“When we first started, people would laugh at us,” says Melissa Thorpe as she guides a group of visitors around an exhibition in a vast hangar at Newquay airport. “But now look, we’re only a matter of months from launch.”

Sweeping around a tall black curtain, she reveals a 21-metre space rocket glimmering under red spot lights. Children’s eyes widen and the adults in the group are agog.

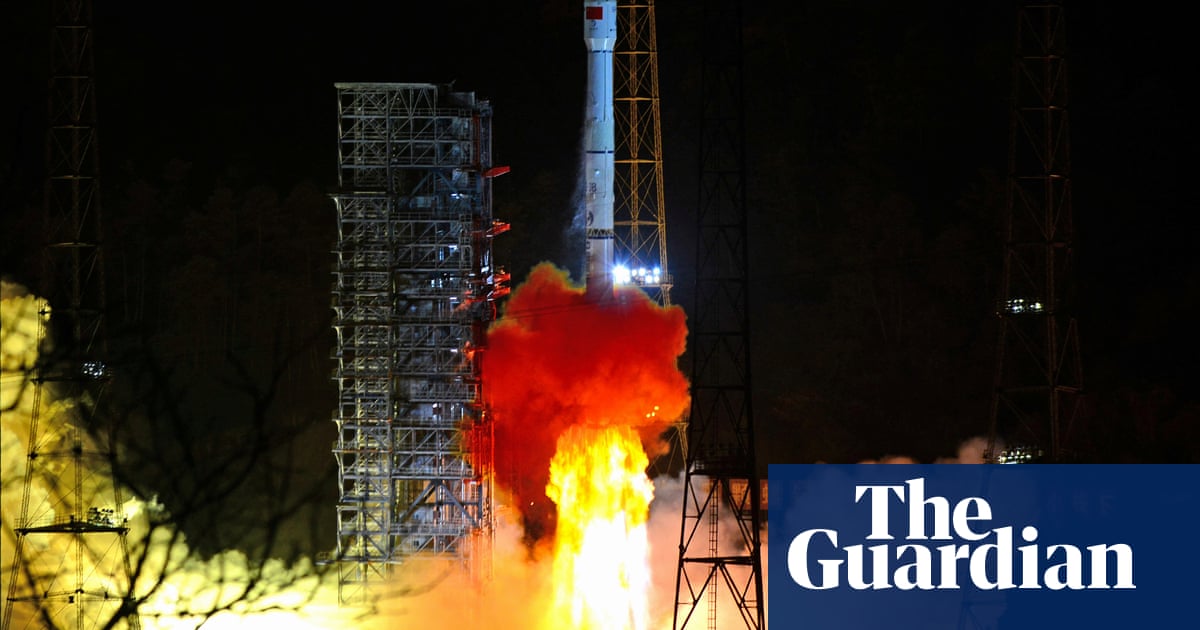

Next year, a rocket like this will be launched into space from the runway outside. Suspended beneath the wing of a modified 747 aeroplane during a horizontal takeoff, it will be propelled into lower Earth orbit carrying government, academic and commercial satellites.

“It’s incredible to think this is happening in Cornwall,” says one visitor. “I thought it was just tourism and pasties round here,” says another, only half joking.

Spaceport Cornwall is one of the cornerstones of the government’s national space strategy, unveiled last month, in which Boris Johnson called for “global Britain” to become “galactic Britain”. Seven spaceports are slated around the UK as the government looks to create one of the most “innovative and attractive space economies in the world”.

Black Arrow became the UK’s first satellite-bearing rocket to reach Earth’s orbit in 1971, but it was launched from Australian soil and the programme was scrapped. Now, under Thorpe’s management, Spaceport Cornwall is the frontrunner in a new and hotly contested European space race.

Using £5.6m of council funding, construction is under way on an 18,500 sq metre hangar at Newquay airport, where satellites will be loaded into the rocket. Meanwhile, Virgin Orbit – the rocket’s owner – has proven its launch capability from the Mojave desert in the US. All that remains is for Thorpe and her team to finalise a licence for takeoff next summer.

“It’s all about getting the UK to launch before Europe,” says Thorpe. “There’s a closing window of opportunity for us to secure the market. We’re ahead at the minute but we’re losing out on time.

“The spaceport site in Wales is looking at balloon launch; the sites in Scotland are looking at vertical launch; there’s one in Sweden; Italy has major ambitions for horizontal launch. We don’t want to see a launch coming from Italy and flying over the top of Cornwall while we all sit here going: ‘Oh, we wish we had that.’”

Such is her passion, it’s easy to picture Thorpe as a childhood space nerd. But she confesses otherwise. “I’m really not much of a space geek at all but I am blown away by what space can do for us here on Earth,” says the Canadian. “I just really want to protect our planet through innovation and I know that satellites can make everything on Earth more efficient.

“Whether it’s for marine protection, lithium mining, farming, offshore wind or tourism – there are so many applications for satellite technology.”

The first payload to launch from Newquay will include a “community” satellite. Kernow Sat 1, as it is known, it will identify coastal locations around Cornwall where sea kelp, which can sequester vast amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, could be regrown.

Thorpe’s environmental ambitions are echoed by Paul Bate, UK Space Agency’s new chief executive. Speaking to schoolchildren in Newquay, he asked: “Do we really need to be doing this stuff in space? After all, we’ve got enough problems on Earth – we just lived through a pandemic, we’ve got a climate emergency.

“But over half of the critical measurements on climate change rely on satellite data. We wouldn’t know what we know about climate change unless we were looking down at the earth from above.”

Patrick McCall, the chair of Virgin Orbit, credits the growth in the satellite sector – and Sir Richard Branson’s willingness to plough a billion dollars into Virgin’s launch technology – to decreasing entry costs for customers.

“The market has totally changed,” McCall says. “Ten to 20 years ago, all of the satellites that were launched were the size of doubledecker buses and they were very expensive to build and launch. You’d spend about five years and a billion dollars to get your satellite up.

“But satellites are now the size of shoe boxes and our max load is 300kg so we can pack a few of them in and launch very cheaply. It’s an amazing time for the British space industry.”

Britain’s first astronaut, Helen Sharman, is enthusiastic about the potential democratisation of space. However, she warns that directives are needed to ensure space is not the next frontier to be irrevocably polluted by humans.

“We need to consider the environmental impact in the upper and lower atmosphere, and we need to have the right regulations for spacecraft in orbit,” she says. “I want them to have transponders, so that we can track them and move them out of the way of other craft, to avoid space debris.

“The problem is simply the numbers of satellites being launched. We need to make sure we’re doing things properly and sustainably. But that shouldn’t stop us being excited.”

Some local residents have expressed reservations. Catherine Smith says: “The amount of money the space economy spends is huge. If 1% of that could be spent on sorting recycling or feeding people, would we be better off?”

Over at Goonhilly Earth Station near Helston, in one of the most remote corners of Cornwall, Ian Jones, the chief executive, is looking out from the old watchtower. Formerly owned by BT, the site is now the first private deep space communication network in the world and will track launches from Spaceport Cornwall.

Goonhilly’s largest antenna, known as Merlin, is charting a Mars rover as it hurtles 300m km beyond the sun.

“We get a load of instructions from our customers, in this case the European Space Agency, and they tell us what they want us to do with their craft such as orbital manoeuvres, taking measurements or getting data,” says Jones.

On the possibilities for regional business development, he adds: “You always get pockets of hidden magic, but what you need is a food chain, an ecosystem, and that’s what Cornwall has lacked in the past. With bigger entities like Spaceport arriving, we can both act as hubs for integration and development. It’s like a snowball.”

The government expects that the global space economy will be worth £490bn by 2030 and Spaceport is expected to directly create 150 jobs by 2025.

Thorpe is keen for Spaceport to diversify and grow. “It’s exciting to launch rockets but we had to ask ourselves what else are we doing when Virgin isn’t here?” she says. “Hence we’re building the Centre for Space Technology – a clean lab where we can work with satellite companies on R&D. A lot of the smaller SMEs could never afford a facility like that so it’ll be great for Cornwall.

“We’ve also partnered with Sierra Space to allow their Dream Chaser craft to land horizontally on the runway here from 2025. If it’s bringing back microgravity experiments, we can process them here.”

Several academic establishments in the south-west are developing courses and training facilities for careers in space, aided by a share of £1.73m from the European Social Fund.Heidi Thiemann, project manager at Truro and Penwith College, says it will start space apprenticeships next year, featuring training in “manufacturing, CAD, programming, propulsion, cryogenics and cool things like that”.

“In Cornwall we have an issue with brain drain as people leave for London,” she adds. “So our aim is to meet with businesses and see what training they need employees to have.”

Noting that Virgin Orbit’s rockets will be built in the US and are partially reusable, Thiemann says local jobs will come further down the supply chain, including processing data. “We’ll have satellite data coming out of our ears!” she says.

Thiemann is also founder of the Space Skills Alliance, which has published a new census on employment in the sector. Released as International Space Week celebrates women in space, the stats make for awkward reading.

“We found that 29% of people working in the UK space sector are women, but only 47% of women say they feel ‘always welcome’ compared with 79% of men,” she says. “We also found that women consistently earn less than men, a gap that widens with age and seniority from £1,000 in junior roles to £9,000 in senior ones.

“It was quite sad to read some of the comments women left on the census regarding issues of maternity pay, missed training and childcare discrimination.”

Thorpe is keen for improvements. “I was moderating on a panel a few years ago about the future of space,” she says. “The panel was made up of five or six men of a certain age from the US military and the first thing I said is ‘this isn’t the future of space’.

“I think it’s really important for girls to see women like me involved in this industry. They don’t have to be an astronaut or an astro-scientist – in future there will be so many other careers, like growing food in space, marketing in space, mining asteroids.”

Back at the exhibition hangar in Newquay, seven-year-old Destiny Whetter from St Austell is immersed in a virtual reality experience featuring CGIs of far-flung exoplanets. “I saw a lava planet and sandy rocks and a water planet,” she says, excitedly. “It was awesome and epic and scary.”

Whetter turns to her mother and confidently declares that the Launcher One rocket will be fired into space when the commander utters the words: “One, two, three, blast off!”

Thorpe is beaming with anticipation at the idea. “It’s been such an ethereal project for so long, it seems surreal to think about it finally happening,” she says.

“The feeling of being alongside my team on the Tarmac, watching it take off after almost 10 years of pain and planning, will be really emotional. It’s going to be historic.”