Richard T Kelly writes the kind of chunky panoramic sagas thought to have gone out with the ark. Crusaders (2008) took place in his native Newcastle upon Tyne ahead of New Labour’s rise to power; The Knives (2016), more thrillerish, offered a non-demonising portrait of a beleaguered Tory home secretary in 2010. His quietly stimulating new novel, set in the years between Suez and Thatcher, centres on the discovery of North Sea oil, a subject rich in irony, not least because the advent of “black gold”, seen as the bedrock of arguments for Scottish independence, instead shored up the 80s dominance of the Tories – to say nothing of helping to overheat the planet.

The story unspools mostly in the Highlands and involves five main characters, chiefly two pairs of male friends whose contrasting fortunes we follow from boyhood into middle age. Robbie is a farm boy whose luck with the lassies is a torment to Aaron, a shy schoolteacher’s son about to study geology. Then there’s Edinburgh public school pals Mark and Ally, one an aspiring journalist with thoughts of running for office, the other a future financier who ends up holding the keys to every other character’s hopes – including those of Joe, heir to a fishing trawler dynasty on a collision course with the EU as well as a tide of overseas oil prospectors scenting riches.

As the ensemble narrative trots through the decades – Our Friends in the North Sea, you might say – Kelly holds our attention with quick and busy chapters told in the present tense. Date-stamped segments switch from one character to the next with snappy scene-setting sentences, the passage of time neatly generating momentum via, say, an offhand reference to the divorce of characters who only a few pages earlier were married. While the novel’s action hinges on whether Aaron – lured out of academia by an US oil contractor – will figure out the exact spot where his paymasters ought to drill, Kelly’s skill lies in making us care about such questions not only for how they affect the big-picture social upheaval, but for how they tip the seesawing balance of power in Aaron’s cross-class friendship with Robbie, whose livelihood – for good and ill – becomes entwined with burgeoning developments offshore.

Kelly can be excessively brisk and relies too often on lust as a lubricant: pretty much whenever a new female character is introduced, usually with reference to their footwear or hair, you soon guess the part they’ll play. And almost inevitably the book is full of stage-managed conversations about key talking points – the SNP, trade unions, the common market – yet the hokey moments are more than compensated for by the invigorating descriptions of work: gutting fish, welding, drilling (or “making hole”, as Aaron’s bosses call it). Kelly lights convincingly on choice detail: one oil worker prefers life in a deep-sea diving crew to the pent-up aggro of being on the rigs because “the helium in their bodies [makes] their voices comically squeaky, and it’s hard to come on like Jack the Lad when you sound like Donald Duck”.

Because the close-up focus is so compelling, the action so abundant, we seldom question where the novel is heading. Not to give anything away, I’m unsure how far Kelly himself knows; the book more or less abruptly stops, an oil-buoyed Thatcher landslide election victory on the horizon. If you sense rich seams underexplored, there’s also food for thought. Yes, this is a novel of men and masculinity, loyalty, courage, ambition, greed – all of that – but in an age of Extinction Rebellion it can’t help but draw power, too, from the unspoken context when you look up from the page. Where we’re all headed, Kelly seems to say, isn’t only a story for apocalyptic sci-fi; old-fashioned period realism has a thing or two to tell us as well.

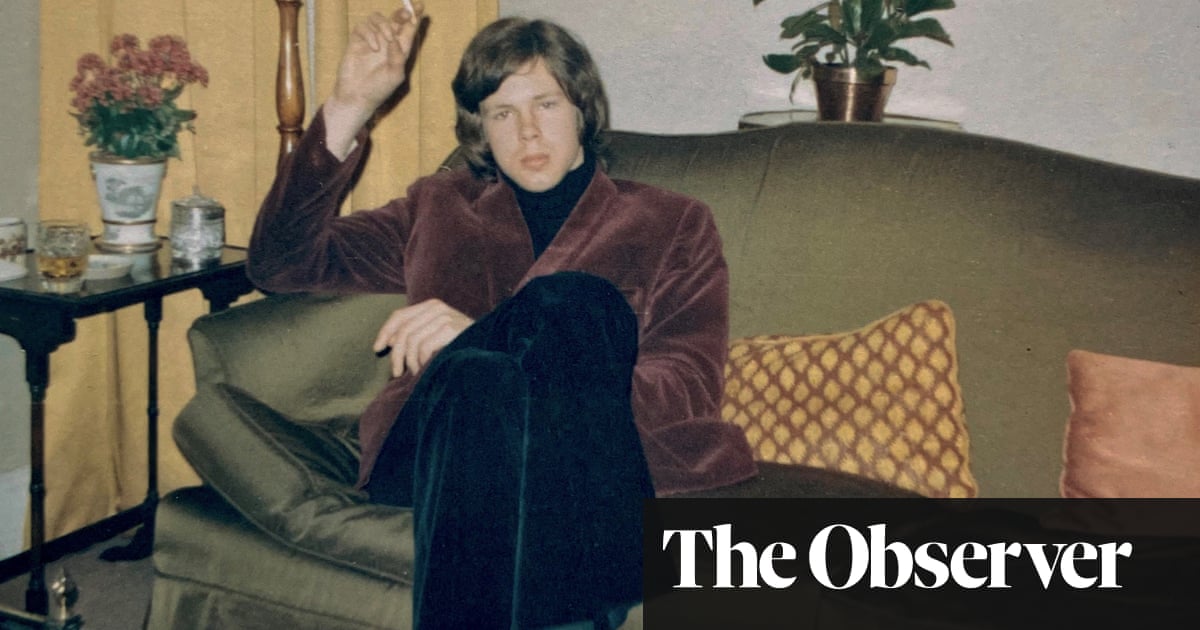

The Black Eden by Richard T Kelly is published by Faber (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply