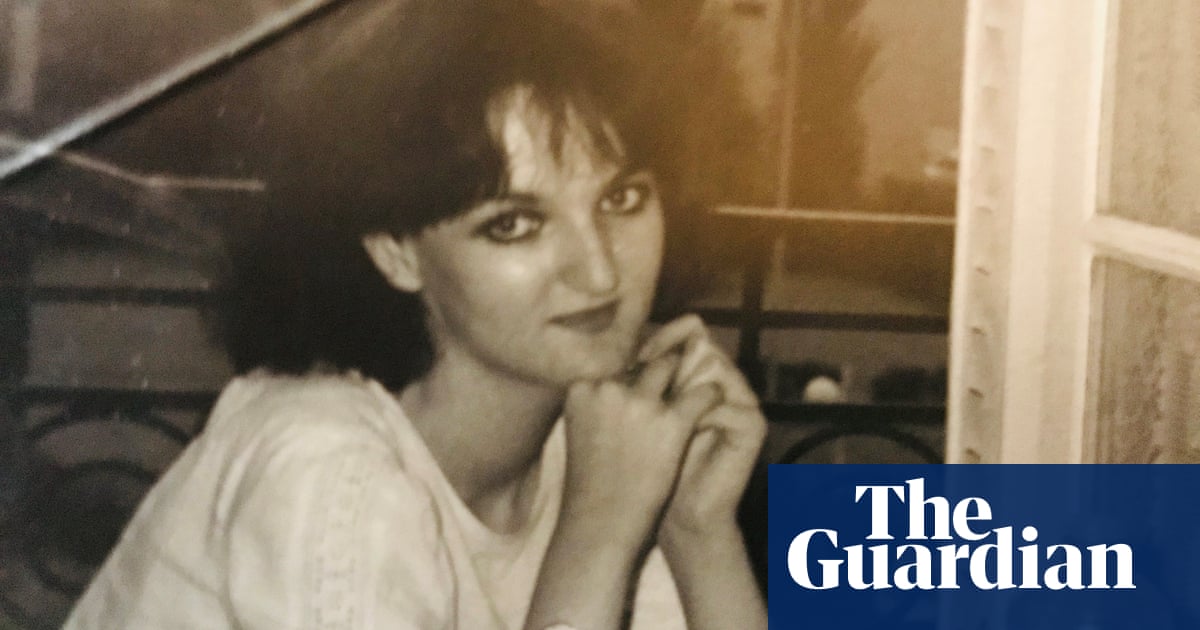

When my mother lost most of her sight just before Christmas 2022 it was a bolt from the blue. She has always seemed quietly invincible to me. Despite the many devastations life has thrown at her, she is a fiercely independent spirit who keeps her head down and gets on with things. She has survived breast cancer, losing several of her siblings and many other tribulations.

Through it all, every December without fail, she ensures that we have a great Christmas. She has always believed in the magic of the festive season. It isn’t just for children, in her view, but for the adults who have endured so much over the course of a year. They deserve a feast, the sense of communion that comes with it, and the human connection that feels so potent at this time. As it can also be a terribly lonely period for some, my mother has always invited relatives who have no one to spend that time with.

Along with her sight loss last year, she was diagnosed with Charles Bonnet syndrome, a condition where sufferers experience visual hallucinations that can be either fairly innocuous or terrifying. In her case, they were dark, incessant and crippling, affecting her mental health and her sense of self.

Consultants at the hospital told us matter-of-factly that there was no chance of her sight improving. The likelihood of a good Christmas felt inconceivable – we were all traumatised. Suddenly, the festive fanfare around us became a sore point. I had always enjoyed seeing the decorations and feeling the excitement building but, after my mother’s diagnosis, Christmas changed for me. I chewed over this grim new reality.

In early December last year, I felt a great anger rising as I watched my mother struggle to do simple things. She couldn’t read books any more, which distressed her. I organised audiobooks to be sent to her from the Royal National Institute of Blind People library, but CDs of books she’d normally be keen to read sat languishing on her shelf.

Her sense of equilibrium was affected on trips to the local store. She needed help checking her emails, paying bills, doing errands she’d always handled efficiently. I was raised as a Christian but how could God allow this to happen? Suddenly she was ageing before my eyes. Always a discreet woman, she tried to keep her pain private, but her sight loss brought everything to the fore.

Two weeks before Christmas she called me to say: “Let’s go shopping.” It was her favourite solution to a personal tragedy. We bought enough food to feed a small village. As is the custom in our family, we spent Christmas week together. On Christmas morning, my sister and I were her eyes. We all cooked together, making jollof rice, salad, roast turkey, pepper soup, moi moi and grilled vegetables. We laughed and shared stories. My brother blasted his Christmas music playlist, which got us dancing between tasks. At lunch, we spoke about our hopes for the coming year.

My mother couldn’t see our faces at close range. Instead, our heads looked like wasps or amalgamations of other strange things. I cannot imagine the pain this caused her. Despite this, she maintained her sense of humour and mischief. She beat me at several games, including charades – her competitive streak was still in full force. We stayed up late talking.

I know now that I’ll never take the joy of Christmas for granted again because things can change so quickly. Last year taught me that, ultimately, I’m still an optimist, even when going through tough periods, and every Christmas spent with my mother and siblings solidifies our bond in subtle ways that I can’t begin to express.

My mother did something miraculous last Christmas. She saved my love for it when it was dwindling away. Through a mysterious process of motherly osmosis, I have inherited her determination to ensure that it’s still a special occasion. I will always be eternally grateful to her for such an incredible act of love. She remains a constant inspiration to me.