The film Georgy Girl, starring Lynn Redgrave and based on a book by Margaret Forster, was released in 1966. The title song, sung by the Australian group the Seekers, had an upbeat beginning: “Hey there, Georgy Girl, swinging down the street so fancy-free.” Then it got a touch darker. “Nobody you meet could ever see the loneliness there, inside you.” Followed by the crucial question: “Is it the clothes you wear?”

The answer was definitely “yes” if you were a teenager under your mother’s thumb. In those circumstances, you might be dressed liked a middle-aged matron, sensible cardigans, “good” dresses and an armoury of underwear capable of fighting off even the toughest enemy invasion. Alternatively, you might have been more fortunate. You might have been introduced to Biba.

On 22 March, an exhibition titled The Biba Story: 1964-1975 opens at the Fashion and Textile Museum in Bermondsey, south London. Hopefully, it will capture the clothes and range of products, from baked beans in the trademark Biba art deco colours of black and gold to “sludgy” makeup – launched at a time when lipsticks came in 25 shades of pink – and all the excesses of glam rock, beloved by Freddie Mercury and David Bowie.

Biba’s founder, Barbara Hulanicki, turned shopping into “an experience”, six decades before anyone else. The 1950s had been dreary. As the journalist Lynn Barber once said, the most exciting event of that decade was the launch of Birds Eye roast beef frozen dinner for one. Then came Biba.

Aged 16, I was still at school, working as a waitress at weekends. Biba was not only affordable, it was wholly, entirely and thrillingly different from anything in my mother’s wardrobe and, initially, every Biba purchase I made horrified her, which added to the satisfaction. “Call that scrap of cloth a dress?” alternated with, “Are you going out looking like that?” Yes and yes.

In May 1964, Felicity Green, a doyen of Fleet Street, had run a fashion feature in the Daily Mirror in which a pink gingham mini shift with a matching head scarf, made by Biba, was offered for 25 shillings. Seventeen thousand enthusiasts sent in postal orders and, like me, kept coming back for more, at first from Biba’s postal boutique and then from the magic that were her shops.

The exhibition is curated by Martine Pel, who has worked with Polish-born Hulanicki, now aged 87, several times before. They have also co-written The Biba Story, to be published in September. Hulanicki was a successful fashion illustrator when she and her husband, Stephen Fitz-Simon, “Fitz”, an advertising executive, decided to produce their own range of clothes. They named the company Biba, after Hulanicki’s younger sister. In her autobiography, From A to Biba, she says one critic said, “it sounded like a charlady’s daughter … so we felt we had got it right.” Presciently, she was designing for the street.

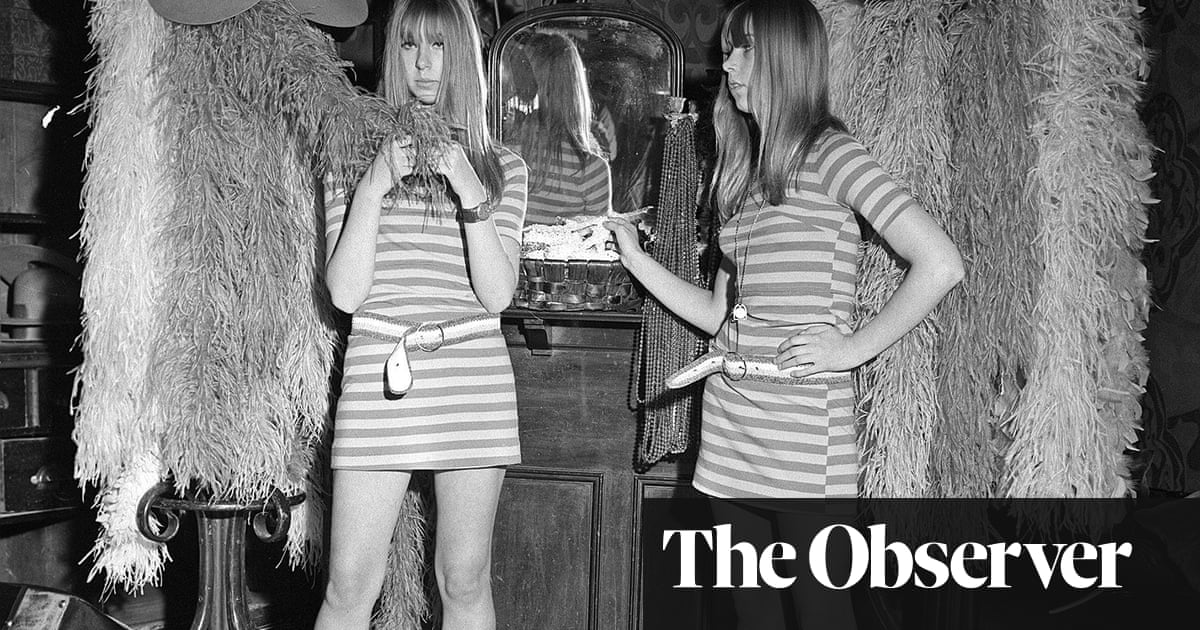

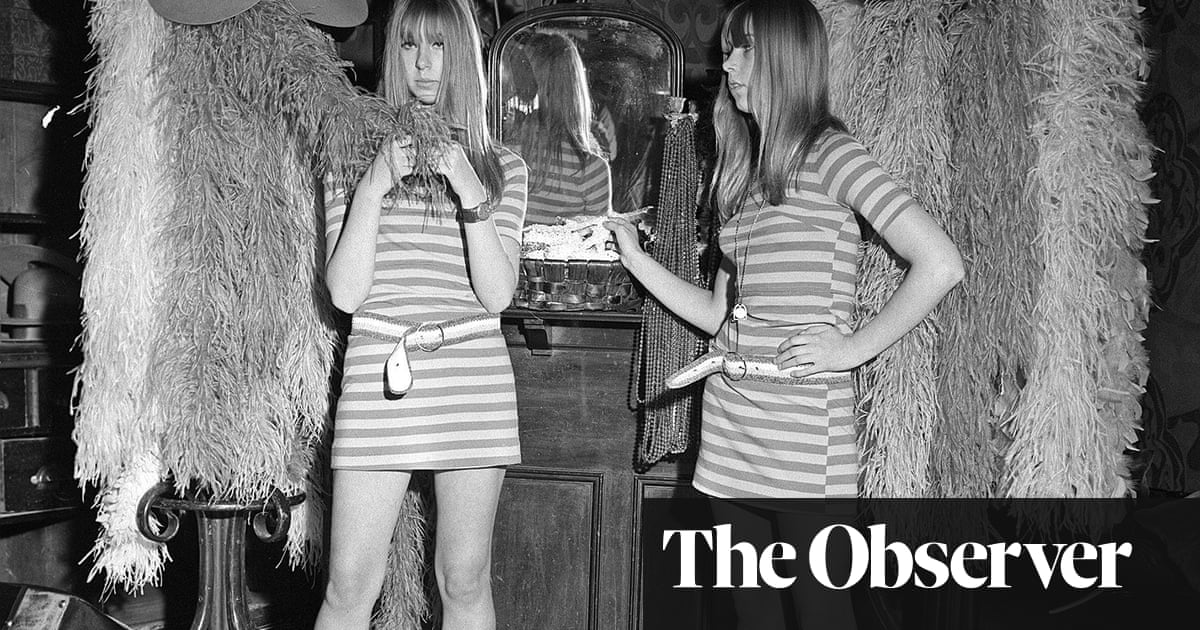

Hulanicki said the “dolly” Biba girl had, “a skinny body with long asparagus legs … and quite flat-chested.” Every incarnation of Biba, from the tiny chemist shop in Abingdon Road where it all began – navy-blue walls, black and white floor – to the final magnificent seven floors of the former Derry and Toms in Kensington High Street where it abruptly ended, was as dark as Hades, made even gloomier by Biba’s favourite hues – plum, prune, mulberry, rust, maroon – “blackout colours” in my mother’s opinion. Shapes and sizes of fellow customers were difficult to see, but you could hear the groans of girls trying to squeeze themselves into clothes designed mainly for waifs.

Mary Quant had opened her first shop, Bazaar, in Kings Road, in 1955. Quant said that in her boutiques there were “duchesses jostling with typists”. A Quant pinafore dress in 1960 was priced at 17 guineas, three times a typist’s wage. Biba aimed for the young market – £3 bought a dress in the early days, £2 a blouse. Biba was not throwaway fashion, it was built to last. If, that is, an item survived a mauling in the communal changing room.

It was always mayhem, 100,000 customers a week at the peak. Piles of clothes on the floor, girls scrabbling to find the only item left in a particular style. The assistants, who definitely did not consider that they were there to assist, were the Biba brand brought to life; false eyelashes, minidresses, boots, floppy hats, feather boas, goddesses. They were to be looked at, not pestered. But I did pester my mother.

In postwar Britain, three-quarters of English women were married by 25, including my mother. Her generation went from school age directly to middle age, the freedom of youth erased by war. My mother was badly wounded, aged 18, refusing to hit the ground in a new coat during a raid and twice the family home was destroyed by bombs. Such turmoil meant she placed a high value on stability, respectability and security. Especially my respectability and security. And that’s where the battleground lay – until Biba negotiated a truce.

My mother had left school at 14 and trained as a tailor, making men’s suits. I pestered her until she finally “volunteered” to duplicate Biba; scalloped hems, empire lines, floral suits, she could do it all. It dawned on me that my mother wasn’t some kind of ancient (she was only in her 40s) to my modern. Biba had provided a bridge.

In 1975, Barbara Hulanicki OBE fell out with the board and parted company with the business, losing the name. It has been reincarnated several times. Biba now resides uncomfortably in the House of Fraser. “This is not the same time,” Hulanicki has said. “So it cannot be the same thing.” Sadly, so true but the memories are golden.