in a tough environment but I never really had the tools to stop stress becoming chronic.” She experienced “brain fog”, and tasks that she had once done in 10 minutes ended up taking hours, “which added to my workload”.

Hussein was signed off from work, and, although she was recommended antidepressants and therapy, found that what really helped her was breathwork – breathing exercises that it is claimed can transform mental and physical health.

She ended up leaving her job in 2016 and retraining as a breathwork and meditation teacher to help others. “Within six months, I had almost none of the previous issues that I had dealt with.”

The good news, says Babb, is that there are “effective ways to manage and reduce the impact of burnout. They focus on developing your stress awareness, and resilience and coping strategies.”

Techniques include mindfulness, self-compassion and setting boundaries (the usual things of exercise, good diet, rest and sleep are all crucial). At work, she advises regular breaks, delegating tasks and reviewing your workload and responsibilities with a manager. And your GP can help. Leaving your job isn’t necessarily an immediate cure, she says. “We tend to underestimate the time it takes to recover. As soon as we start to feel better, we often return to the same environment and use the same coping strategies that triggered the burnout.” And so the cycle starts again.

If you make enough changes, however, you can transform your life for the better. When the coronavirus hit, Lewis decided to use her paramedic training to help out and went on the temporary register for healthcare professionals who had recently left. When a paramedic position came up in a minor injuries unit last summer, she took it. It’s a different type of job – although she is now on the way to becoming a paramedic practitioner, with additional medical training – but it has all the features of the ambulance service she initially loved.

“I don’t know who’s going to walk through the door, I don’t know what they’re going to have wrong with them. But it’s less stressful, it’s a lovely place to work and I’m able to get my teeth stuck in and learn new stuff, which I was missing,” she says.

Lewis is proof that there is life after burnout – perhaps even when returning to a similar job (with critical adjustments). “So far,” she says, “it’s all been really good.”