Born in 1964, David Baddiel is a writer, comedian and TV personality. He left Cambridge University with a double first and a burgeoning comedy career: going on to write on shows such as Spitting Image and The Mary Whitehouse Experience, teaming up first with Robert Newman for stadium-slaying comedy duo Newman and Baddiel, and then Frank Skinner, with whom he became a TV fixture with Fantasy Football League and the hit single Three Lions. He has written numerous novels, autobiographies and screenplays, and is a bestselling children’s author. His latest, Virtually Christmas, is out now. Baddiel lives in London with his wife, actor Morwenna Banks, and their two children.

Aged seven, I look very sweet. I was getting a headshot done for my school, North West London Jewish Day School, and as my hair is naturally really curly, I’m wondering if it was straightened by my mum.

Back then, life was fine: mundane, lower-middle class, and about to be beset by certain things, including my mum’s affair and my dad’s redundancy from [research chemist] Unilever, which happened very soon after this photo was taken.

While my school was Orthodox, my family was not straightforwardly so: my mum was born in Nazi Germany and her parents had got out and were reformed Jews, so we used to do quite big Passovers and Rosh Hashanahs. However, my dad was a dyed-in-the-wool atheist. That day I’d probably gone to school having eaten bacon and eggs for breakfast, but I was then wearing koppels and yarmulkes like in this photo, and sometimes a tzitzit [a tasselled ceremonial garment].

My part of London, NW10, was extremely rough in the 1970s, and Britain was, even more than now, on the brink of collapse. I remember, as a Jew, feeling quite frightened because there were lots of skinheads. The National Front was quite big. Going into school, you occasionally had people throwing stuff or chanting at you. Having said that, I did enjoy school and my reports were generally quite complimentary. At 11, I was part of a team who won a national quiz for Jewish schools called the JNF [Jewish National Fund] quiz, and I spent my £50 book voucher on a biography of [the first prime minister of Israel] David Ben-Gurion that I was definitely never going to read.

When my daughter Dolly left school, I noticed there was an element of glamour to the ceremony – it was an experience not unlike the Oscars with lots of emotional singing and speeches and poetry. My memory of leaving school is one of our form teachers, Mr Cohen, basically saying: “Some of you are going to Jewish schools after this, which is great, but for the ones who are going to non-Jewish schools, what you should know is there will be someone at that school who doesn’t like Jews.” That was his inspirational speech. And he was absolutely right, of course. I had a bit of anxiety about being thrust out into the non-Jewish world. But I realised even back then that although I have no belief in a supernatural being of any sort, I feel my Jewish cultural identity and ethnic identity very deeply.

By the time I went to secondary school, I was doing comedy – being incredibly naughty and enjoying making people laugh. When I was 16, we had to put on a show at lunchtime, and it was always rubbish, so that year I just made sketches about the teachers who were really horrible – the ones everyone hated. I thought it was funny, but naturally the show was stopped and I got into a lot of trouble. I thought I might get expelled but thankfully they didn’t because that school, Haberdashers’ in Elstree, was keen on getting as many people into Cambridge as possible, which I eventually did.

When I was growing up, I was very much looking to my brother, Ivor, and maybe a couple other older friends of mine to ask: “Who should I be?” The reason I’m a Chelsea fan is that when he was eight, and I was six, Chelsea won the FA Cup: Ivor got excited, and I just copied Ivor. And actually, even now when I see myself on TV I think my mannerisms are really quite like Ivor’s. Siblings are unbelievably important, especially in a world like mine, where parenting was not a word understood by my mum and dad. They were basically just living their own mad lives – my dad was unemployed and angry, while my mum was distracted by her passionate affair. So I was parented by my brother.

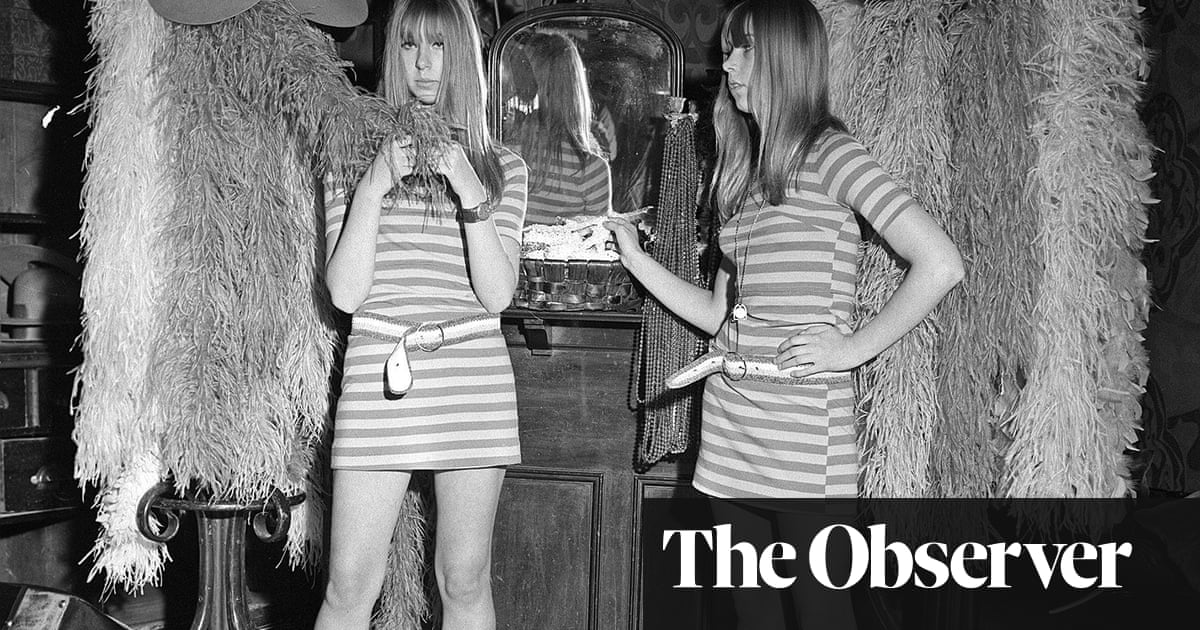

Similarities to my brother aside, anyone who knows me well would say that I am wearily, exhaustingly myself. On stage and on TV, I was interested in trying to be as natural as possible, because I don’t like pretending to be someone else in real life. During my many years of psychotherapy, I have questioned whether it’s a response to my mother’s affair. She was very much a bored woman who lived in Cricklewood in the 1970s. She was born in Königsberg [the Prussian city, now Kaliningrad, Russia] to a family who had been very wealthy, and then lost everything. Then suddenly, having set up this new life with three children, she became the golfing memorabilia queen of north London. Her whole life became about golfing memorabilia – it was all over the house – because she was having a relationship with a golfing memorabilia salesman. I wonder if her desperate yearning for something a bit more glamorous, like golf, was to do with that lost narrative from her childhood. And I also wonder if my own need to be “authentic” is a reaction to the thought: “I do hope that never happens to me!”

While there was a sadness to my childhood, I am very keen to say I am happy with who I am now. I did love my parents, I do love my parents, even though they were on some levels, fucked up. But the celebration of their damage is part of my truth. That’s a pretentious sentence, but I have decided that if you are happy with who you are, you have to celebrate how you got there, even if it involves your mum turning the whole house into a golfing palace in honour of an affair, and your dad being unemployed for two years and then being furious with you all the time. This – that – is who I am.

I didn’t come from a privileged or unprivileged background. But I made it into comedy. When I look at that kid in the photo, I think: this boy doesn’t know it’s going to play out. It may be grim now, but comedy is going to come to the rescue.