Idiscovered I was pregnant unexpectedly, in November 2019. My body quickly began to make it clear that my experience was not going to match society’s dominant image of a glowing, happy and relaxed pregnancy. After almost five months of constant nausea – which felt as if I was trying to hide my worst hangover every single day – I hit what I thought was rock bottom. I turned to Google for an answer to my question: “Is it normal to feel miserable when you’re pregnant?” and realised that I ticked all the boxes for antenatal depression. There was a slight sense of relief that I wasn’t the first person to feel like this. But the problem felt too big for me to deal with, and too jarring with what was expected – happiness and smiles – for me to seek any help.

In March, the nausea finally began to subside, and that was enough for me to shrug off my suspicions of depression. I returned to my weekly dance class and was hopeful I could finally get back to being me. Then, on 23 March, we entered lockdown. I spent the next three months seeing virtually no one apart from my partner. I wandered around Tottenham Marshes and managed two garden meet-ups with my mum.

In the summer, when I was 35 weeks pregnant, I went to a routine checkup, and was told that my baby’s heart rate was too high. The appointment was at the Tottenham Hotspur stadium – they had moved the antenatal unit out of North Middlesex university hospital to try to limit the spread of Covid infections. The midwives told me they were sending me to the hospital for further checks and there was a small chance the baby would have to be born that day. I offered to walk. They exchanged looks and insisted I go in an ambulance.

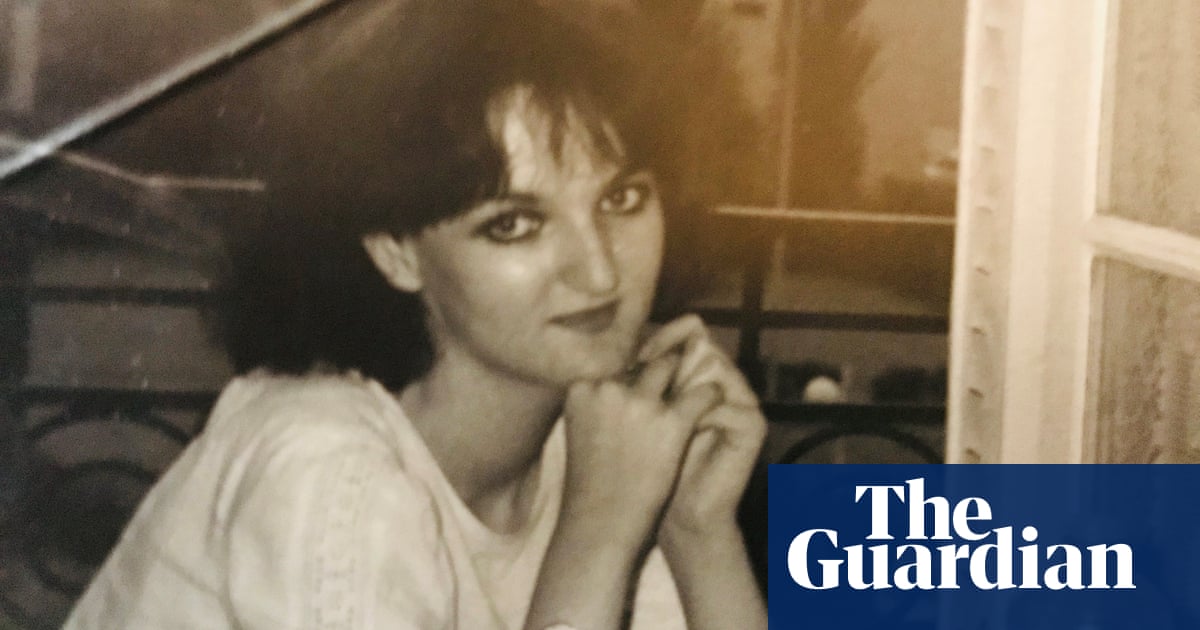

I always assume I’ll be fine, in all situations. I have been conditioned to believe I am a robust person who can shake off illness, pain and discomfort. I am mixed-race and grew up in a small, predominantly white seaside town and I am 6ft tall; the delicate female narrative was not applied to me. I am strong. I was raised by a strong woman to be a strong woman. So, in the ambulance, while the paramedics were taking my details, I was on the phone to my partner reassuring him: “It’ll be fine and I’ll be home shortly.” I’m sure the paramedics knew I wouldn’t be home shortly.

The baby’s heart rate was checked again. A consultant told me the baby was ill, they didn’t know what was wrong and they needed him out as soon as possible. I phoned my partner back and as soon as he said hello, my “strong woman” facade fell to the floor. I couldn’t speak. Tears stuck in my throat. The midwife explained to him that I needed an emergency caesarean section and he should come as quickly as he could.

My baby was born within the hour. I saw him for about 30 seconds, and marvelled at the beautifully long eyelashes escaping from his closed eyes, then he was taken to the neonatal ward.

Because of Covid, only one parent at a time was allowed to visit the baby. We did shifts; mine were the longest for many reasons that didn’t need to be vocalised. There was no chance our family could come to the hospital, or our home. So I was strong again.

We were fortunate: our gorgeous boy came home 10 days later. My health visitor came round two days after, and that was the last I heard from her. No one ever answered when I rang – the number I’d been given for the community midwife always rang out. Covid meant that my personal support network was taken away, but I hadn’t been prepared for the professional support network to disappear too.

Then came the third lockdown of Christmas 2020. The limited connection I had with my family and friends was torn away, again. And with it went my ability to cope.

By the time February 2021 came around, I felt as if I had nothing left to give. One day, I sat on my bed knowing I had to get up and make the baby some lunch; he was about seven months old, but I couldn’t move. My whole body felt so heavy, I was a dead weight. I knew I had to go to the baby in the living room but I couldn’t get up. I just couldn’t face it any more.

The obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) that I had silently lived with since I was a teenager had become unmanageable. I knew I hadn’t been OK for a long time. I hadn’t managed to shrug off my depression because that’s not how it works. I glossed over it, but for the first time in my life it wasn’t working. The feeling was getting worse and it was interfering with my ability to be a mother; it was destroying my relationship with my partner; it was eating away at me.

I phoned my GP and explained that I thought I had postnatal depression. I was referred for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The sessions gave me the space to talk about my OCD for the first time, and opened my eyes to the fact that I have always struggled with anxiety, and that I don’t have to try to gloss over it. They taught me that I had to undo my way of thinking about stressful situations. I had to realise it wasn’t healthy, but harmful. Like any journey of self-learning, it’s a process.

Having a baby in a pandemic nearly broke me. I had to learn not only how to be a mother, but how to rebuild myself. But, on reflection, it’s not just me who could benefit from some rethinking. If we as a society are more open to the nuances and realities of pregnancy, women will put less pressure on themselves to live up to unrealistic expectations. They may then seek the help they need sooner.

Marshall’s GP referred her to IAPT for talking therapy and CBT. IAPT is a free NHS psychological therapy service offering support for common mental health difficulties such as depression and anxiety, OCD and post-traumatic stress disorder. A GP can refer you or you can refer yourself directly. Help is also available from the Association for Post Natal Illness.