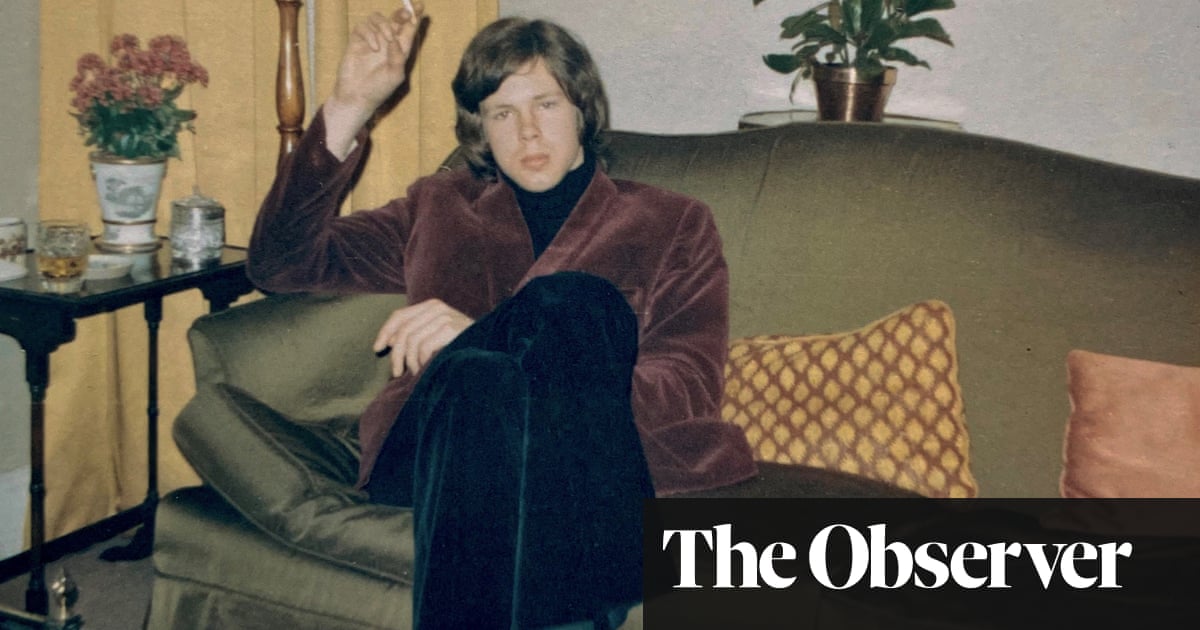

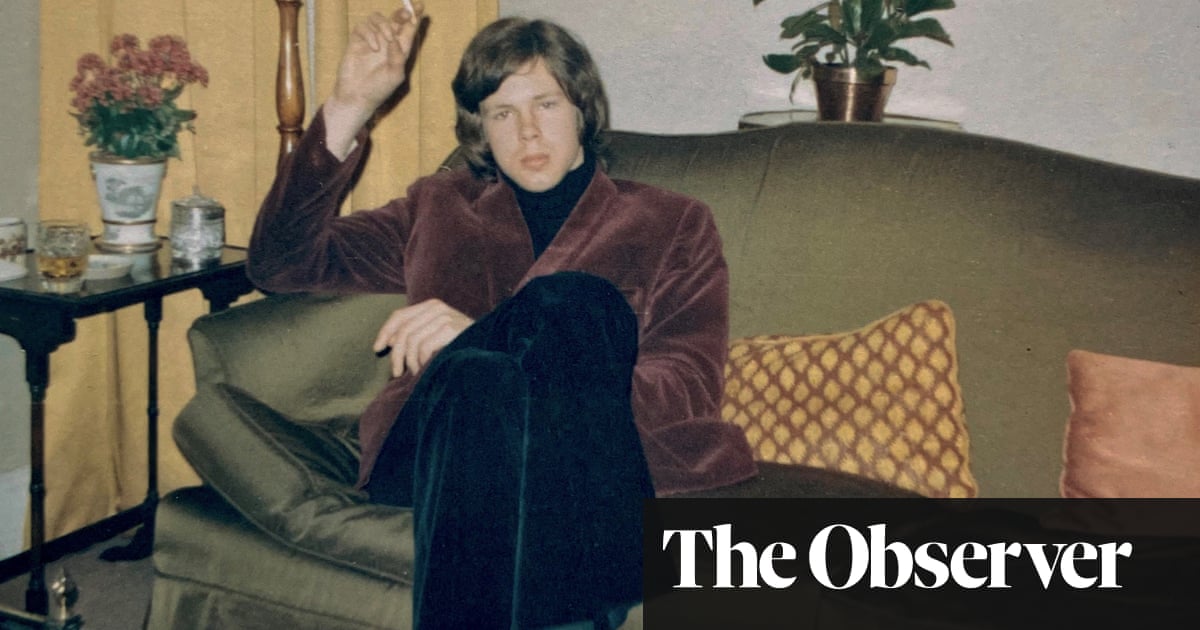

When the cult singer-songwriter Nick Drake’s third album, Pink Moon, was released in 1972 many of his friends were horrified. Now held to be a stone-cold classic, it is a spare, beautiful sequence of songs, many of which lay bare its 24-year-old author’s inner tumult. Drake’s two previous albums, Five Leaves Left (1969) and Bryter Layter (1971), had sold poorly. Although he was an English singer-guitarist whose unconventional tunings and numinous lyrics set him apart, even in a crowded folk revival field, a chasm had opened up between the promise of his talent and his meagre public profile.

Now, Drake is revered as a depressed romantic too fragile for the world. The Cure took their name from one of his songs. In the 80s, artists as diverse as Kate Bush and the Dream Academy cited him as an influence. Volkswagen used Pink Moon’s title track in an ad in 1999, prompting a fresh upsurge of interest in his oblique pastorals.

Pink Moon was the product of a period of intense, secretive songwriting, during which the singer’s behaviour became more erratic and his mental health deteriorated, much to the anguish of family and friends. It was a mark of the regard in which he was held by associates that the album was recorded with little warning, late at night, exactly as Drake prescribed by engineer/producer John Wood with no external input (the previous two LPs featured arrangements).

Drake handed over a recording of Pink Moon to Island Records’ bewildered boss Chris Blackwell, who had not been expecting it, before going dark again. Blackwell ploughed ahead with his most mysterious charge’s release, even though Drake had no interest in artwork or press. There was little hope of the erratic, retiring musician touring. Pink Moon didn’t sell much either.

Drake is now ensconced in myth as a doomed poet whose life ended at 26 through an overdose of antidepressants. Previous biographies and documentaries have given thorough accounts of his life and work, including one in 2014 by his sister, Gabrielle Drake, the actor. The work of their mother, Molly Drake, has been folded into the story. Her son had grown up to the sound of Molly composing songs at the piano; there are resonances in their bodies of work.

Richard Morton Jack’s authoritative doorstop is, though, the definitive word on Drake, insofar as the story of a deeply inward-facing man can be told by others. It builds on everything that has gone before and adds so much detail it can seem, at times, overwhelming. Although a foreword by Gabrielle Drake maintains that this is not an authorised work, she provided Drake’s own papers, her father’s diary and gave her blessing for everyone around Drake to contribute. Patrick Humphries, who published a biography of Drake in 1997, even handed over his own archive. There is something of Mark Lewisohn’s approach to the Beatles here: no childhood friend or university contemporary is left un-interviewed. There are a great many school reports. Drake’s guitars are reverently documented.

The outcome of this forensic but always eloquent account is two-fold. The first half of the book sets out to establish just how normal and, indeed, biddable and cheerful Drake was as a child. Born in Rangoon, he lived a life of genteel privilege in Warwickshire from the age of two where his parents, “old Burma hands” in the colonial parlance, doted on him and his sister. Their Karen nanny, Naw Rosie Paw Tun, acted as third parent (the Karen people originate along the Thailand-Myanmar border and remain in conflict with the Burman majority in Myanmar). Although Drake disdained sports, he was athletic and could be persuaded to join in; he got up to high jinks at Marlborough College and, later, Cambridge, where he gravitated towards other “heads” into the burgeoning 60s music scene. Most agree that he could be detached or preoccupied with his own interests. But there was little in his early years that predestined a life of artistic torment.

Among the many interviewees, a couple of material witness accounts are absent. The family’s housekeeper, Naw Ma Naw, died in 1988 and so could not have been consulted by Morton Jack. Her aunt, Naw Rosie Paw Tun, the Drakes’ long-serving nanny, is also presumably long gone.

Even so, it is a small shortcoming in this assiduously researched work that Morton Jack follows the lead of this largely upper-middle-class cast in reporting that Tun and Naw were part of the family, rather than servants, and yet their thoughts on Drake and his end have not been recorded or conjectured. The book is full of public schoolboys weighing in on whether the singer was odd. Naw was the one to discover Drake’s body on a November morning in 1974. She was reportedly the last to hear him alive, moving about around 5.30am. Her thoughts and feelings can be imagined, but are not known.

In an interview with Uncut magazine, Morton Jack makes plain there are no shocking revelations in his work. Drake’s lack of interest in the opposite sex has led some to speculate whether he was gay; Morton Jack finds no evidence, and records his proposal of marriage to a friend, Sophia Ryde. Drugs might have explained Drake’s decline. But although much dope was smoked – and it remains plausible that the singer’s cannabis consumption might have precipitated a form of psychosis – Morton Jack concludes that he almost certainly wasn’t using anything harder.

The last third of the book is difficult to read – through no fault of the author’s, but because Drake’s final months are chronicled almost day by painful day. There is no ending other than that foretold.

Drawing on the diary Rodney Drake kept when his son moved back to the family home at Far Leys in Warwickshire, Morton Jack bears witness to Drake’s alarming unravelling: all the psychiatric interventions, all the missed pills, all the false dawns. Drake smashed things up, he would disappear for days, go to Paris ostensibly to write an album for Françoise Hardy, come straight back. He would take long drives, then abandon his car when it ran out of petrol. Often he was unable to speak. Astoundingly, he considered joining the army and accepted a job in IT, but never took it up.

Everyone around him tried to help; from time to time, some did, leading to more heartbreak when Drake relapsed. The diagnosis was “simple” schizophrenia. But in a moving letter to Rodney, one of the doctors who saw Drake implored his devoted parents not to blame themselves. “People who have studied this illness all their lives have no better understanding of patients than you had of Nick,” he wrote. This book is illuminating, but Drake himself remains painfully unknowable.