When asked what was the best song he had ever written, the jazz great Duke Ellington famously quipped that it was one yet to come. He held out the promise of his future compositions being greater than his past and, perhaps more importantly, underlined a belief in lifelong endeavour.

Some artists simply get better with age. This may well be the case for Black British musicians in many genres, but whether they are recognised or not is a different matter. The cult of the “next big thing” often deflects attention from “dated” talent as it hits full maturity. Yet there are triumphs. As the following profiles reveal, many in the 50-plus age bracket experience struggle, sacrifice and achievement in equal measure.

Errollyn Wallen, 63

Born in Belize but raised in London, Wallen is an adventurous, mercurial composer who is known for her work in classical music. The great stylistic breadth of her output encompasses anything from pieces for solo piano to opera to songs such as Principia, which featured in the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Paralympics. Wallen founded Orchestra X, which has furthered the cause of diversity in the classical world, and her music has also been featured on Nasa’s STS 115 mission. She lives in a lighthouse on the north coast of Scotland.

“Having worked as a keyboard player in pop bands earlier in my career I saw how many brilliant Black artists were signed up then quickly spat out,” Wallen says. “My road to success in classical music has not been easy, but I have had such freedom to compose the music I want. Even though I have no record label I feel I have realised my potential in classical music in a way that would have been impossible in pop. The best thing about my career currently is that my music is performed live several times a week and seems to connect with people of all ages and backgrounds.”

Jean Toussaint, 61

The saxophonist upholds the far-reaching lineage of US expats who have made a significant impact on the British jazz scene. Toussaint arrived in the mid-80s as a sideman to the renowned drummer Art Blakey, settled in London and has since grown into an excellent leader in his own right, recording a string of fine solo albums that show his enviable skills as an improviser and composer. Furthermore, Toussaint has become a highly respected educator in London and Birmingham and over the years has mentored a number of significant contemporary musicians.

“Art [Blakey] was incredibly inspiring in every way and he taught us the importance of passing on our experiences to the younger generations of musicians,” Toussaint says. “This is one of the most important ways of ensuring that this great art form [jazz] continues to develop, thrive and live on. It’s a thankless task, but the help and encouragement that I personally received from the many legends that I was fortunate enough to encounter is the main thing that inspires me to continue. Also, on the practical side, once you’ve gotten to a certain level of development and attainment it’d be absolute madness to change career course.”

Carleen Anderson, 64

Born in Houston, Texas, but based in Britain since the early 90s, Anderson made her breakthrough as a member of Young Disciples, the Mercury prize nominees and leading lights of the acid jazz scene. She has since gone on to create a body of work that defies categorisation. Her sublime voice is matched by her ability as a composer and producer, as shown on her 2016 suite Cage Street Memorial: The Pilgrimage, with its beguiling mix of soul, gospel and electronics. She is currently working on Melior Opus Griot, a “futuristic opera” blending music, spoken word, dance and computerised sound.

“The entertainment industry shuns older women, and particularly women of African descent, due to advertising structures designed to steer appeal in a narrow direction,” says Anderson. “There are examples that defy these discriminatory, shortsighted policies. The light at the end of the tunnel is much brighter than it used to be, but still much further away than it should be. The best thing about this stage of my career is that I am liberated from the limits the music industry imposed on me, and now create to the fullness of my capabilities.”

Eska, 50

In the 2000s, Eska worked with jazz musicians such as Robert Mitchell and Jason Yarde but she has never been confined to a single genre. Her majestic voice suits the harmonic complexities of the aforementioned but, in a vaguely similar way to Anderson, she has proved to be remarkably experimental and eclectic, producing solo work that draws on anything from folk to electronica and sound collage. She has recently completed a film score and an opera, and has also debuted as a stage actor.

“In the music industry there seems to be some kind of visual prerequisite that I’ve never felt qualified for, like I’m not the right size, not the right age, I’m not the right shade of black,” says Eska of the barriers she has faced as an artist. “The best thing about this stage of my career is that I feel I have a sense of what it is that I want to achieve, what my goals are in terms of professional development. I’m the curator of my own life. There would be more output from me if there was a bit more support. I choose to work on things I feel will be significant in defining the artist that I am.”

Keith Waithe, 72

Whether leading one of his many bands, such as Macusi players, or performing solo, this Sussex-based Guyanese flautist has daredevil virtuosity and often combines intricate solos with outre vocal effects that hark back to virtuosic performers such as Rahsaan Roland Kirk. Since the 80s, Waithe has performed at jazz and folk festivals around the world, presented major projects on African and Black diaspora history and given opportunities to significant artists at the early stage of their careers, such as Robert Mitchell. Waithe has also collaborated with many great poets, from Jean “Binta” Breeze and Kwame Dawes to Patience Agbabi and John Agard.

“The best thing about this stage of my career is not having to hustle to make a living and waiting to be booked for the only guaranteed pay cheque of Black History Month!” says Waithe, voicing a frustration also felt by many of his peers. “I enjoy the opportunity to work with young artists like Loyle Carner and I have the freedom to go at my own pace, and be inspired by the beauty of nature here on the South Downs, which is reminiscent of the lush greenery of the rainforest in Guyana.”

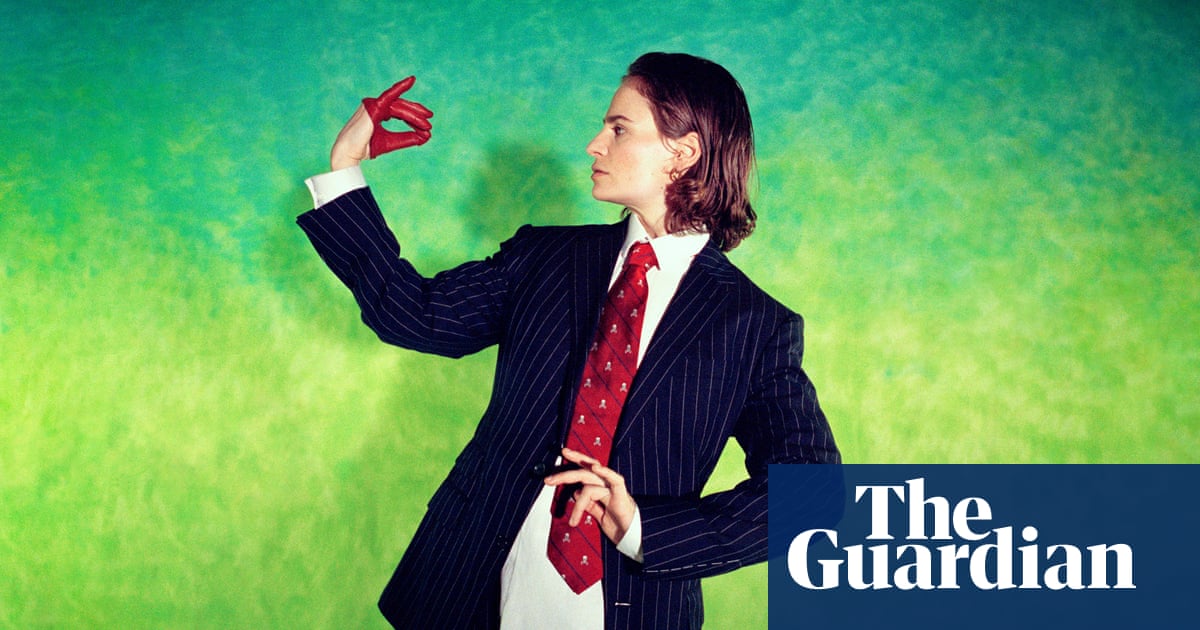

Omar Lye-Fook, 53

One of the defining artists in black British music of the past three decades, Omar enjoyed major commercial success in the early 90s with There’s Nothing Like This. A hugely talented singer and multi-instrumentalist, he has always worked right on the borders of soul, jazz, reggae and Latin music, and his writing has been remarkably consistent over eight albums. He is currently working on his ninth, Brighter the Days.

“I think about the legacy thing, and it’s humbling to know that stuff I’ve created over the years is still here and it’s lasted,” says Omar of his artistic journey. “When I first started making music … my first single, I hated it with a passion. I decided that any music I was gonna make after that, it had to be good enough to last, because you’re gonna be singing this thing for the rest of your life. It can either be a ball and chain round your ankle, or something that you enjoy performing, and I hope people enjoy listening as much as I do performing. The kind of music I’ve been trying to make is stuff that will be played 25 or 30 years from now.”

Pat Thomas, 61

A virtuoso pianist who is also a wizard with synths and live electronics, Thomas is a central figure in British and European improvised music. In the early stage of his career he worked with the guitar pioneer Derek Bailey and has developed a highly individual approach to the keyboard that produces unconventional harmonies and rhythmic figures regardless of whether he is playing original pieces or interpreting the work of seminal figures such as Duke Ellington. Thomas is also part of Black Top, a duo formed with Orphy Robinson that invites players of all ages to take part in purely improvised sessions, such as, recently, the young Birmingham saxophonist Xhosa Cole.

“Different generations bring different approaches to phrasing and rhythm and it makes an amazing mix of sounds that you wouldn’t hear if all were from the same generation,” says Thomas of bands in which there can be a 40-year age gap between older and younger players. “The best thing about being a mature musician is knowing that there are still things to learn. With experience you know how to start and finish and make the music breathe.”