They sent an army helicopter to take me to Woodstock, or at least an army-style helicopter. As I flew in I couldn’t see the whole crowd, but you could see enough people dotting the landscape that it was hard to believe that there were even more. “Goddamn”. I said to myself. “Goddamn. What the fuck is this?” So many people, an ocean of them without any land for miles. When something is that big a deal, be sure you’re ready.

That was still my thought on stage. Did I feel the moment as pressure? I knew we had to live up to it, not to mention rise to the level of the other artists. Janis Joplin was on before us, and then there was a break, and it was like the sky split open with rain. More than one of us was afraid to touch the equipment because of the danger of getting shocked.

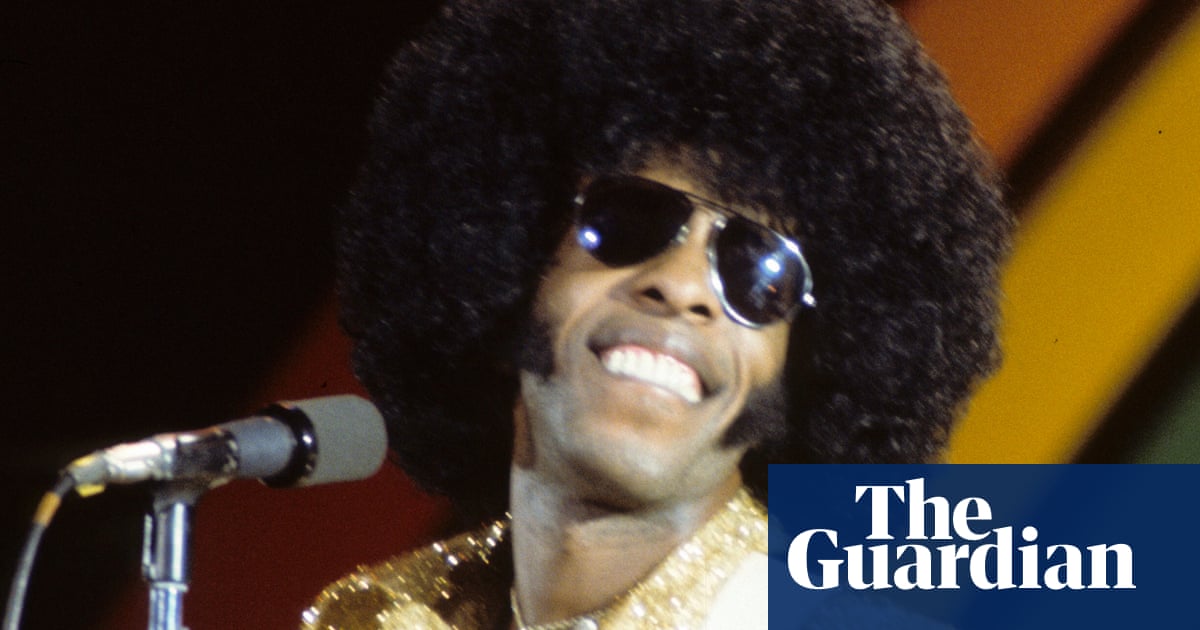

We went on around 3:30 in the morning and opened with M’Lady, with its big vocal breakdown at the end and the band storming back in to finish it while the weather did the same all around us. We rolled into the guitar-and-organ intro to Sing a Simple Song, and rolled through You Can Make It If You Try. We were leaving a record behind in the air, in the minds of the people who were there. Next we played Everyday People. We were building to I Want to Take You Higher. By now it was past four in the morning, still dark, but I could see more of the crowd in the predawn light. Goddamn.

I was thinking what would happen if I said something and they all said it back. What would that sound like? So I tried it. I took the microphone and spoke to everyone.

“What we would like to do is sing a song together. And you see what usually happens is you got a group of people that might sing and for some reasons that are not unknown any more, they won’t do it. Most of us need to get approval from our neighbours before we can actually let it all hang down. But what is happening here is we’re going to try to do a singalong. Now a lot of people don’t like to do it. Because they feel that it might be old-fashioned. But you must dig that it is not a fashion in the first place. It is a feeling. And if it was good in the past, it’s still good.”

I sang, “I want to take you higher”, and they sang back the last word, “higher”. All of them. Damn. We kept it going. I kept it going.

“Just say ‘higher’ and throw the peace sign up. It’ll do you no harm. Still again, some people feel that they shouldn’t because there are situations where you need approval to get in on something that could do you some good.”

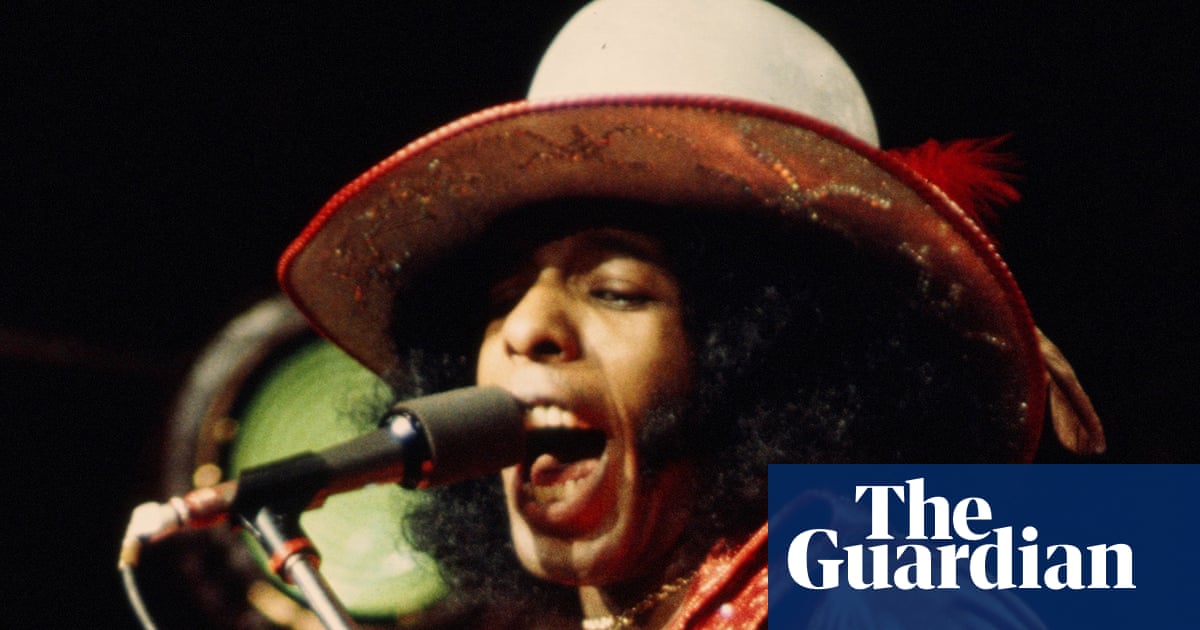

Higher went out. Higher came back. What the word meant widened. It wasn’t just keeping yourself up with a good mood or good drugs. It was defeating anything that could bring you down.

“If you throw the peace sign up and say ‘higher’, you get everybody to do it. There’s a whole lot of people here and a whole lot of people that might not want to do it, because if they can somehow get around it, they feel there are enough people to make up for it. We’re going to try ‘higher’ again, and if we can get everybody to join in, we’d appreciate it. It’ll do you no harm.”

A wave crashing on to the shore of the stage. Way up on the hill …

“Want to take you higher!” / “Higher!”

“Want to take you higher!” / “Higher!”

“Want to take you higher!” / “Higher!”

The call, the response. It felt like church. By then the film crew was fully in place. The horns went up into the sky. When the show was over, we were wet and cold. I don’t remember how I left, maybe the same way I came in, but I wasn’t there to see Jimi close the festival.

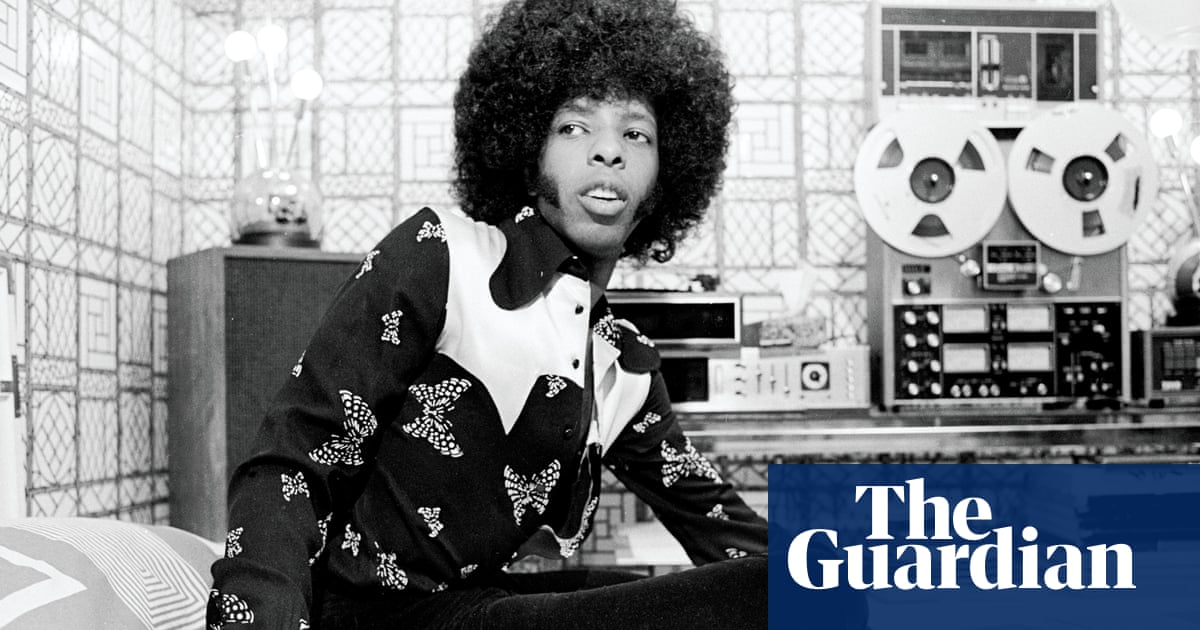

By the next day it was clear that Woodstock had been a big deal, and that we had been a major part of that deal. The festival had put a spotlight on lots of groups, but us and Jimi the most. What really made it clear to me was when my manager David Kapralik gave me a Stellavox tape recorder, one of the best in the world. This is a nice motherfucker, I thought. Why would you give that to me? And then I answered myself: Because I kicked ass.

“Sly! Sly! Sly!” I turned around at the third one. I was in New York for a party at someone’s apartment, and George Clinton was there too. I hadn’t seen George for a little while. Since we had toured, Parliament had put out some bigger albums, and then Funkadelic had, and George had started a thousand offshoot bands, too. But he was starting to burn out from juggling it all: acts, labels, tours, money, drugs.

We talked for a long time at that party. He told me that he was heading up to his farm in Michigan, and that I could visit anytime. “Maybe I will,” I said. I did. Country living was clean air and a lack of distraction. We went fishing, made music, and got high, not always in that order.

George was a trip. I always thought of him as a human cartoon. If there was a way to make an experience more fun, he would find it. He was funny on his own, and together we were even funnier. If I wanted money to score I didn’t have to lie and say that I was buying equipment or giving a girlfriend money for clothes. I would just come right out and ask: “Can I star?” But in this case, the headliner got attention first.

Even though George and I used together, we didn’t use in similar ways. He would go to sleep earlier and I would stay up later. He would stop and I was just getting started. Sometimes after he was in bed, I needed more drugs. I would write dope notes and slide them under his door. There was one he liked to bring up: “Knock knock. Put a rock in a sock and send it over to me, doc. Signed, a co-junkie for the funk.” By now the drugs were in rock form, made with baking soda and called crack because of the crackling noise it made when it was heated up.

We met a dealer who knew every song from every Family Stone record. We had to wait for the drugs while he asked detailed questions. Was it a harmonium on that song? What was the gear we used for the other one? One afternoon on the way over there George and I realised that we didn’t have money for dope. When we got there I didn’t wait for the dealer to start talking about my music. I went in on it myself.

And then I hit him with a bonus. “We’re light,” I said, “but I’ll give you a copy of the album I’m working on as collateral. You can’t listen to it, but you can keep it safe for me.” I went out to the car and came back with a tape. I think his hand was shaking when he gave us the drugs, he was so excited.

On our way home, George congratulated me on thinking fast. “Good idea to give him a copy of the record.”

“What record?” I said.

He was staring at me like I forgot something that had just happened.

“You know,” he said. “The tape. The music.”

“There’s no music on there,” I said. “There’s nothing. It’s empty.”

I don’t know how long George laughed, but it seemed like it was the whole ride home. He eventually told the dealer, who wasn’t even mad. “You have to respect that,” the dealer said.

I decided to get clean on the fourth visit to hospital in 2019. The first time, I was feeling bad at home, faint and weak, having trouble breathing, so I called Arlene, who was my girlfriend back in the 80s and is now my friend and manager. I called her and she called the ambulance. I was in and out of the hospital before anyone could get comfortable with the idea of me being there. I only wanted to get home and keep doing what I was doing, which included drugs.

The second time, the doctor said, “If you go home and smoke again, you could die.” I heard him but I didn’t believe him. I went home and smoked again.

The third time was a terrible scene. I was exhausted that time and weakened, and the hospital wanted to keep me longer so I could get some rest and some tests. I wanted out. I wanted home.

Arlene may not have agreed, but she understood that I had made up my mind. To be let go I had to sign a release saying that I took full responsibility. When they let me go, I didn’t even get a wheelchair. I got on my feet, barely. I got into the hall, barely. I started to walk, barely. That corridor went on farther than I could imagine. It took more than an hour to make it from the room to the car.

The fourth time came just two weeks later. That time, I not only listened to the doctor but believed him. I realised that I needed to clean up. I concentrated on getting strong so that I could get clean. My kids visited me at the hospital. My grandkids visited me. I left with purpose.

I went home. Arlene cleared the house of things (lighters, pipes), of people (dealers, users). There was even an Uber driver who had been staying with me, and he got put out too. Arlene hired caretakers instead and made sure that either she or my daughter Phunne stuck close to oversee the situation, make sure drugs didn’t creep back into the picture. If it had been visit one, two, or three, who knows what would have happened? But it was visit four and I knew what needed to happen. People say that when you kick, you take it one day at a time. I didn’t. I just decided that I would quit and I did. It wasn’t that I didn’t like the drugs. I liked them. If it hadn’t been a choice between them and life, I might still be doing them. But it was and I’m not.

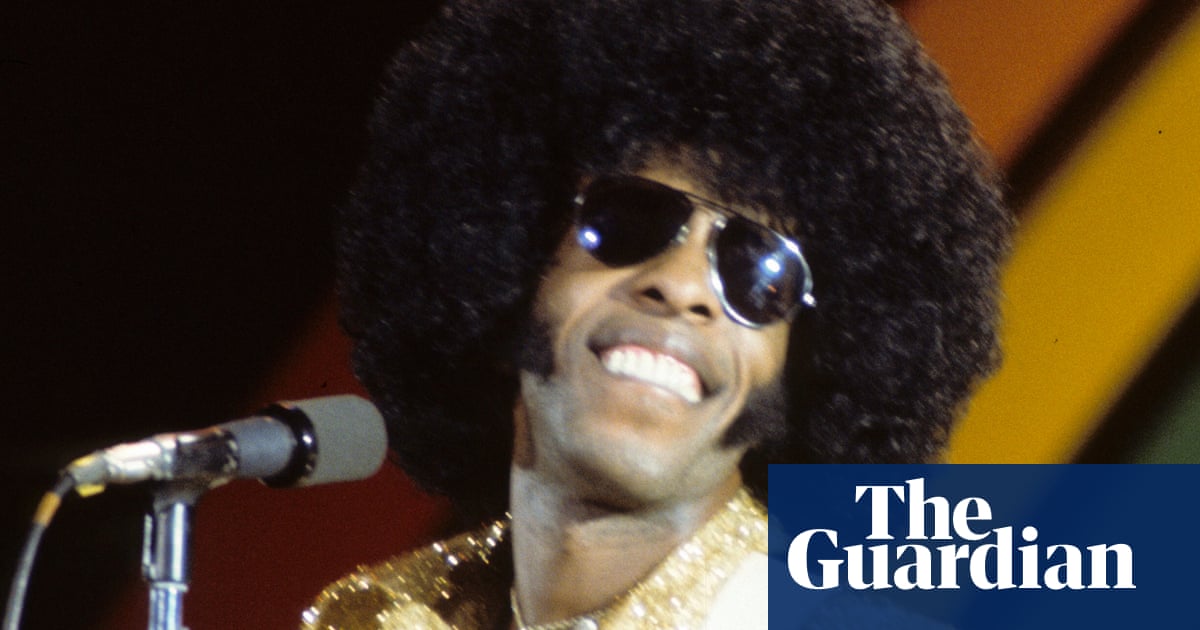

Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin) by Sly Stone is published on 17 October by White Rabbit (£25). To support the Guardian and the Observer buy a copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply.