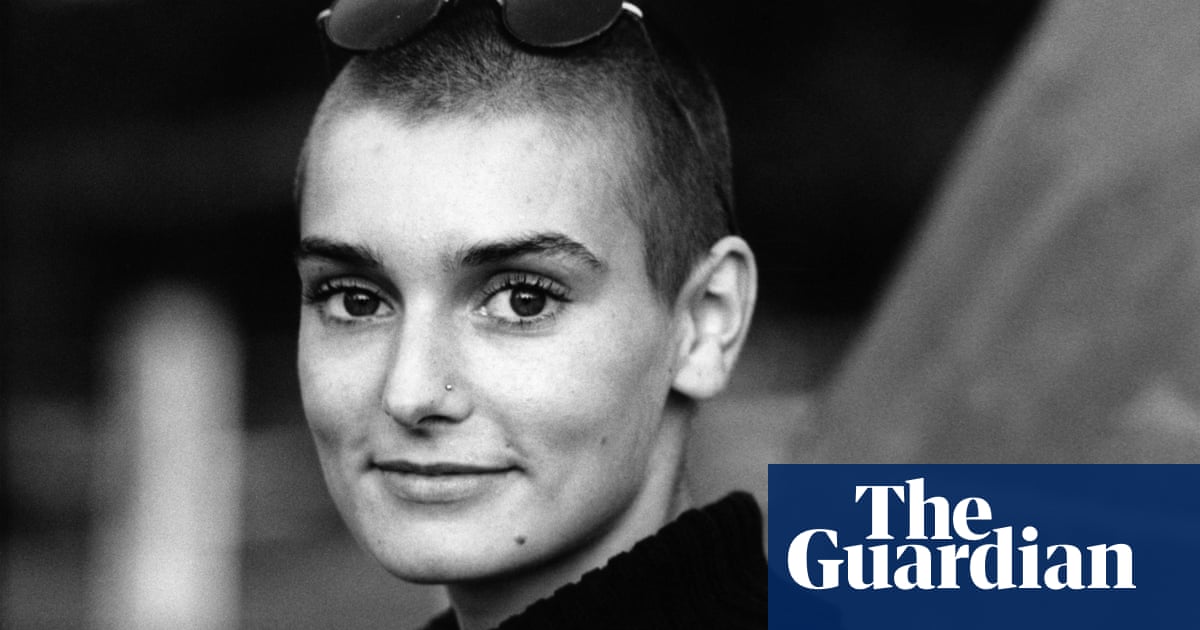

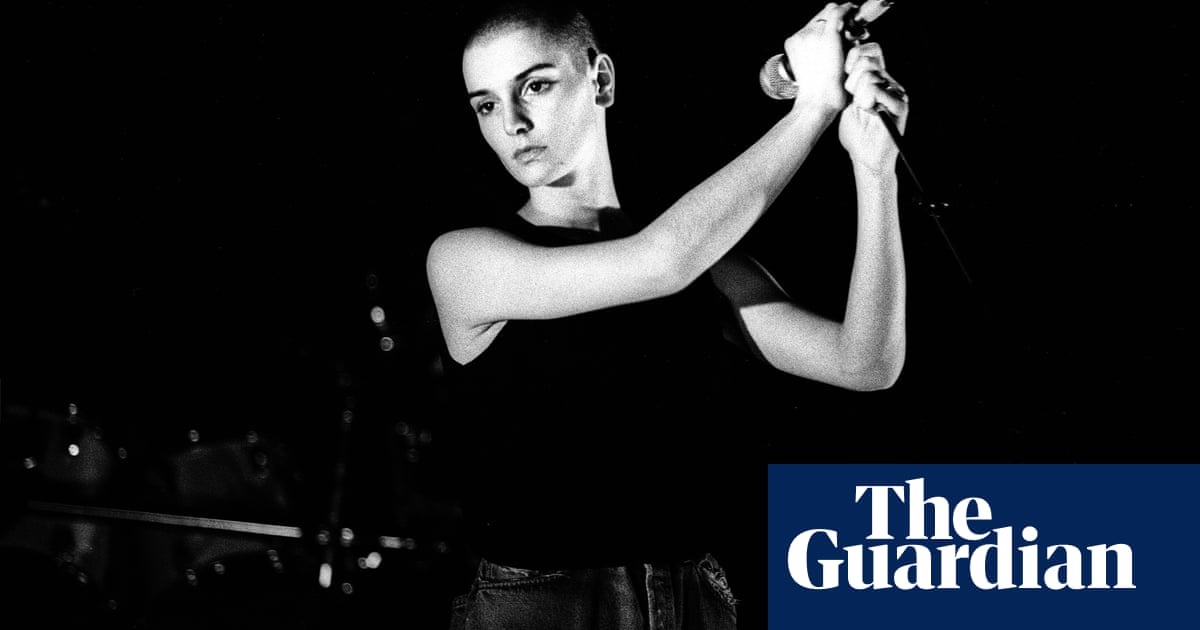

On paper, jungle – one of the defining, pioneering sounds of 90s rave music – and the music of Sinéad O’Connor might not be the most obvious pairing. And yet, in 1995, the renowned Irish artist (later called Shuhada’ Sadaqat) requested UK junglist M-Beat remix her track Fire on Babylon after the pair had met briefly backstage at Top of the Pops the year before. The result was glorious: expansive, shifting beats with her emotive vocal calling out on top.

For M-Beat, real name Marlon Hart, the reason it worked was simple: “Her music had realness to it,” he says. “The common ground that we shared was that our music was very sincere.” At Top of the Pops, he recalls, “I’m an unknown council estate boy who has been lucky to have some songs chart. And I’m meeting this big star. But she was down to earth, she said she really liked our music.”

Beyond dabbling with jungle, O’Connor’s affinity with Black music and, indeed, Black liberation was a through-line in her career. Her autobiography has joyous titbits such as describing Barrington Levy’s vocal genius on Here I Come (“He just cries out, ‘Shuddly-wad-dily-boop-diddly-diddly, w’oh, oh, oh!’ and it says all the millions of thoughts and feelings a man would have in that few seconds better than even Oscar Wilde could have”). As a child she was obsessed with Muhammad Ali, moved by the slavery drama series Roots (which would later inspire the title for her song Mandinka), and fell in love with reggae songs she heard on TV – a love that continued some years later as she visited record stores at Portobello Road market run by Rastafarian elders.

Her late son Shane’s middle names were Ali, after the boxer, and Nesta, Bob Marley’s middle name. She recognised the power of hip-hop and, notably, the reasons the music industry feared it before exploiting it, writing: “A lot of kids of all manner are listening, and no one in the industry wants their top floors threatened by either the wrong skin colour or the wrong mindset – that is, anyone who cares about truth … When showbiz execs realise they can’t kill rap, they will hijack it.”

After her death last month, the internet was awash with stories of O’Connor’s solidarity with Black musicians. The 1989 Grammys debuted a best rap performance category – the mostly white Recording Academy had previously ignored the genre and now insulted it by having the category non-televised. Many artists boycotted the awards show as a result and O’Connor, who was booked to perform, appeared on stage with the Public Enemy crosshairs logo shaved into the side of her head, broadcasting her solidarity. She used a win at the MTV awards the following year to call out the network for not playing rap videos (“censorship in any form is bad, but when it’s racism disguised as censorship, it’s even worse”), showing her support for Florida rappers 2 Live Crew in a time when the courts were trying to ban their album for its purported “obscene” content.

She showed this solidarity and appreciation through her music, too, recording gospel, rap, wobbly dub, James Brown-sampling soul, and roots reggae. Sly Dunbar of prolific reggae production duo Sly and Robbie worked with O’Connor on her 2005 roots reggae album, Throw Down Your Arms, and also describes her as “down to earth. She come to Jamaica, we just cut the album in two weeks. She was a very caring person, very emotional – like she feels what you’re feeling, and she showed it very much. Sometimes she would talk about her faith; she was into [Jamaican activist] Marcus Garvey and finding herself within the whole Rasta thing and really reading the religion. People probably don’t know why she did it – but she knows why she did it.”

Dunbar notes that O’Connor was very much “the one in the driver’s seat” for Throw Down Your Arms. She also worked with R&B producers such as Wyclef Jean and Kevin “She’kspere” Briggs (the latter made the likes of No Scrubs and Bills, Bills, Bills) and in 1994 lent her haunting vocal to Ship Ahoy, a song by radical Irish-British socialist hip-hop group Marxman about the legacy of US slavery. (“It was quite a surprise for the receptionist to see one of the most famous singers on the planet rock up and ask for some random band making demos,” they told the Irish Examiner earlier this year.”)

O’Connor also contacted MC Lyte about a collaboration on the remix of her 1988 track I Want Your (Hands on Me). In a Guardian article commemorating O’Connor after her death, Lyte noted: “I think she appreciated the genre for its honesty, and for the ability of those in it to speak a language that was not accepted by the mainstream.”

That desire for truth, and her experiences of marginalisation and disfranchisement as an Irish woman in the music industry (not least one who was a mother and who had dealt with child abuse in her own youth) feel central to understanding O’Connor and what drew her to these voices. As journalist and professor Jason King recently wrote in his appraisal of O’Connor’s life as a “freedom singer” for NPR that she “saw parallels between the historical suffering and transatlantic dispossession of Black people and Irish people and she reflexively deployed her music in an attempt to lay down cultural bridges”.

This awareness of connected sorrows is something that Boston-based singer-songwriter Shea Rose notes in O’Connor, too. “From understanding her life story, she’s a person that embodied a lot of suffering,” Rose says. “And because of that she could recognise and understand universal suffering in all areas of the world.”

In 2016, Rose covered O’Connor’s 1990 track, Black Boys on Mopeds. The harrowing song was originally released as a response to the deaths of two young Black men: Nicholas Bramble, who was killed while being pursued by the police when it was mistakenly assumed he had stolen the moped he was driving, and Colin Roach, who died in suspicious circumstances in the entrance of a London police station. More than two decades later, after the deaths of Michael Brown, Alton Sterling and Philando Castile at the hands of the police in the US, the song remained horribly relevant and so Rose decided to release her version.

It spoke to her, she says, because of how O’Connor drew from her own experiences to paint a bigger picture of what was going on in the world. “She gives these beautiful vignettes, these snapshots of different scenes of people who are marginalised, dealing with oppression, not being treated like human beings. And then the pinnacle in the chorus” – the lines ‘England’s not the mythical land of Madame George and roses / It’s the home of police who kill blacks boys on mopeds’ – “is the climax of what happens when we don’t treat each other with civility.”

Of course, as Seun Kuti, Nigerian musician and son of Fela Kuti, points out, O’Connor’s politics were not limited to Black liberation. Seun appeared on her final album, 2014’s I’m Not Bossy, I’m the Boss, and stresses: “What we should really celebrate is not her standing up for artists or engagement with music from African people or Black people, but the fact that she stood for truth. That’s the biggest weapon in the artillery that people have to fight oppression. She was able to stand for the people by speaking truth to power, always. And in that aspect, I think she showed more respect for African people, African art, than any other thing that she could have done. And not just African peoples; I mean, she converted to Islam, this woman was speaking on behalf of Palestinian people, on behalf of Indian women. She lived a righteous life. And in a capitalist imperialist system like this, being righteous is crazy.”

Seun compares how the mainstream media mocked O’Connor with the way his father was discredited for his revolutionary views. But as with Kuti, he sees the potential for her message to resonate long after her untimely death. “Her mission in life was for the world to be a better place for everybody,” he says. “I don’t think it’s too late for that.”