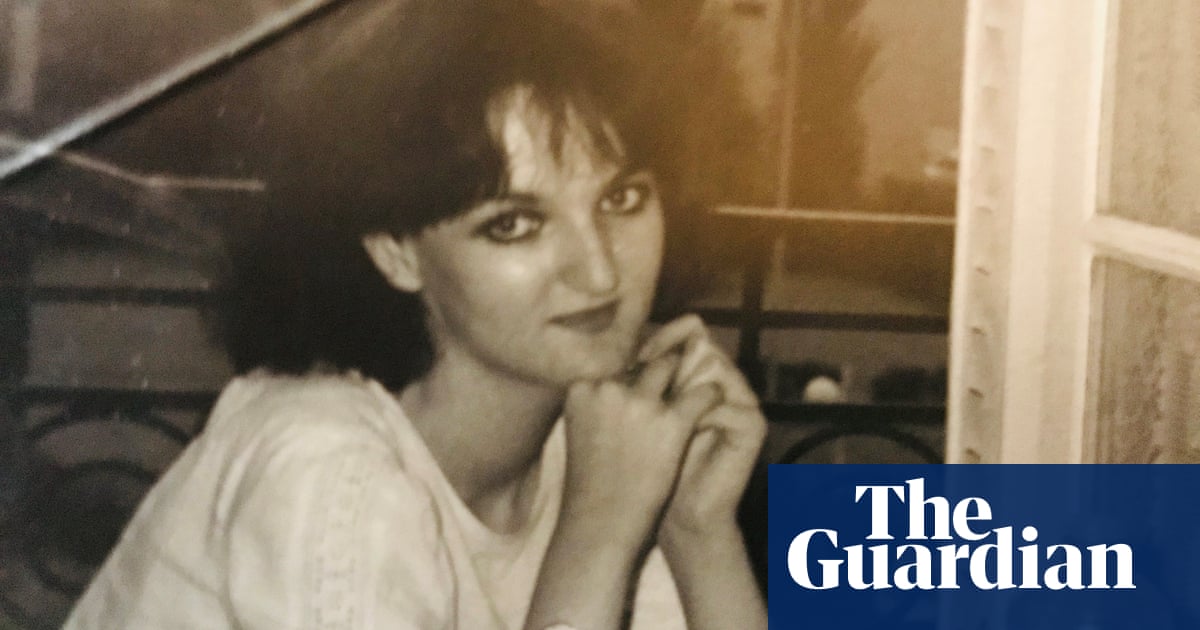

The Secret of Cooking sprang from personal experience. I wanted to crack the code of how to fit cooking into the everyday mess and imperfection of all our lives without it seeming like yet another un-doable thing on the to-do list or yet another reason to berate ourselves for falling short. My own relationship with cooking changed, suddenly, about a year into this project. In June 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, my husband of 23 years, the father of my three children, left me for another woman. For much of that year, I resembled Munch’s painting The Scream (or at least, that is how I felt). I tried anything I could think of to take my mind off the grief – watching box sets, yoga, reading novels, vodka – but almost everything reminded me of him, especially the vodka. With social distancing in place, I couldn’t hug friends. My mother, who had dementia, was in a care home where I wasn’t allowed to visit. To cap it all, I suddenly had to do all the laundry and all the cooking. This wasn’t such a shift; we never divided the cooking 50/50. But there is still a difference between being the person who does the majority of the cooking and being the person in charge of all of it.

To my surprise, I found that my enforced new role came with benefits. In my lonely state, the kitchen was one of the few places I felt better rather than worse. Cooking anchored me to the person I had been before I met my husband. I could make myself a chicken stew with the sweet scent of parsley and white wine which reminded me of the stews my mother used to make. No matter how tearful I had been the night before, I still had to get up in the morning and cook breakfast for my son, who was then 11. The act of cracking eggs into a jug to make his favourite pancakes or waffles felt steadying and gave me back my appetite.

We spend so long in the modern world talking about the stress of cooking that we can miss the ways in which cooking itself can be the greatest of all remedies for stress. Cooking brought me out of my thought loops and back into my senses and into a world of good smells and sounds. If I could pay enough attention to the sizzle of garlic in a pan or the squeaky sound of mushrooms frying, I could forget darker thoughts.

I also felt good about the fact that I was keeping myself and the children nourished. We seemed to connect more deeply over meals than we had before. My teenage daughter and I have always shared a love of eggs, but in the past we tended to eat them for lunch in limited ways (boiled, scrambled, shakshuka). Together, we branched out, taking it in turns to cook them and discovering new methods for making an omelette especially tender and delicious. (When you are making a basic omelette and want an instant fix to improve the texture, add a dab of dijon mustard. Dijon is both an acid and an emulsifier and these two things together do transformative things.)

I am not pretending that cooking mended my broken heart. When life sucks, it doesn’t stop sucking just because you have cooked the best pavlova of your life or figured out how to make a vinaigrette that works every time. But these things also don’t hurt. My rekindled love of cooking made me more determined to find ways to make it much easier, both for myself and others. Almost all of us have at least one cooking secret up our sleeve, shortcuts or flourishes we get so used to doing that we forget how special or unusual they are. I bought a large green notebook with a soft cover and started collecting kitchen tips from friends and books.

I learned so many shortcuts that I wish I had known years ago. I found that, contrary to what almost every recipe says, it is not essential to sauté the vegetables for a soup or stew or sauce – you can just simmer it all together in the pan, which makes the whole process so much less effort on days when you are exhausted. Another discovery was that I could make the most delicious, buttery tomato pasta sauce in almost no time at all using a box grater. I started to reprogramme many of my assumptions about how to get food on the table (or into a lunchbox, as the case may be). One of the most mind-blowing discoveries of all was that it is often not necessary to preheat the oven, even when making a cake or roasting a chicken. Oh, and you really don’t have to start every recipe with an onion (unless you want to).

Making cooking more enjoyable is largely a question of timing. We are often told we don’t have time to cook, but the part we miss is that time is not a single thing. Time is not just about how much or how little we have; it’s about the quality of those minutes and when in the day they fall. The real secret is we need the cooking that suits the particular time we have. Sometimes you have acres of headspace to plan a meal but little time for cooking and sometimes it is the other way round. I found one way to save huge amounts of time during the week without any compromise on taste was to make universal cooking sauces in advance and store them in my freezer, so I could have the makings of a delicious red or green or yellow curry at short notice without ordering delivery food.

The secret we all need the most is how to get the spark of cooking back into our lives so that the kitchen becomes a place we actually want to be. Delicious is not just about the way food tastes; it is a mindset. More than anything, the secret ingredient that makes the difference in the kitchen is enjoyment. And what this means is that we have to learn ways to make food that delights us, because no cook enjoys making a dish when the end results are disappointing. One of the secrets I discovered was that cooking can be a series of remedies which made me feel strangely calmer and more equipped to deal with the rest of what life had to throw at me.

Ruth’s tuna salad with anchovy dressing (pictured above)

If you like mayonnaise-type dressings, this is salad as pure comfort food. My mother-in-law, Ruth, is the only person I know who always refers to tuna as tunny fish. Someone else might call this a kind of salade niçoise, but to Ruth it is always tunny fish salad. I have lost count of the number of times I’ve eaten this at her table. Everyone who eats it falls in love with the dressing, which is based on one in Keep It Simple by Alastair Little, although Ruth changed it quite a bit. It sounds unlikely: a kind of mayonnaise-like concoction including tomato ketchup and anchovies. But somehow, it works. The dressing mixes deliciously with the tuna, and it is as if the green beans, tomatoes and eggs are dressed with anchovy-infused tuna mayonnaise.

This makes enough dressing for two salads for three people. What I usually do is serve it the first night as written, and then to ring the changes, the second night we have it without the potatoes in the salad but with baked potatoes on the side.

Serves 3 (with leftover dressing)

For the dressing

egg 1 whole

anchovies 1 small tin (the ones I buy weigh 55g)

garlic 1 clove, peeled

lemon juice of 1

ketchup 2 tbsp (or tomato purée)

neutral oil 200ml (or a mix of half and half light and extra virgin olive oil)

For the salad

small new potatoes 300g, cut in half or quarters, depending on size

green beans 200g, topped and tailed

cherry tomatoes 200g, washed and halved

radishes 100g, washed and sliced as thinly as you can (this is my innovation; please don’t tell Ruth)

eggs 4

tuna 1-2 tins

lemon wedges to serve

First, make the dressing. Put everything except for the oil into a large measuring jug and thoroughly blitz with a hand-held blender. Now slowly drizzle in the oil, continuing to blitz until you have a thick mayonnaise-like dressing. Taste a bit on a piece of bread or raw vegetable. It should be ambrosial. I don’t usually add salt because anchovies are so salty. Adjust for lemon and ketchup.

Now for the salad. You need two medium-sized saucepans. Boil the kettle. Put the potatoes into one of the saucepans, add boiling water and a teaspoon of salt and boil for 10-15 minutes, or until tender. Drain in a sieve or a colander. Meanwhile, boil the kettle again. In the second pan, boil the green beans with a pinch of salt. They may take 4 minutes or they may take 8. It hugely depends on how fine they are. You want them properly tender, not squeaky (or at least, that’s how I like them). When they are done, remove them from the pan with a spider strainer or slotted spoon and put them into a big salad bowl. Add the eggs to the pan and boil for 8-9 minutes until hard boiled but still with a tiny bit of squidge in the yolk. Plunge into cold water and peel.

Drain away any water that has accumulated in the salad bowl with the green beans. Add all the other ingredients except the eggs and toss with a little under half the dressing. Halve the eggs, arrange them on top and serve with extra dressing on the side plus wedges of lemon, lots of black pepper and perhaps some bread to mop up the dressing.

Ratatouille for Richard

My friend Claire Edwards is French and has a thing for ratatouille. As a joke, she adds a syllable and calls it ra-ta-ta-touille. When our children were little, we went on holiday together a few times and the thing I remember most is being in the kitchen with Claire for hours, roasting a big chicken and making her ra-ta-tatouille, a slow process which left lots of time to talk as we chopped the courgettes and peppers. She would make great vats of it, enough to last for several meals. I can remember the wide smile of appreciation on her husband Richard’s face when she finally put it on the table. In early 2021, Richard died suddenly of a stroke aged 54, a loss which can hardly be borne.

Technically, the ratatouille I now make is not ratatouille at all. It is – as requested by my youngest son – based on the one eaten by the food critic Anton Ego in the Pixar movie Ratatouille. Properly, it should be called a tian, because unlike classic ratatouille, it is not stewed in a pan but constructed from very thinly sliced vegetables, baked in the oven. It looks much fancier this way but the flavours are the same: the gentle fragrance of sweet garlic mingling with oil and aubergine and tomato. You can get it ready ahead of time and reheat, if it helps.

It makes a spectacular vegan feast, perhaps with a simple pilaf of rice cooked with bay leaves, onions, oil, stock and herbs; or with baked potatoes and guacamole. But my default is still the way Claire served it, with a roast chicken, some roast, boiled or dauphinoise potatoes and a green salad.

Serves 4-6, depending on what else you are having with it (it’s a good idea to double it and make two)

extra virgin olive oil 100ml

garlic 6 cloves, peeled and grated

plum tomatoes 1 × 400g tin

sugar a pinch

courgettes 3 large (about 450g)

aubergines 2 large

vine tomatoes 6 large

thyme a few sprigs, leaves stripped and chopped

Preheat the oven to 190C fan/gas mark 6½. In a medium saucepan, heat 20ml of the olive oil over a medium heat and sauté 2 of the grated garlic cloves for a few seconds before adding the tinned tomatoes and a big pinch of salt plus a smaller pinch of sugar. Cook, stirring often, until it reduces down a bit. Now, either mash it a bit with your wooden spoon or blitz it with a hand-held blender. Spread this sauce over the bottom of a large casserole dish or wide-lidded ovenproof pan.

Cut the courgettes paper-thin using either a mandoline or a food processor. Now cut the aubergines in half lengthways and cut them too, using a mandoline or a food processor. Finally, slice the tomatoes as thin as you can using a sharp knife and a chopping board (I find they get mashed by the processor). Make stacks of the aubergine, courgette and tomato and arrange these in circles in the dish. When I first made this, I was completely obsessive and felt I had to alternate the vegetables one by one. This was time-consuming and it also didn’t work, because I always ended up with lots of aubergine and courgette left over (there are fewer tomato slices than aubergine and courgette). So what I now do is take a little stack of aubergine, a stack of courgette and then a single tomato slice and go round like that. It looks just as good.

When the pan is full, sprinkle over the thyme and distribute the remaining garlic as evenly as you can, tucking it into the crevices. Sprinkle the whole thing well with flaky sea salt and pour over the remaining olive oil. Put it into the oven for 30 minutes, then put the lid on and return it to the oven for another 30 minutes, or until the vegetables are completely tender and a little bit shrunken.

Restorative white bean stew

It was the brilliant chefs at Vanderlyle restaurant in Cambridge (Alex Rushmer and Lawrence Butler) who taught me that the broth in which white beans cook can be as soothing as chicken stock. In the past, I would foolishly rinse the beans after cooking them, thus throwing the best bit away. When you are tired, cooking dried beans can feel like too much effort, but you don’t have to soak them. These can happily simmer away in the background. The hands-on cooking here is minimal and the results are pure comfort.

Serves 4-6 or more, depending on how many of you are children

dried white beans 250g, such as cannellini

flat-leaf parsley 30g, chopped (or any other herb of your choosing)

garlic 6 cloves

new potatoes 600g

courgettes 2 medium, or 2 large carrots

spring onions 100g

white wine or vermouth 150ml

lemon zest and juice of 1

double cream (or coconut cream to keep it dairy-free)

Put the beans into a medium-large saucepan, add half the parsley and the whole cloves of garlic, cover with masses of water and bring to simmering point. Simmer for around 2 hours, or until the beans are totally tender. This is the unpredictable part, but it really isn’t strenuous. Dried beans can cook in anywhere from 1½-3 hours without soaking. Just check them every half an hour and keep topping up with water as needed.

When they are tender, chop the potatoes, courgettes (or peeled carrots) and spring onions into small pieces and add them to the pan along with 1 teaspoon of salt (leave it out if cooking for toddlers and season at the table for non-toddlers) and the wine. Put a lid on the pan and simmer for a further 15 minutes or until the potatoes are tender. Adjust the seasoning with lemon and add a big slosh of double cream and the second half of the parsley.

Roasting-tin chicken with fennel and citrus

This, adapted from Bitter Honey by Letitia Clark (a cookbook of Sardinian food which helped keep me sane during the first lockdown), is one of my most made roasting-tin meals. I find it comforting and uplifting at the same time.

Crispy skin on chicken thighs cook in a tray with fennel (both seeds and vegetable), white wine, citrus and dijon mustard. The fennel becomes impregnated with the wine and the chicken fat until it is meaty and sweet and sour.

If you decide to scale this up when cooking for more people – which is a great idea – don’t scale up the liquid too much or the chicken will drown in it. If you triple the amount of chicken, only double the liquid.

Makes 2 portions

unwaxed lemon zest and juice of 1

unwaxed orange zest and juice of 1

dijon mustard 2 tsp

extra virgin olive oil 2 tbsp

fennel seeds 1 tsp

white wine 200ml

chicken thighs 4, bone in, skin on

fennel bulbs 3, fronds reserved, bulbs cut into wedges

fat green olives a handful

If you are feeling organised, start the day before or a few hours ahead. Whisk together the citrus juice and zest, dijon mustard, olive oil, fennel seeds, wine and 1 teaspoon of sea salt, and put into a freezer bag along with the chicken. Chill for a couple of hours or up to 12 hours. This will help to tenderise the chicken. But in all honesty, I’ve often forgotten to do this and it still tastes great.

Either way, put the chicken and all the marinade ingredients into a roasting tin. Slice the fennel bulbs into wedges and add them, along with the olives. Put into the oven and switch it on to 200C fan/gas mark 7 for an hour, or until the fennel is meltingly soft and the chicken is bronzed (check after 45 minutes).

Taste the sauce for seasoning. If the wine has all evaporated away, splash some water into the pan to make a simple gravy. Taste again for seasoning. It shouldn’t need much, because of all that citrus and wine. Eat with some crunchy green fennel fronds on top and good bread for mopping.

Raspberry ripple hazelnut meringue

This gluten-free meringue is spectacular and very easy – a pavlova flavoured with toasted hazelnuts and filled with cream rippled with raspberries. I got the idea from Jeremy Lee, the chef-proprietor of Quo Vadis restaurant, who makes a similar meringue but with almonds. The addition of the nuts makes it twice as nice, in my view, but obviously if you are serving the meal to anyone who can’t eat nuts, you can just leave them out and it’s still a thing of splendour. The meringue itself can be made ahead of time (even 1-2 days ahead), and then all you have to do is whip the cream and assemble it with the fruit.

Serves 8

blanched hazelnuts 120g

egg whites 5 (save the yolks to make pasta or custard)

cream of tartar ¼ tsp (optional, but helps the egg white to hold its shape)

caster or granulated sugar 275g

raspberries 400g, washed

icing sugar

double cream 400ml

Line a large baking tray with baking parchment. Heat the oven to 170C fan/gas mark 5. Scatter the hazelnuts on the tray and roast until their colour is just starting to deepen and they smell wonderful (about 10 minutes). Tip them into a food processor and grind very coarsely (there should still be some big pieces). If you don’t have a food processor, chop them by hand.

Using an electric whisk, beat the egg whites with the cream of tartar in a large, clean mixing bowl until they are stiff and very white. Slowly add the sugar and continue to beat until glossy. Fold in most of the ground nuts, keeping back a large handful, using a large spatula or metal spoon.

Tip the meringue on to the lined tray and spread it out to make a rough circle shape of about 24cm. Scatter the remaining hazelnuts on top. Bake the meringue for 20 minutes, then reduce the oven temperature to 120C fan/gas mark ½ and bake for another 40 minutes. It should look a divine pale biscuity-brown: the colour of a fawn whippet. Leave it to cool out of the oven.

While the meringue is baking, take 125g of the raspberries and press them through a sieve to make a purée. Mix this with 3 tablespoons of icing sugar to sweeten. Whip the cream with 1 tablespoon of icing sugar until it reaches soft peaks. Swirl half the raspberry purée into the cream to make a ripple. Dollop it over the meringue, followed by the rest of the whole raspberries. Drizzle the remaining sweet raspberry purée over the top and dust with icing sugar. At this point, according to Jeremy Lee, the cook should “take a bow”.