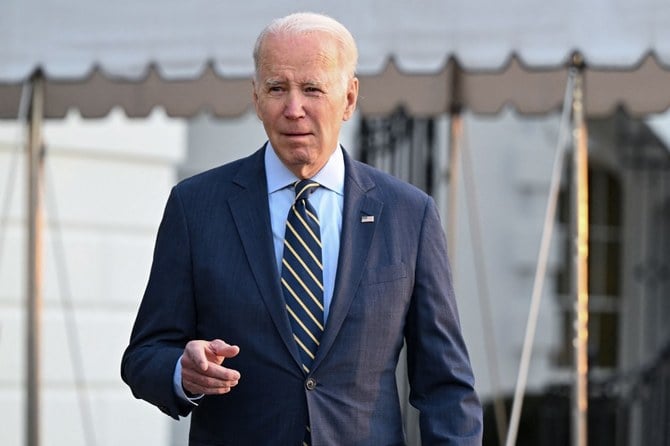

President Joe Biden is now halfway through his four-year presidential term, providing an opportunity to assess progress on his foreign policy priorities.

In many ways, Biden’s first year in office, in 2021, was spent trying to undo what he saw as the damage caused by former President Donald Trump to the US’ reputation and foreign relations. He also withdrew US forces from Afghanistan, facing criticism about the subsequent chaos and Taliban takeover.

Biden’s foreign policy officials hoped to shift from crisis management and rebuilding to proactively pursuing more strategic priorities in 2022, including relations with China, climate change and a nuclear deal with Iran. All US presidents must face the reality that events beyond their control will occur that require them to refocus attention.

Fortunately, Biden and his team were relatively well prepared for the major event that upended global politics in 2022: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. US officials had warned in advance that Russia intended to make such a move, giving the administration time to engage with European allies and Ukraine. When Russia proved that US warnings were correct, it bolstered Washington’s reputation.

Russia’s war in Ukraine fits into Biden’s existing view of the world and his framework for foreign policy. From the beginning of his presidency, Biden embraced the idea of a “contest between democracy and autocracy,” as he said in a speech to the UN in September. The war between Ukraine and Russia matched the image of a democratic country defending itself against an aggressive autocratic state. Furthermore, Biden had emphasized the importance of international rules and norms, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a clear violation of the norm of sovereignty that underlies the UN and the global order.

When Russia proved that US warnings on Ukraine were correct, it bolstered Washington’s reputation

Kerry Boyd Anderson

The White House received much praise for its handling of the war in Ukraine, particularly compared to the widespread criticism over the withdrawal from Afghanistan. Crucially, Biden chose to avoid direct military involvement and has been clear that the US will not send troops to Ukraine; this decision is critical to avoid escalating to a far scarier war between the nuclear-armed US and Russia. At the same time, Washington is providing significant military, economic and humanitarian support to Ukraine — providing far more aid than any other country.

In addition to direct support for Kyiv, Washington led Europe in uniting behind Ukraine. The war and Western countries’ responses have strengthened NATO, with both Sweden and Finland now asking to join. The US has imposed additional sanctions on Russia and encouraged European countries to pass truly painful sanctions and cut many trade links with Moscow. Internationally, Washington has worked to gain support for Ukraine. Biden’s administration has also responded to the war’s many secondary effects; the US government has supported the Black Sea grain deal and earmarked funds to assist countries in addressing the war’s impacts, including food insecurity.

The war in Ukraine consumed much of the administration’s foreign policy resources in the last year, taking resources away from some other priorities. Nonetheless, China remains a top concern. Many national security analysts see China as a bigger and more complex challenge than Russia.

Given China’s role in the global economy and the necessity of working with Beijing on climate issues, Biden’s team knows that a complete break with Beijing is not a realistic option. However, Biden has taken a relatively hard line on China, including keeping many of the tariffs imposed under Trump. While Biden has declared an ongoing commitment to “our One China policy,” he also said in 2021 and again in 2022 that the US would defend Taiwan if China were to attack. Biden and Congress took additional steps this year to limit technology transfers to China and hinder its ability to dominate technology supply chains. And the US military has been clear that it sees China as its main challenge.

Meanwhile, Biden continues to prioritize climate change, attending COP26 and COP27 and passing major legislation to help decrease US emissions. He also continues to work on repairing relations with European states; in December, he put on his first official state dinner, hosting France’s President Emmanuel Macron.

Biden’s administration has achieved little on one of its initial top priorities: Renewing a nuclear deal with Iran. Hopes rose over the summer, but Iran added new demands and negotiations appeared to fizzle out. Around the same time, the current protest movement in Iran began. US officials have expressed support for the protests and suggested that this is not the right time to push for a nuclear deal.

In 2023, domestic politics will constrain Biden’s foreign policy to some degree. Democrats will remain in charge of the most important legislative body for foreign policy, the Senate. However, Republicans will control the House of Representatives and they might reduce funds for Ukraine, hold hearings into the Afghanistan withdrawal and generally complicate Biden’s efforts. Furthermore, with Trump running again for president, Biden may struggle to persuade allies and rivals that the Trump era is truly over.

Supporting Ukraine, maintaining European unity, managing relations with China and addressing climate change will remain top priorities for the second half of Biden’s presidential term. Washington will keep a close eye on events in Iran. Europe and the US will continue to express support for a return to a nuclear deal, but the realities of domestic politics in the US and Iran leave little space or incentives for compromise.

Of course, there are many simmering areas that could erupt into problems that demand Washington’s attention. US officials can try to choose their priorities, but often they must respond to real-world events.

Kerry Boyd Anderson is a writer and political risk consultant with more than 18 years of experience as a professional analyst of international security issues and Middle East political and business risk. Her previous positions include deputy director for advisory with Oxford Analytica. Twitter: @KBAresearch