The sense of an ending is what this fascinating film delivers: an unimaginably painful ending and the moral reckoning that has to follow. This dreamlike satire from Georgian film-maker Tengiz Abuladze, was made in 1984 but suppressed for three years before release. This was not so much for its coded critique of Stalinism – of which the Soviet authorities had long since learned to parrot their regretful disapproval – but of the pusillanimous loyalty to the Stalinist memory that persisted in the USSR for generations, and the taboo that even then forbade serious reassessment of Stalinist crimes and exhumation of its buried horror. Now Repentance is revived and its strange theatricality and madness are more disturbing than ever.

Partly a bizarre parable, it is an absurdist social-surrealist attack on power and state violence. Like Blue Mountains, made at about the same time by Abuladze’s fellow Georgian Eldar Shengelaia, it is an eerie premonition of the Soviet empire’s complete collapse, just years away. But the tone of icy ironic detachment is swept away in the film’s closing section by a howl of real emotional horror and anguish – and it is then that the movie’s title begins to make sense.

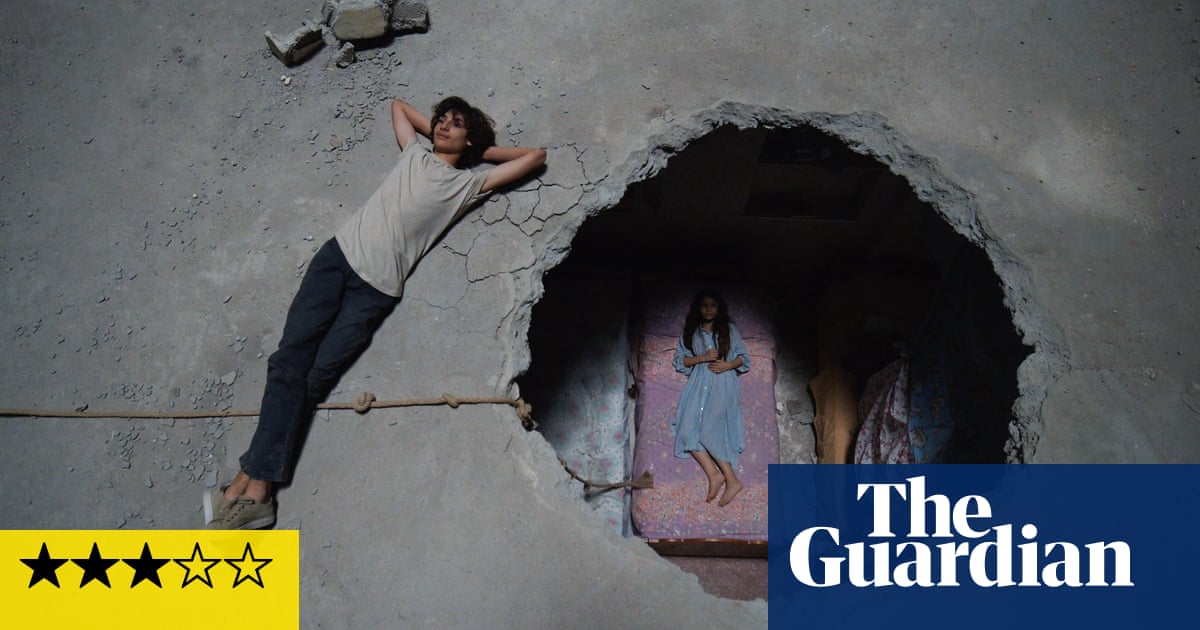

In present day Georgia (that is, the 1980s), we witness the solemn funeral of one Varlam Aravidze (Avtandhil Makharadze), a smalltown mayor and blackshirted party apparatchik whose bullying reign of terror created a legacy of fear which his surviving victims and complicit politicians are trying to convert into a kind of earnest sorrow. The obsequies are attended by his uneasy middle-aged son Abel (also played by Makharadze) and the deceased’s grandson Tornike (Merab Ninidze). But the town is horrified when Aravidze’s corpse is dug up in protest by a local woman called Keti (Zeinab Botsvadze), who leaves the mouldering body posed out in the open like a zombie-waxwork parody of Soviet statuary, an undead reminder of tyranny. The body is reburied but she finds a way to dig it up: the return of the repressed.

This is because Keti remembers as an eight-year-old girl the creepy way Aravidze affected to support her artist father before having him exiled (and killed) for supposed decadent artistic crimes; Aravidze also destroyed the church whose religious frescoes her father admired. The same murderous fate awaited her mother, as well as a local magistrate and the magistrate’s secretary. All this comes in a flashback of Keti’s traumatised childhood, complete with unnerving dream-sequences and hallucinatory interludes which may or may not be waking reality.

As for the unspeakable, puffed-up pomposity of Aravidze – of course he resembles Stalin, and Makharadze actually played Stalin in the 2005 BBC TV adaptation of Robert Harris’s thriller Archangel. But his thin little moustache is like Hitler’s, his paramilitary uniform makes him look like Mussolini and his slick-backed hair makes very much resemble Britain’s very own Oswald Mosley. (But this, I think, is simply because Mosley was trying to look like Mussolini and Hitler.) Aravidze is a comic opera fascist, who fancies himself a bit of an opera singer. But there is nothing funny about the violence that he perpetrates. The tyrant’s grandson Tornike supports Keti and is overwhelmed at his family’s culpability and can find no way of coming to terms with the truth. The surrealism and the swirl of images are partly a strategic ambiguity enabling the film-maker to skirt around the censor. But Abuladze also shows us they are a type of abuse symptom, a way in which the mind reels away from agonising thoughts and memories, converting them into something else.

This superbly made film could be said to have influenced and been itself influenced by Terry Gilliam and Emir Kusturica and might later have found an echo in Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin. It’s a macabre but effective kind of political protest against amnesia.