25 May 2020. Minneapolis, Minnesota. George Floyd is leaving a shop after paying for a packet of cigarettes with a fake $20 bill. In line with the workplace’s policy, a member of staff has called the police. George is arrested, handcuffed, and led to the police car. It’s at this point that he begins to display severe distress. Police officers restrain him, and one of them takes up a position on top of him, placing his knee on top of George’s neck. George protests and says he can’t breathe, but he receives no reprieve from the officer killing him. Then, he seems to accept his fate. “Mom, love you,” he says. “Tell my kids I love them.” Soon after, he stops talking. It is only when paramedics arrive that the knee is lifted. George’s body is put on to a stretcher, his limbs loose and floppy. An hour later, he is declared dead at a hospital nearby.

On 26 May, video footage of the murder, filmed by a teenage bystander, is uploaded to social media. Protesters gather in Louisville, Minneapolis and Glynn County, united by the same cry: Black Lives Matter. The protests quickly spread across the United States.

In Britain, we were in the midst of the first Covid lockdown. News of the Black Lives Matter protests was the only thing that cut through three months of almost non-stop coronavirus coverage, and with it came an undeniable sense of urgency. People were sharing resources – books, podcasts, films, documentaries – to help understand the moment they found themselves in. Some people had curated anti-racist reading lists, and were distributing them online. My social media accounts were tagged and mentioned repeatedly by readers recommending my book Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race.

By mid-June, it had rocketed up the bestseller charts, not just in Britain, but in the United States too. At any other time, the bestseller charts simply reflect the publishing industry’s commercial successes. But this time, they seemed to signal a fundamental change in wider society.

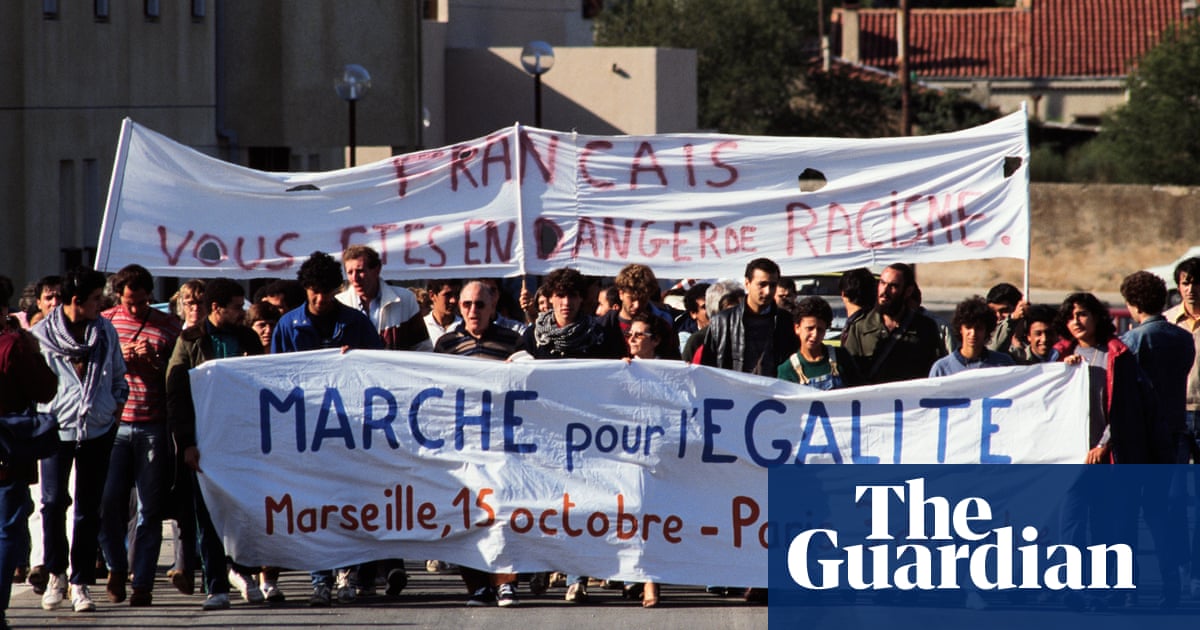

The mainstream understanding of racism was shifting beneath our feet, and it felt transformative. In the patch of London I’d lived in for five years, I saw Black Lives Matter signs plastered in my neighbours’ windows. On the streets, crowds of people put Covid regulations aside as they gathered in city centres to mourn the dead and fight for the living. I had been going to protests since I was 19, and I knew something was different about this moment. The general public – the very same people that activists had laboured to reach, bickered and fought among ourselves to persuade – were already on side. And in Bristol, a port city in south-west England, an action was about to take place that would reverberate across the world.

Rhian Graham woke up on the morning of Sunday 7 June with a strong desire to make it to Bristol’s Black Lives Matter march. Prior to the pandemic, Rhian had worked in events and stage management, rigging lights with ropes on stages and sets. She hadn’t attended many protests before and did not consider herself an activist. But in the days after footage of George Floyd’s murder had captured the world’s attention, she began to have conversations about racism with the people around her. Rhian downloaded the audiobook of Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, and started listening. “I just really felt like I had to go to that protest and show solidarity, and this idea of possibly being able to pull the statue down had arisen. I’m one of those people that’s eager to help.” She references the skills she developed in her pre-pandemic job, setting up lighting. “I’m a rigger, I’ve got rope, I can tie knots … maybe we should try that.”

We are in Bristol, more than a year and a half later. Rhian and her partner are helping me retread the route of the march. When she arrived at the rally, 10,000 people had gathered on College Green. “There was so much passion and sort of a furious need to be in the streets that day,” she tells me.

From College Green the crowd proceeded through the streets of the city centre. Following the route together, we pass a statue of Queen Victoria. “If it was mindless vandalism, that statue would have probably been the first one to get,” Rhian’s partner quips. We walk down St Augustine’s Parade, passing another statue in the pedestrianised city centre. Neptune, god of the sea, wields his sceptre authoritatively. In just a few steps we reach the plinth that once held a statue of slave trader Edward Colston.

And so, on Sunday 7 June 2020, as the march moved through the city centre, Rhian made a beeline for the statue. She was accompanied by two friends, Sage Willoughby and Milo Ponsford. “I didn’t know Milo was going to have a rope,” she tells me when we meet. “Milo didn’t know I was gonna have a rope.” The night before, she had visited Milo’s workshop. “We chatted about it, about the concept of laying down the statue, but there wasn’t, like, a set plan; I didn’t know how much he’d committed to the idea.”

Rhian, Milo and Sage positioned themselves in front of the statue, which two people had already climbed up, and pulled ropes out of their bags. “Simultaneously, I think we all knew what was gonna happen,” Rhian says. Video footage of the day shows Rhian and Milo in a small crowd, tugging at the ropes tied around the statue. The base of the statue yielded, and the figure of Colston leaned forwards before toppling to the ground. “It all happened within about two and a half minutes,” she says. She gestures to the dent in the pavement where the statue initially struck the ground. “That impact on the floor, just, like, reverberated out from the city.”

On this particular Black Lives Matter march, prompted by the brutal murder of George Floyd, the link between the viral video footage of his death and a centuries-old British slave trader was clear. As an African American man, Floyd was likely descended from slaves. It is certain that, like all African Americans, he lived a life, and died a death, that was shaped harshly by the structural racism endemic in US society. His present was the result of hundreds of years of discrimination, with a legacy rooted squarely in the slave trade.

“The feeling of pulling down that statue was really a lesson in my own agency in the world, and realising that I can have an effect on my surroundings and can have a say and use my voice,” Rhian says. Protesters immediately set upon it, jumping up and down on the statue, beating it and kneeling on its neck. Rhian peeled away from the crowd again and headed towards Castle Park, where the main march was planned to end, while the protesters rolled the statue towards the Floating Harbour. It was there that it was launched into the docks.

That afternoon made headlines around the world. Condemnation from Britain’s political leaders arrived quickly. A statement by Boris Johnson’s spokesperson called the toppling a “criminal act”, but also said that he understood “the strength of feeling”. Home secretary Priti Patel was much less measured, calling the act “disgraceful”, and referring to Rhian and those around her as a “mob”. Labour leader Keir Starmer said pulling down the statue was “completely wrong”.

But the moment could not easily be argued away or dismissed. Bristol’s statue-toppling existed not in isolation, but in the midst of a global uprising against racism. Across Britain, over the course of a week, protests and rallies in favour of the inherent worth of Black lives fundamentally challenged the existing consensus. The response was not just political: it shook the foundations of workplaces, corporate offices, schools, local authorities and family dinner tables. It changed how friends and acquaintances related to one another. It intensified a social pressure to care, to know, and to understand.

I used to believe that making the case for a just society would be met with enthusiasm, not vitriol. But anywhere the cause of anti-racism has convinced enough of the general populace, a cruel defence of the status quo has quickly followed. What exactly needs to be preserved evades me. I am still unsure of what might be lost if some Black authors are added to a curriculum, or if a city adds some of the uglier parts of its history to a plaque celebrating the pretty bits. The backlash to the incredible groundswell of young people searching for more British history – history that just happens to look at areas we don’t examine too closely in school – amazes me. I’ve watched aghast as conservatives deride them for their inclination towards critical thinking and curiosity, their searching for context to ground today’s social issues. The accusations of censoriousness don’t make sense to me. They are seeking to add more context, not to erase what is already known.

What has become clear is that there are sections of Britain that fear the upending of the social order. In the last five years, it feels like so much has shifted. While the old guard still occupy much of the space, who gets to influence the public sphere has changed fundamentally. Seven years ago I was working part-time in a pub for £60 a week. When I signed the deal for my book, I was not the product of a private school, or someone who had been bred for power. I wondered if the pushback against people like me was because I should not have been influencing public debate.

In December 2021, Rhian Graham stood up in Bristol crown court and told the jury that reading Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race had been a turning point for her. She was giving evidence in her defence after entering a plea of not guilty at Bristol magistrates’ court. She was cleared of all charges by a jury on 5 January 2022.

Rhian’s defence barristers put forward a convincing argument: they said that the statue’s continued presence, despite decades of opposition from residents, was tantamount to public indecency. They used the wording of the plaque – “erected by the citizens of Bristol” – to argue that the defendants truly believed that the statue belonged to the city’s residents, and that years of opposition to the statue implored them, as citizens of Bristol, to bring it down.

When I got home from my trip to see Rhian, I picked up a copy of my book, flicking through the pages to remind myself of the final lines. I had written: “If you are disgusted by what you see, and if you feel the fire coursing through your veins, then it’s up to you. You don’t have to be the leader of a global movement or a household name.” I thought about the long stretch of time that had passed since I wrote those lines hunched over a cold kitchen table, chilblains on my fingers from trying to save money on bills. I thought about all the people I’d met over the last five years, how many had reached out, in writing or in person, to tell me how they were trying to change their corner of the world.

I thought about the movement that this book came from, the movement it helped fuel, the people it connected. There is no such thing as a lone genius, despite our society’s proclivity to train its laser focus on a single successful person. Over the years, I came to hate being regarded in this way. The success of this book is still not something I’m willing to claim in my personal life. I see it as something separate from me, something that belongs to its readers. I ended the original foreword with the words “I hope you use it as a tool”, and I am glad that has come true. It was an extension of my years of reading theory, engaging in the feminist internet, waving placards at marches and going to activist meetings. It was a culmination of conversations, of challenging and being challenged. It was often in community conflict that my understanding of the world was honed and expanded. I thought about the piece of writing that spawned the book: “I’m no longer engaging with white people on the topic of race. Not all white people, just the vast majority who refuse to accept the legitimacy of structural racism and its symptoms.” In making my personal decision public, that piece of writing had not only served its initial purpose as a way to work out my thoughts and feelings, it had also functioned as an invitation, drawing more people into the conversation. It’s in community that you find yourself, and I couldn’t have completed that piece of writing without it.

I could not allow myself to be happy when Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race topped the UK book charts. The conditions that milestone came from were simply too dire. The streets were full of mourning, grief and rage. With distance, I can see that despite this achievement emerging from a time of crisis, it was still an achievement – not just for me, but for a movement that has long been marginalised and maligned. There is a bad-faith characterisation of anti-racism, one that tries to position anti-racist thinking and thinkers as a new “establishment”, even though the opposite is true. It edits no national newspapers, write no laws, and polices no streets.

“The bottom line is this,” James Baldwin told the New York Times in 1979. “You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can’t, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world. In some way, your aspirations and concern for a single man in fact do begin to change the world. The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter, even by a millimetre, the way a person looks or people look at reality, then you can change it.”

This is an edited extract from a new and updated edition of Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge, published by Bloomsbury in paperback (£9.99). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.